The component items in such phrases are not contradictory. But by deeming the entire term as an oxymoron, a contradiction within the components is insinuated, amplifying the comic or cynical effect.

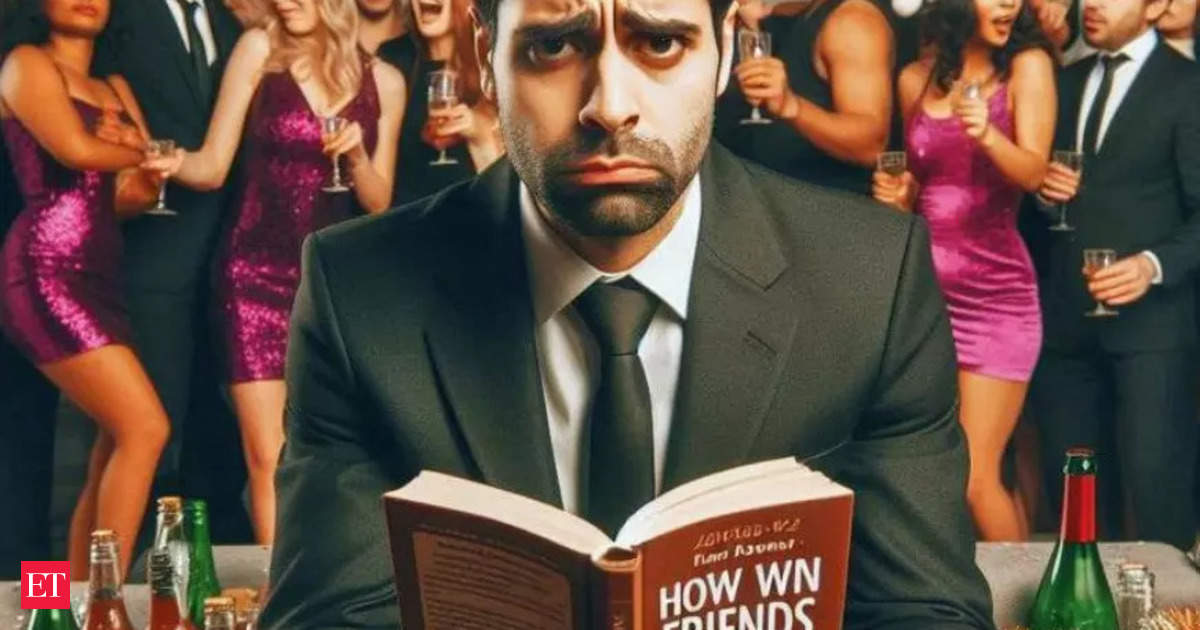

‘Self-help book’ belongs to both categories. There is a logical contradiction because if the basis for changing oneself is internal motivation, then can a manual help? And, by terming it an oxymoron, any suspected contradiction is imposed on it and comically exaggerated.

The self-help genre, replete with contradictions, is a huge hit. It goes beyond books into podcasts, seminars, and courses. Adding to the morass, self-improvement is a nebulous concept not easily measured by objective metrics. This vacuum makes the area a thriving ground for smooth talkers and glib communicators.

A typical book is based either on the author’s struggle and breakthrough into success, or on the distillation of common characteristics of successful individuals. This formula suffers from these key logical flaws and contradictions:

That the book can help all. Just because something worked for one individual does not make it automatically appropriate for many. The content in some books acknowledges this paradox and exhorts to ‘find our own path’. Yet, the book titles and chapter headers do not headline this aspect. Many books lay out a stepwise plan to some desired state that starts with a first step or change. It could be ‘face your fears,’ or ‘imagine a successful you’. This could be a baby step for some, a giant leap for others depending on individual personalities. So, some will remain stuck at this first step. Books that promise an outcome such as ‘Get Rich,’ or ‘Achieve Success,’ only on the basis of one’s own actions are making false claims. One’s actions are only one component of any desired outcome. Any person of above-average achievements and with reasonable self-awareness will point to luck and the help of others as contributing to his or her success. One’s own actions play a vital role, but are insufficient. Books that promote process or habit changes – rather than specific outcomes – do not suffer this contradiction (but are still subject to the above caveats).

Deriving a formula from one person’s experience or from the common habits of successful people overlooks individuals who may already be following these habits but have not achieved success. Dropping out of college, for instance, is a trait common to celebrated business titans like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates. But it would be wrong to conclude that dropping out will lead to business success. Many who have dropped out did not make it. And there are many who did not drop out and succeeded.

But there are valuable self-help books. Books that focus on specific skill development such as learning an instrument, or on a skill such as painting, or on some technical concept can obviate the need for significant in-person instruction – although some ‘traditional’ instruction can accelerate learning.

Most of the books that focus on ‘vague’ traits, market themselves by promising a path to some exceptional state. Even accounting for the above contradictions, one basic conflict is that, by definition, only a few can reach exceptional status. Should one still aspire and dream? Try to improve oneself? Does this confirm the oxymoronic status of ‘self-help books’?

Acceptance of this tension is important – that inspiration and instruction drawn from a book, or from an individual’s story, may not help us reach the desired summit state. Instead, there is inherent satisfaction in the journey towards a better version of the self. This acceptance is an important step – probably, the first step. And there is no self-help book that can teach it.

The writer is managing director, Resonance Laboratories, Bengaluru