Emma J Long

Emma J LongThe internal anatomy of a prehistoric creature the size of a poppy seed has been revealed in “astonishing detail”.

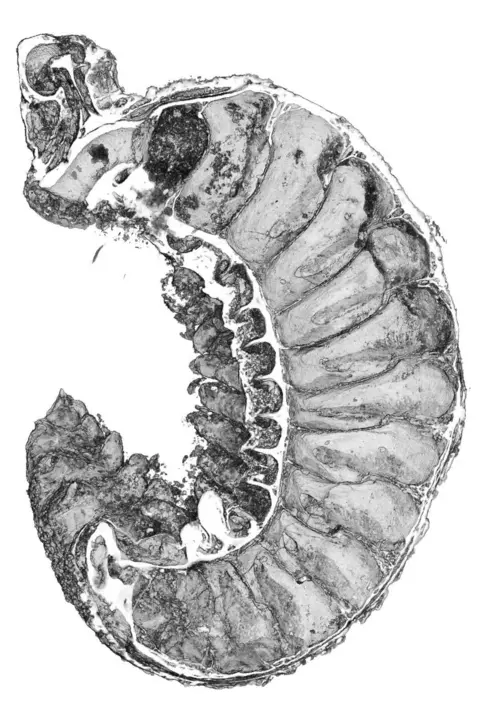

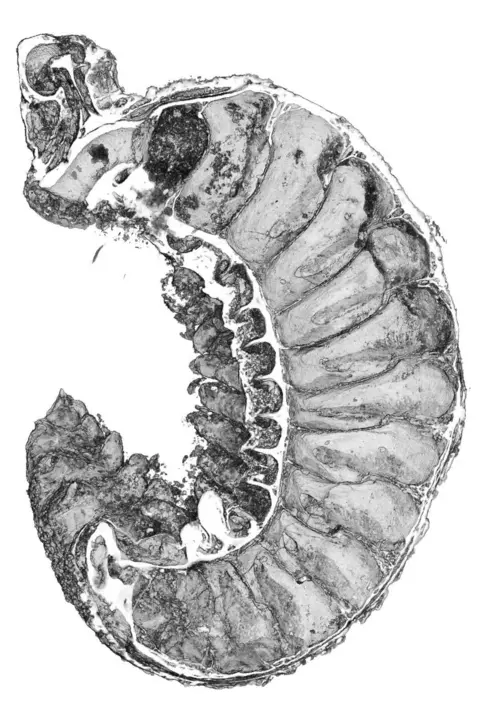

Researchers used powerful X-rays to scan the 520-million-year-old fossil.

The results, published in the journal Nature, reveal its microscopic blood vessels and nervous system.

It is a peek inside the body of one of the earliest ancestors of modern insects, spiders and crabs.

Lead researcher Dr Martin Smith said this was a dream fossil, in part because it was preserved in its larval, or immature, stage – when its body was still developing.

“Looking at these early stages really is the key to understanding how those adult [body shapes] are formed – not just through evolution but through development.

“But larvae are so tiny and fragile, the chances of finding one fossilised are practically zero – or so I thought.”

Dr Smith’s colleagues found the fossil in a pile of “prehistoric grit” during a study of half-billion-year-old rock deposits in the north of China known to contain microscopic fossils.

“Our collaborators in China have large amounts of this stuff, which they dissolve it in acid and these little bits fall out,” Dr Smith said.

A team of technicians at Yunnan University spent years sifting through the material and picking fossils out of the dust.

After examining this particular specimen under the microscope during a trip to China, Dr Smith said, he had realised it was “something very special” and asked if he could bring it back to the UK to have a closer look.

The team mounted the fossil on the head of a pin in order to scan it with intense X-rays at Oxford’s Diamond Light Source facility. That is where its internal secrets were revealed.

“When I saw the amazing structures preserved under its skin, my jaw just dropped,” Dr Smith said.

