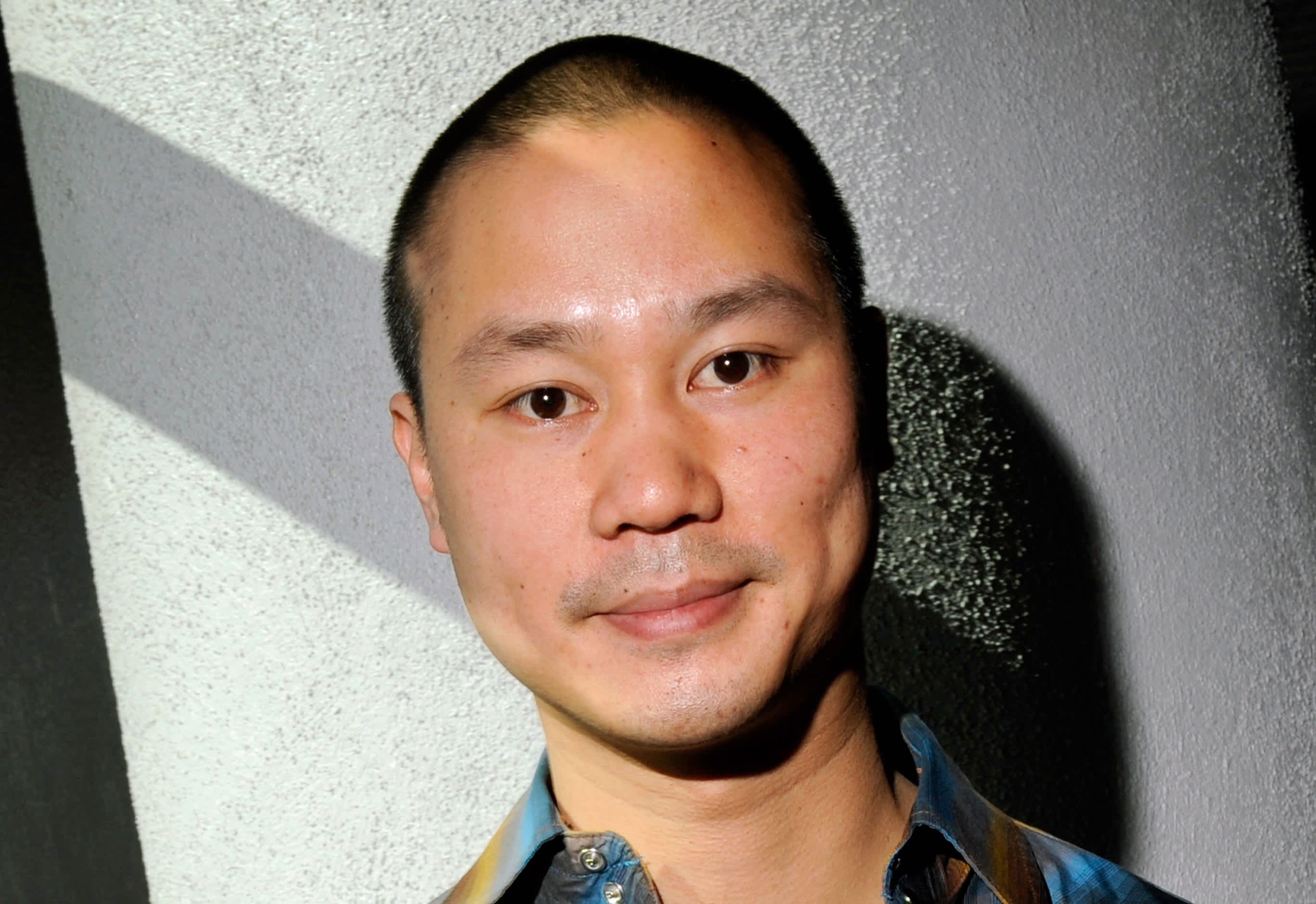

Tony Hsieh, CEO of Zappos.com

Getty Images

Tony Hsieh seemed to have it all.

Hsieh launched the Las Vegas-based shoe ecommerce platform Zappos and sold it to Amazon for $1.2 billion in 2009 — the largest acquisition in Amazon’s history at the time. He was an entrepreneur darling for his unconventional leadership style, which put culture above all else, and scoffed at corporate hierarchy. In 2010, he published a book codifying his own leadership style in a book, “Delivering Happiness: A Path to Profits, Passion, and Purpose.” He had also become an known for donating $350 million to revitalize downtown Las Vegas.

In a first-person tell-all piece Hsieh wrote and published in business magazine Inc in 2010, Hsieh describes flying to Seattle to meet with Bezos before the deal had been formalized.

