One instance was after the screening of Don Palathara’s Family, a quietly observant, slow-burn film about a Keralite Christian community being infected (in ways not always spelt out) by the presence of a seemingly helpful young man.

Much of this narrative is organised around images of priests, nuns, or rituals that maintain a grip over ‘regular’ people. An undercurrent is that religion can bind groups in conspiracies of silence, keeping unsavoury things hidden.

Were you concerned about offending religious sensibilities when you made this film, a viewer asked Palathara afterwards. ‘No, I wasn’t concerned about that at all,’ he replied evenly, ‘When I was growing up, no one worried that they might be offending my feelings by imposing religion on me.’

This response begat applause, and the audience seemed to be on the side of the film’s view of organised religion. But a slightly more abrasive mood followed the screening of Siddharth Chauhan’s debut feature Amar Colony, a drolly funny film about another community – the residents of a Shimla building, including a pregnant woman who sometimes has romantic fantasies involving a young garbage collector. After the show, two or three agitated people demanded to know why the director had shown ‘disrespect’ to Hindu gods and devotees (mainly Krishna and Meera) by associating their names with characters who indulged in sexual peccadilloes. They also objected to what they saw as insensitive religious imagery.

What had briefly threatened to turn into an outroar soon died down. But there was something notable about the insistent, bullying tone. All of us can get offended by different things (including, as Palathara implied, by the hegemony of religion and the way children are subjected to it from an early age).But these viewers weren’t just voicing hurt. They were behaving like they were entitled to get a clear explanation from the filmmaker.They were also ignoring the more positive religious imagery elsewhere in the film, such as an old woman, a Hanuman devotee, imagining a mace as her weapon of choice when she has to deal with trouble.

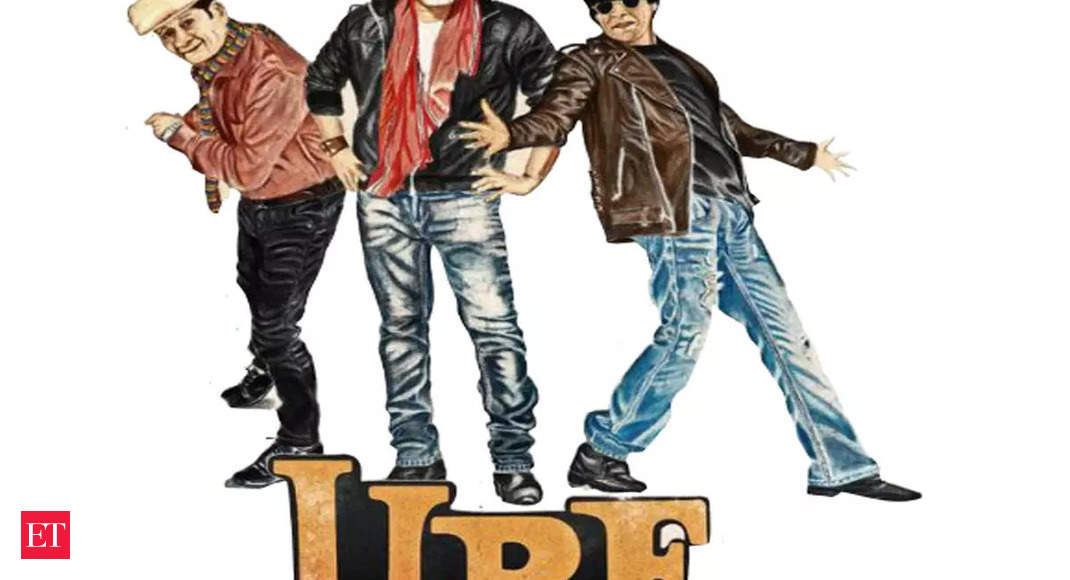

The most enjoyable film I saw at the festival, though, dealt with another type of relationship between gods and devotees. Geetika Narang Abbasi’s lovely, empathetic documentary, Urf, is about movie-star ‘duplicates’, focusing on three men – Firoz Khan, Kishor Bhanushali and Prashant Walde – who made a name and a living by impersonating Amitabh Bachchan, Dev Anand and Shah Rukh Khan, respectively, in low-budget films and in live shows.

But after years of doing this, they also yearned to find an independent identity for themselves. Or at least to not forever walk in the shadows of giants.

As a youngster, when I watched films or TV skits featuring celebrity imitators, I felt uneasy. As a Bachchan bhakt, or as someone who had admired the black-and-white-era Dev Anand from a distance, I may even have been offended. Mimicry of these screen gods – often done to get facile laughs – seemed in poor taste.

Abbasi’s film made me rethink my feelings by depicting the real-life struggles of these doubles, and by letting their own distinct personalities slowly emerge from beneath the masks – though the film does also derive some charming humour from their impersonations.

After the screening, when Firoz Khan appeared from the audience, announcing his presence by delivering a line in the Bachchan baritone, everyone applauded. But by the time he was on stage, answering questions about his life and career independently of being a duplicate, it was possible to see him as a star in his own right. Urf had reclaimed the dignity of people like him, liberating them from their gods.