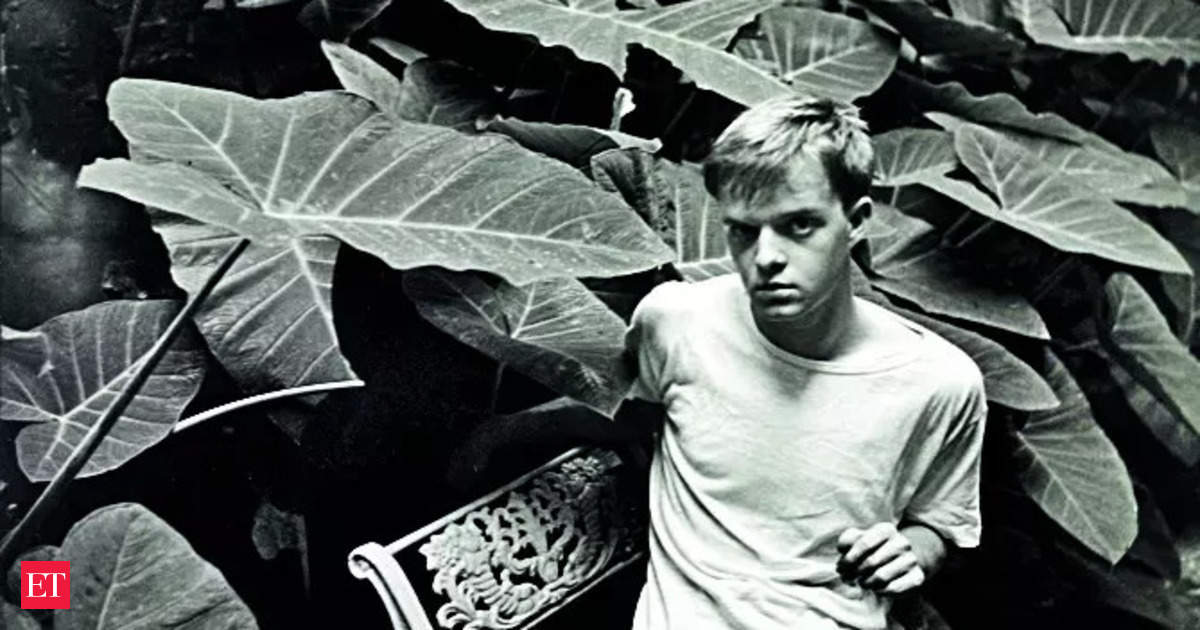

But Capote is still better, because he was self-taught. Born dirt poor in the American South, he was raised by two maiden aunts in Alabama and had one close friend in childhood, Harper Lee, who too would grow up to be a prominent novelist. In Lee’s 1960 classic, To Kill a Mockingbird, Capote appears as the character, Dill.

In the late 50s and early 60s, when Capote was writing In Cold Blood, Lee offered to be his research assistant and minder when they were in Kansas following the Clutter family murder trials on which the book is based. The 2005 movie Capote, with the late Philip Seymour Hoffman in the eponymous role, captures the relationship wonderfully. While Capote never fully acknowledged Lee’s role in the book, many of her observations about town folk, their routines and prejudices made In Cold Blood the true crime classic it is.

My first encounter with Capote was when I bought a copy of his 1958 novel, Breakfast at Tiffany’s at Delhi University. I had seen the 1961 Blake Edwards movie, and while Audrey Hepburn’s gamine charm and Henry Mancini’s sharp score did make an impression on me, I thought the movie was too bland and too rose-coloured. I also felt it needed an edgier leading man than George Peppard.

The novel was witty and dark and had a tremendous narrative pace. I read it twice in a day and marvelled at the depth of Capote’s talent and skill. Later, I would read In Cold Blood and watch the 1935 film Beat the Devil, whose screenplay he wrote with its director John Huston.

In Cold Blood made Capote one of the richest literary writers in America, and a media star who spent most evenings pontificating on some topic on TV stations. As he moved into rarefied social circles, where he was treated as the house jester for his provocative statements and outre behaviour, Capote stopped being the brilliant writer he was for most of his 20s and 30s. Alcohol and cocaine overpowered his talent for most of his remaining life.In the new FX miniseries, Feud: Truman Capote vs The Swans, Capote’s frightening decline is chronicled as his beloved group of NY high society ‘swans’ – Babe Paley, CZ Guest, Slim Keith and Lee Radziwill – cut him off socially when he published an excerpt from his work-in-progress, Answered Prayers, in Esquire. The story is the perfect roman-a-clef: gossipy, sharp and with a tremendous narrative jump. It hoists the New York high society on its own petard. For this betrayal, Capote was cancelled from all the stately homes and yachts he loved cavorting in.

He died a bitter man at 59 in 1984. While Feud is gorgeously shot, and the actors are wonderful – especially Tom Hollander as Capote and Diane Lane as Slim Keith – it makes an error in not emphasising the writing woes Capote was going through. By the end of his life, his advance for Answered Prayers had run into over $1 mn, and he was under pressure to complete the novel.

At various times, he would declare to his publishers he was finishing it. Then, several years passed, editors changed, and he wrangled a new advance from the incumbent editor. No one wanted to lose Capote, least of all Random House.

This pressure, apart from his shunning by the Swans, led to the decline of this all-American Proust. I have never understood how Capote could have been so traumatised to have been banished from high society. For most novelists, that would have been a boon.

After his death, Random House searched for the elusive Answered Prayers manuscript, but only found the three chapters published in Esquire. Random House chose to publish it in 1986 and recover its advance. Even in its truncated form, Answered Prayers is a masterpiece of narrative storytelling. Do read it.