“I gave him my standard presentation on Zappos, which is mostly about our culture. Toward the end of the presentation, I started talking about the science of happiness — and how we try to use it to serve our customers and employees better,” Hsieh wrote.

He continued: “Out of nowhere, Jeff said, ‘Did you know that people are very bad at predicting what will make them happy?’ Those were the exact words on my next slide. I put it up and said, ‘Yes, but apparently you are very good at predicting PowerPoint slides.'”

The moment now reads like a harbinger of hard times to come.

On Nov. 27, Hsieh died from complications of smoke inhalation at the age of 46, after being rescued from a fire in a small storage area behind an beachfront home in New London, Conn. Officially, the death was ruled an accident by the Connecticut Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. At least one emergency worker was reportedly overheard saying he’d barricaded himself inside.

The years leading up to Hsieh’s untimely death included voracious alcohol and drug use, extreme “biohacking” which included seeing how long he could go without eating and urinating, an obsession with fire and candles, and buying houses in Park City, Utah, and paying people double their highest dream salary to come and live on the properties Hsieh bought if they would be happy with him, according to reports in Forbes and the Wall Street Journal.

Even without knowing what exactly happened in that shed in Connecticut, Hsieh was clearly in anguish. Mental health experts caution that the ongoing Covid pandemic can increase feelings of isolation and loneliness, and offer tips and resources to seek help for yourself or loved ones.

Loneliness is not just about proximity

The absence of people physically nearby does not define loneliness, says C. Vaile Wright, the Senior Director of Health Care Innovation in the Practice Directorate at the American Psychological Association.

“Loneliness is really this perceived sense of not having somebody who cares about you. That’s different than just being alone. People can be alone and not feel lonely,” Wright tells CNBC.

“A lot of us are physically isolated as a result of Covid, but it’s still really critically important to maintain social connections that are meaningful and counteract that sense of loneliness.” That can mean phone calls, video calls and outdoor walks with friends, but it can also mean sending care packages or writing letters, Wright says.

If a friend or loved one is isolating, that’s a “really critical red flag,” says Wright.

“The hallmark would be when somebody’s symptoms are interfering with their ability to function in some significant ways,” Wright tells CNBC. “They’re not able to work, even work from home, or to attend school. They stopped taking care of themselves, which can look like not showering, not eating, not sleeping or they are unable to take care of loved ones.”

In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, where staying away from other people has become the norm to stay physically healthy, isolation can manifest as a person not showing up for regularly scheduled virtual appointments, not returning texts in accordance with their usual cadence or abusing substances.

It is harder to identify dangerous loneliness when everyone is being asked to stay apart, says Wright.

“It becomes even more important for us to do what we can to try to reach out to people, typically those that we know might be more vulnerable, and to be persistent,” she tells CNBC. Sometimes, concerned friends and loved ones don’t reach out because they don’t know how to fix the situation, Wright says, but even just expressing concern can be a huge help.

“Usually people are just looking for somebody who cares about them, who wants to hear what they’re going through, and validate their experience and then maybe help problem-solve,” Wright says. “But really I think we just need to be reaching out and asking open-ended non-judgmental questions about how people are doing.”

Good, simple options for what to say if you are concerned a friend or loved one is in danger are as follows, according to Wright: “I’m worried about you. Can you tell me how you’re doing?” Or, “I’ve noticed that you haven’t you know then returning texts and I’m wondering if you’re OK.” Letting someone who is feeling lonely that you are there for them is key, she says.

Why loneliness is bad for our health

“Scientists from various disciplines argue that that humans are our social species, and so throughout human history we have needed to rely on others,” Julianne Holt-Lunstad, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Brigham Young University tells CNBC. “And so being part of a group has been associated with with safety and efficiency of effort. And so being outside of a group or alone is very threatening.”

Social isolation means having to “cope and deal with everything entirely on our own,” said Hold-Lunstad. “It has been argued that our brains in essence has have evolved to expect the proximity to others and so when we don’t, when we lack this proximity to others — and particularly trusted others — that this creates a state of alert and threat in our brain.”

When the brain is in a “heightened state of alert,” it sends signals to the human body to be also and that “can include things like heightened blood pressure and heart rate, circulating stress hormones, and inflammation,” she says. “This information in turn has been linked to a number of of chronic illnesses — it’s been linked to depression, and interestingly even linked to greater susceptibility to viruses.”

Hold-Lunstad’s research has shown that the perception of support is enough “dampen these physiological responses” associated with feeling isolated. Her laboratory research shows mitigated responses to stress even when the people who give study participants a feeling of support are not in the room.

