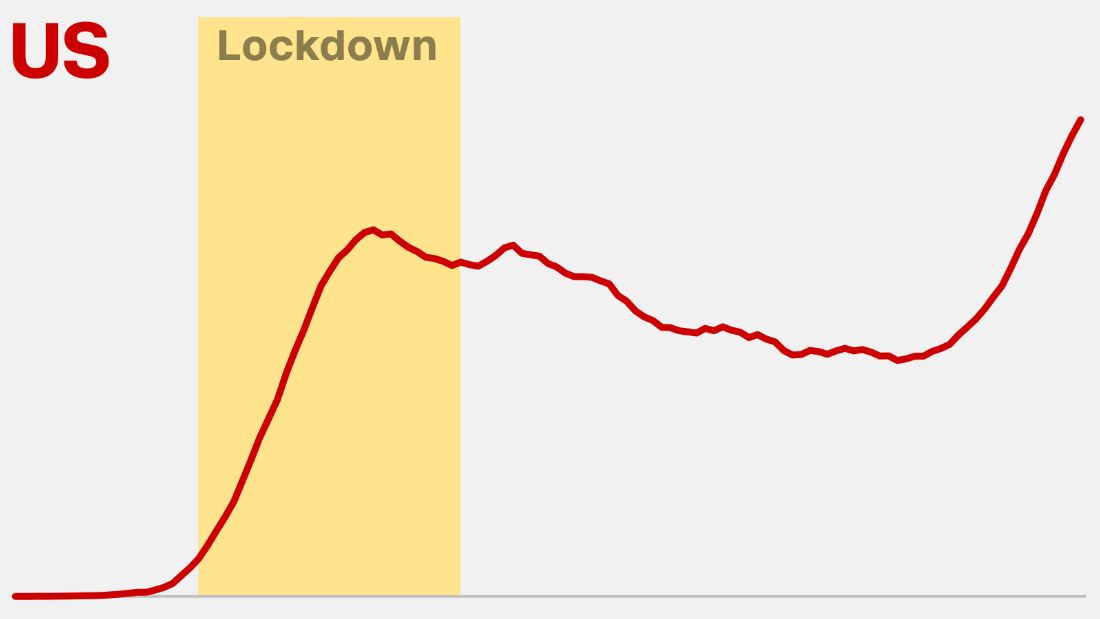

In contrast, three of the four countries with the world’s highest death tolls and case counts — the United States, Brazil and India — have either never properly shut down or started reopening before their case counts begun to drop.

The EU formally agreed a set of recommendations of 15 countries it considers safe enough to allow their residents to travel into its territory on Tuesday. To get on the list, countries have to check a number of boxes: their new cases per 100,000 citizens over the previous 14 days must be similar to or below that of the EU, and they must have a stable or decreasing trend of new cases over this period in comparison to the previous 14 days.

The bloc will also consider what measures countries are taking, such as contact tracing, and how reliable each nation’s data is.

The list includes Algeria, Australia, Canada, Georgia, Japan, Montenegro, Morocco, New Zealand, Rwanda, Serbia, South Korea, Thailand, Tunisia, Uruguay. China, where the virus originated, is also on the list, but the EU will only offer China entry on the condition of reciprocal arrangements.

“I don’t think any human endeavor has ever saved so many lives in such a short period of time. There have been huge personal costs to staying home and canceling events, but the data show that each day made a profound difference,” said the study’s lead author, Solomon Hsiang, a professor and director of the Global Policy Laboratory at the University of California, Berkeley.

Just how successful a lockdown has been depends on a number of reasons, including whether it was put in place early enough. No two lockdowns are alike, so while people in countries like Italy or Spain faced fines if they ventured outside their homes for anything other than essential reasons, in Japan, staying at home was a recommendation rather than an order.

Australia, Canada, New Zealand were quick to restrict travel, while in other countries including Algeria, Georgia and Morocco, kids were the first to see the impact of the pandemic as schools shut.

Other measures included stay-at-home orders, non-essential store closures, quarantining and isolation. Some countries, like Algeria, Rwanda, Montenegro and China have seen outbreaks after restrictions were lifted. That prompted officials to reintroduce some measures locally.

In China, the capital city of Beijing was put under a partial lockdown last month following new cluster linked to a food market. Montenegro brought back bans on mass events last week after seeing a new outbreak of cases following a three weeks of being virus-free. And in Rwanda, health authorities placed a number of villages into renewed lockdown last week after new cases emerged there.

But the restrictions launched to counteract the disease have also been hugely damaging for the economy and have exacerbated existing inequalities in education and the workplace, as well as between genders, races and socio-economic backgrounds.

As shops and schools shut and nearly all travel ceased, hundreds of millions of people around the world have suddenly found themselves unemployed. The impact on the economy is one of the reasons why some leaders, including the US President Donald Trump, have been pushing for swift reopening, even as infectious diseases experts warned about lifting restrictions too early.

A previous version of this story incorrectly stated the number of lives scientists say were saved because of lockdowns. It has been corrected.

Aleesha Khaliq, Dario Klein, Shasta Darlington, Rodrigo Pedroso, Manveena Suri, Paula Newton, Yoko Wakatsuki, Milena Veselinovic and Kocha Olarn contributed reporting.