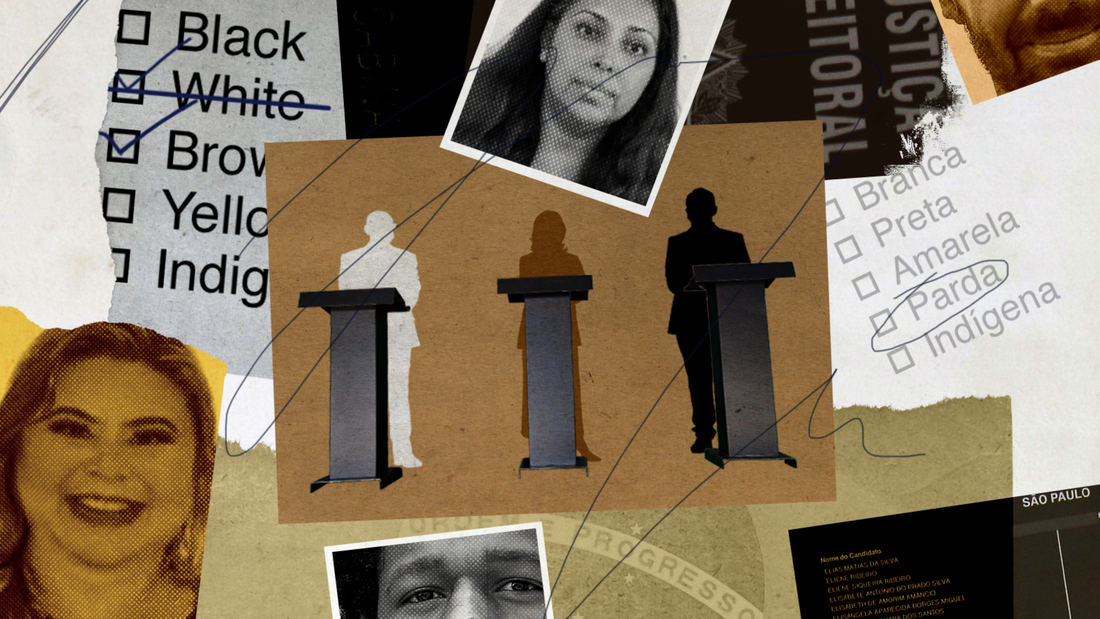

Interviews with several Brazilian candidates revealed a range of reasons for race changes — some said they or campaign officials had simply made a mistake while filling their candidacy form, some said their family background gave them a claim to multiple racial groups, and some said they had recently started to feel a sense of belonging in a new racial category.

Brazilian politicians do “have some latitude to fluctuate on how they present themselves” in order to connect with supporters, Andrew Janusz, a political scientist at the University of Florida who has studied the race changes of candidates extensively, told CNN. Nevertheless, “individuals don’t have total freedom of choice, so if someone is really fair-skinned, they might not be able to say that they are Black, for example,” he said.

Official demographic categories in Brazil have traditionally focused on what demographers call marca — each individual’s external appearance — rather than family origins, unlike the US.

The most common racial change for politicians last year was from White to Black or Brown, a shift made by more than 17,300 candidates. But vast numbers of candidates also moved in the opposite direction: About 14,500 switched from Black or Brown to White — the second-most common change.

Adriana Collares, who ran for city council in Porto Alegre, told CNN that her racial declaration changed only because her previous party had mistakenly described her as White in 2016, against her wishes.

“I never considered myself White, but there was no name for what I was,” she says. “I never felt like I had the right to call myself Black. I was always recognized as ‘tanned,’ as ‘mulatta,’ as anything but Black. Then came this term, ‘Pardo,’ and I found my place in the world.”

“Pardo” translates literally to “Brown,” but can also mean mixed-race. Though not commonly used colloquially among Brazilians, it has been used by national statistics agency IBGE, including in the census, as an official category since the 1950s, and is currently the largest group in Brazil.

Since the 2016 election, Collares left her old party and moved to a new one. In the 2020 election, she again requested to be described as Brown. This time, the party respected her choice.

In contrast, Adriana Guimarães, who ran for city council in Manaus, switched her racial declaration in the opposite direction. She told CNN that she selected Brown in 2016 after being ideologically conditioned by the left.

“In Brazil, we have a mixture of races. In my case, I also have that mixture, of Black, White, and Indigenous. But under Lula and Dilma, there was a push for Brazilians to identify as Brown,” she said, referring to campaigns sponsored by the administrations of former presidents Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff that described Brazil as a mixed-race nation.