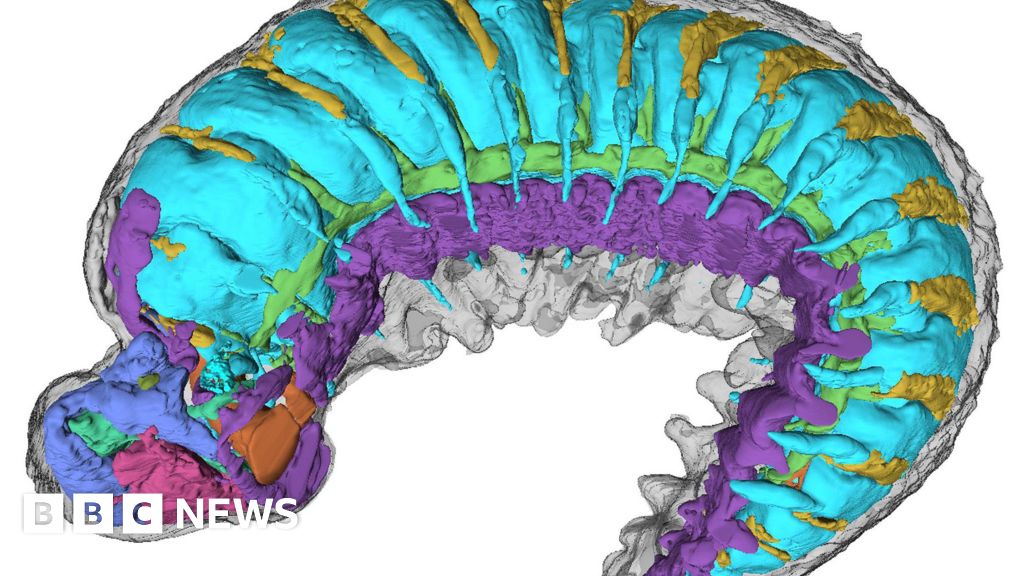

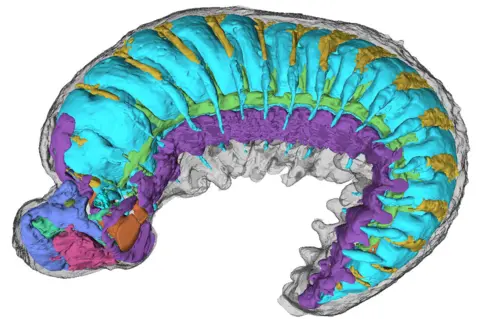

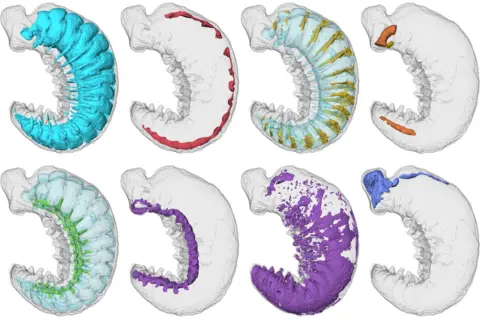

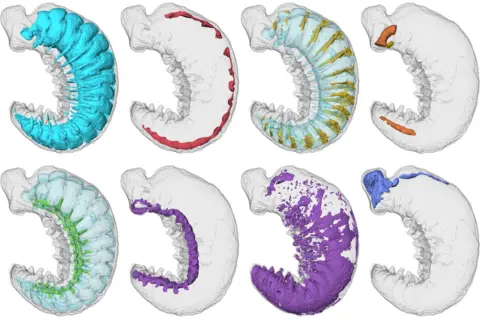

Researchers generated three-dimensional images of miniature brain regions, digestive glands, a primitive circulatory system and even traces of the nerves supplying the larva’s simple legs and eyes.

Its brain cavity, which is divided into segments, has revealed the ancestral “nub” of the specialist, segmented heads of modern insects, spiders and crabs that later evolved their various appendages, such as antennae, mouthparts and eyes.

Study co-author, Dr Katherine Dobson, of the University of Strathclyde, said the natural fossilisation had “achieved almost perfect preservation”.

Dr Smith said this might have been caused by high concentrations of phosphorus in the ocean where this larva briefly lived and died.

“It’s washed into the oceans when rocks erode on land,” he said.

“And that phosphorus seems to have flooded the tissues of our fossil,” essentially crystallising its tiny body.