“So that perception of availability of support is huge,” Hold-Lunstad says. “In one of my studies that we had data from over 300,000 participants globally, we found that perceptions of support were associated with a 35% increase odds of survival.”

Doing kind things for others helps, too. Hold-Lunstad just completed a study between July and September with just over 4,200 trial participants between the U.S., UK, and Australia. It showed that those who completed random acts of kindness for neighbors, whether mowing a lawn or sharing information on where they found baking yeast was available, “showed significant reductions in loneliness over the four weeks.”

Teens and young adults are struggling, too

According to the 2020 American Psychological Associations Stress in America survey, 67% of Gen Z adults (ages 18-23) say that the coronavirus makes “planning for their future feel impossible,” a statistic which psychologist Dr. Mary Alvord highlighted for CNBC. And half of Gen Z teens (ages 13-17) say the pandemic has “severely disrupted their plans for the future,” according to the report.

And while the coronavirus and resulting life changes are a massive hurdle, there are other stressors too, Alvord says, including “racial unrest, misinformation, divisiveness in the population and families, financial stress of families, grief and loss not only from COVID deaths and illnesses, but also from jobs and businesses lost.” There’s also the constant uncertainty around school and whether it will be in person, online or some combination of both, says Alvord.

“Rites of passage are missed,” Alvord said. “Athletic, theater and club activities are missed or held virtually, but not equivalently to in-person.”

“While they are old enough to read and hear the news, they are not always able to keep perspective on all the events and issues,” said Alvord, who is also the co-author of “Conquer Negative Thinking for Teens: A Workbook to Break the Nine Thought Habits That Are Holding You Back.” “When you hear ‘catastrophizing’ such as ‘What if this happens,’ and ‘What if I can’t x,’ this may mean that anxiety is taking over and perspective is reduced. Ask the teen or young adult, ‘What are the realistic chances of something really bad happening,’ ‘Can they handle it,’ and, ‘What would they tell a friend worrying about the same thoughts.'”

Similar to the aforementioned warning signs for adults, “sudden changes in behavior, sleep, eating patterns or shift or cut-off from friends and family, and negative self statements” are key warning signs that young adults aren’t managing, Alvord says.

Parents “can model coping,” Alvord tells CNBC, giving teens and young adults a template to follow for how to handle stress. They can do that by staying calm in the face of stress and unplanned roadblocks. Or, “if they are not calm, they can say something like, ‘I am so frustrated because x just happened. But, I will take a few deep breaths, calm myself, and figure out next steps. I am going to think about 3 things I can do about this situation,'” Alvord says. “‘I can’t control all that is going on, but I can control this part of it and I am thinking of a plan to handle it.'”

Professional resources

If someone you know is in desperate danger, call 911 and send a health professional to their home, says Wright.

Another important resource is the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

If a friend or loved one seems at risk of harming themselves, it’s okay to be direct, says Elinore F. McCance-Katz, the Assistant Secretary for Health and Human Services for Mental Health and Substance Use, the agency within the federal government’s Department of Health and Human Services working to improve behavioral health, which funds the hotline. Tell them they can call the hotline 24 hours a day, she says.

“In a straightforward and supportive way, share what you are noticing and offer to talk about it (e.g., ‘You have seemed very sad, the past few weeks’),” McCance-Katz tells CNBC by way of a department spokesperson. “Be willing to gently ask the direct question: ‘Have you been having thoughts about harming yourself?’ You won’t be putting the idea in your loved one’s head; rather, many see this as a way to open the door for the conversation. It takes away the stigma associated with thoughts of suicide and the shame one may feel if they have them.”

If you are concerned about a friend or loved one and need urgent help or guidance, you, too can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, McCance-Katz says.

If a loved one or friend is showing signs of a deterioration in mental health, professional therapy may be necessary. “Most therapists have pivoted to tele-health, that is video conferencing or phone only, and we know that both of those methods are as effective as face-to-face [therapy],” Wright tells CNBC. The search for a therapist can start with your primary care doctor or your insurance company. If you don’t have a primary care doctor or insurance, you can start by asking friends and family for their recommendations or search on a therapist locator on the web, such as the one at Psychology Today.

Fundamentally, trying to help someone who is struggling with mental health problems is hard. “It can be challenging when you’re the loved one or the friend because there often isn’t a lot in your control other than to reach out, to offer resources, to off yourself as resource,” Wright tells CNBC. “To a certain extent it has to be the person themselves who reaches out. And that’s what’s really challenging.”

Correction: Tony Hsieh passed away on Nov. 27. A previous version of this story gave an incorrect date.