After an economic crisis and a corruption scandal hit the country in the early 2010s, Guimarães, like many other Brazilians, began to embrace a more conservative view of the world. She was also reacting to what she perceived as government overreach in the private sphere.

“I started participating in conservative movements,” she says. “I started researching conservatism, reading about Ronald Reagan in the United States and Margaret Thatcher in the United Kingdom, and I ended up noticing that I’m conservative.”

She also noticed her racial identity in a new way. “My race change happened due to my new political ideology,” says Guimarães, now a supporter of President Jair Bolsonaro.

In 2020, she declared herself White.

“I could say that I’m Parda because my grandmother was Black. But my color is White. My color is not Parda. I’m not a ‘neutral burned Yellow.’ I believe that saying that I’m Parda is like saying that I’m neutral. But I have my position, I have my strength, I’m not neutral. It’s the same thing with that neutral gender. It’s like being undecided,” she said.

Picking an identity

Brazil’s official racial categories have evolved over time, and some contemporary efforts to change them are part of a broader push to rectify inequalities rooted in the country’s history.

Slavery lasted longer in Brazil than in other places in the West, and involved more people than in other countries in the Americas — of the 10.7 million slaves who arrived alive on the continent, about 5.8 million were brought to Brazil, compared to about 305,000 taken to the United States, according to the Slave Voyages database.

“Violence has characterized Brazilian history since the earliest days of colonization, marked as they were by the institution of slavery,” write Heloisa Starling and Lilia Schwarcz in their history “Brazil: A Biography.” Even after slavery ended, “its legacy casts a long shadow.” To this day, the country continues to suffer from steep social and racial inequality.

While the nation shows “cultural inclusion” — exemplified in diverse participation in popular traditions like samba, football, and capoeira — they warn that “social exclusion” still means that “the poor, and above all Black people, are the most harshly treated by the justice system, have the shortest life span, the least access to higher education, and to highly qualified jobs.”

That exclusion can be seen in politics too. According to the national statistics agency, Black and Brown people are the majority in Brazil, but in 2018 made up only about 40% of candidates for Congress. The disparity increased even more after the election — only about 25% of successful candidates were Black or Brown, according to the Institute of Socioeconomic Studies, an independent research institute. Brazilian legislators elected in 2018 were overwhelmingly White.

These initiatives became rarer under the right-wing administration of later president Michel Temer and the current far-right administration of Bolsonaro. So progressive politicians have sought to advance social equality by pushing judges to interpret existing legislation, including the constitution, which repudiates racism.

Putting money behind representation in politics

When it comes to funding and advertising, she wrote, proportionality mattered — meaning that if a party has 30% of female candidates, those women should get 30% of the party’s total allocated funds and 30% of its airtime. The new rule was approved in time for the 2018 federal election.

These rules could make a significant difference in driving funds to some candidates from underrepresented groups and even increase their chances of being elected, says Luciana Ramos, a professor of law at Fundação Getúlio Vargas who has tracked the application and impact of the two new parity rules.

Tracking how political parties manage their electoral decisions is relevant in Brazil because most party activities and electoral campaigns are publicly funded. In 2020, Brazilian political parties received a total of R$3 billion ($540 million) from national coffers.

Politicians also get free airtime on television and radio. Last year, that was at least 1h30 per day distributed among parties for about 30 days before the election, according to figures published by the Electoral Justice.

Some politicians are clearly sensitive to the scrutiny. Kelps Lima, who ran for mayor of Natal and declared himself as White in 2016 and Black in 2020, answered a broad question about his race change with a vigorous denial that it had anything to do with funding.

“I declare to be Black since always and I NEVER USED QUOTAS in any moment of my life,” he wrote to CNN. “In 2016, the party made a MISTAKE and declared me as WHITE.” Lima added that he didn’t use campaign funds reserved for Black and Brown candidates and said that he had declared to be Black in two previous elections.

A small portion of politicians who changed race in 2020 had made consistent declarations until that year: CNN’s analysis identified about 360 candidates who declared themselves White for two or three elections, between 2014 and 2018, then changed their race to Black or Brown as the new racial equality rule came into force in 2020.

“I owed this to my origins,” said Marcio Souza, a candidate for city council in Porto Alegre who identified as White in two previous elections before changing to Black. “I’m absolutely a result of miscegenation,” he wrote in an email to CNN. “My mother was White, green eyes, Portuguese and Spanish, and my father was dark brown, dark brown eyes, Portuguese and Black.”

He says he made the change as a conscious statement of solidarity. “For a long time, I have been thinking about this subject,” he wrote. “Due to the occurrences of racial crimes, I decided to adopt, in a positive manner, one of the elements of my racial composition, following my consciousness.”

“From that decision, I didn’t receive financial benefits,” he added. “I’m at peace and I believe to be contributing to the fight against racism.”

Another candidate, Vanderlan Cardoso, who ran for mayor of Goiânia, declared himself White for three consecutive elections, before selecting Brown in 2020.

Cardoso did not answer requests for comment from CNN that mentioned his 2014 and 2016 racial declarations.

He lost the election and returned to his job in Brasília as a senator representing the state of Goiás. But the electoral data shows that tens of other candidates who made the same move from White to Black or Brown ended up winning their races, including mayors of state capitals.

Verifying racial claims

Could Brazil’s racial fluidity end up weakening affirmative action rules designed to bolster under-represented groups, when those rules depend on stable racial categories to work?

“Most everyone will say that racial inequality is a major issue in Brazil, and that things need to be done to ameliorate inequality,” says Janusz, the political scientist who studies the race changes. “But to do that, you have to identify some boundaries, some procedures to identify beneficiaries.”

In other affirmative action systems in Brazil, commissions exist to check if people are telling the truth.

When Collares, the city council candidate from Porto Alegre, made use of the affirmative action programs approved under Lula and Dilma and took advantage of a racial quota to get her current job as a civil servant, she had to go through an interview with a commission that checked if she was really Brown.

“I believe they wanted to know if I had experienced life as a non-White person,” she says. “I had to do an interview. I had to bring family photographs, childhood photographs. They asked about my family life, the culture inside our house, family habits. I spoke a bit about my life. I thought it was kind of surreal, but fine.”

But political parties are not required to verify candidates’ racial declarations, and multiple parties that spoke to CNN said they were unaware that their politicians had changed race.

Both PT, the left-wing party of former presidents Lula and Dilma, and PSDB, the right-wing party of former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso, said that they had not recorded race changes among their candidates, even though the electoral data reveals thousands of changes in each party.

Some parties benefitted candidates who had recently switched races. A list of Black and Brown candidates who received more funds due to the new rule sent to CNN by PSDB included one politician who had run for office as White in 2018 and as Brown in 2020. The party did not answer a question about that specific candidate.

Gabriela Cruz, the leader of the Black wing of the PSDB party, told CNN she believed there might have been fraud in the 2020 election. “I observed cases in which the self-declared person was White,” she said, but added that making any further claims was complicated. “I don’t have enough evidence to say if it was only to access funds or if it was a question of racial awareness.”

Cruz thinks parties should be required to check candidates’ physical traits against their racial declarations, “with the support of the Black wing of the party.”

Though she respects people’s self-identification, she argues that physical traits matter. “Racism in Brazil is practiced through social constructions that exclude people by function of their physical characteristics, like skin color, facial features, and hair texture,” she says. “That is what places people in their racial group, and not their genetic composition.”

Ramos, the law professor studying the funding rules, says that there could have been instances of deceit in 2020, but noted that fraud could also take other forms. “A party leader could direct campaign resources to a Black candidate and order her to transfer those resources to a White candidate, for instance,” she said.

The Superior Electoral Court told CNN that it has not received any reports of fraud from the 2020 vote so far, in part because parties are still making their campaign budgets public. It said that potential punishments would include forcing a candidate to return the funds used in the campaign and, in more serious cases, removing them from office.

Brazil is changing

Population data from the national statistics agency shows that the share of Brazilians declaring to be Black and Brown increased during the 2010s, and that now represent about 56% of the entire population. Meanwhile, the share of Brazilians declaring to be White fell — they now make up 43%. Only recently have Brazilians had the option to declare their own racial identity — historically, census interviewers assigned their subjects a racial category.

But Brazil’s political arena is failing to reflect the country’s diversity, despite the new equality rules approved in 2018 and 2020. Ramos, the law professor, points to a preliminary tally by 72 Horas, a watchdog group, that shows that, based on the budgets that have been made public so far, parties failed to distribute support proportionally, either by race or gender.

Closing the gap between genders and races is important if Brazil wants to create better policies for specific groups, says Collares, the city council candidate from Porto Alegre.

She believes that when a politician belongs to a certain group, their work is informed by the life experience of being a member of that group. “If you don’t experience it in your life, if you don’t feel it on your skin, it’s difficult to understand, it’s difficult to prioritize,” she says. “A man thinking policies for women is different from a woman thinking policies for women.”

“We need to try to reach this parity, this representation,” she adds. “The majority of our people are Black and Brown, and we don’t see that.”