In literature and art, Earth, nation and region have been imagined as feminine. The

Suktam of the Atharva Veda addresses Earth as she who bears the universe (vishvam-bhara) and is a golden-breasted (hiranya-vaksha) nurturer. Three millennia later, the nation was imaged as Bharat Mata in modern Indian art, her iconography made famous by Abanindranath Tagore’s 1905 painting.

The personified identity of Earth or land is not restricted to the mother, but is also perceived as consort or paramour. In Hindu mythology, Vishnu in his boar incarnation (Varaha) rescued Earth goddess Bhu-Devi from the depths of the ocean. She, along with Sri-Devi, is the god’s consort. In ancient and medieval India, kings are addressed as bhu-pati (lord of Earth) in epigraphs, and the iconography of Varaha-Vishnu in art also serves as a political metaphor for the king as bhu-pati.

In Valmiki’s Ramayana, Ravana’s Lanka is described as a desirable maiden loved by him. In pre-modern India, royal charters described a king’s power and authority over land in the sensual, gendered language of dalliance and bodily claims over a woman, as historians have earlier discussed. The Chola king Vijayalaya’s capture of the city of Tanjore is couched in poetic metaphors of the well-endowed city as his beloved wife, whose hand he seized for the sport of love.

The conquest of an enemy king’s territory is expressed in gendered terms in a 9th century charter of Rashtrakuta king Amoghavarsha that eulogises the capture of the Chalukya kingdom by a predecessor. The battlefield is described there as a place of ‘choice-marriage’ from where the victorious king forcibly wrested away the fortune (Lakshmi) of the Chalukyas.

Abduction as a motif in Indian sculpture has had an early and wide currency. A few terracottas from the Gangetic valley belt belonging to the post-Maurya period (c. 2nd century BCE to 2nd century CE) portray a gigantic figure abducting a woman. In one such plaque from Kausambi, the woman’s jewels lie scattered on the ground, a folkloric motif reminiscent of Sita’s abduction by Ravana in the Ramayana. Sita is herself deeply associated with Earth, in whose furrow she was discovered and into whose womb she finally disappeared. Her abduction by Ravana and rescue by Rama in epic mythology are symbolic of the forcible capture and ultimate victory of good over evil.

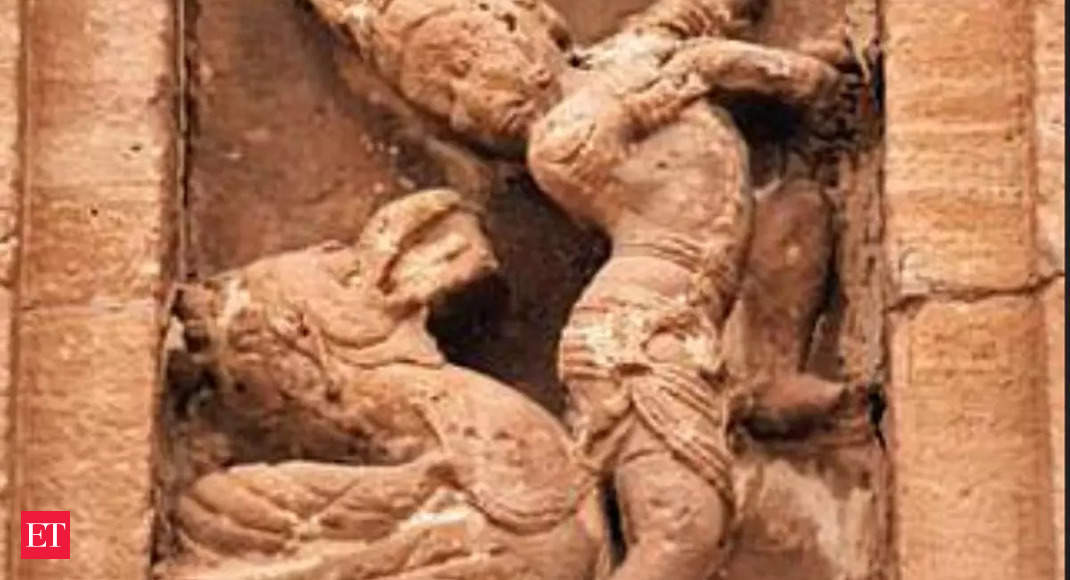

A charged portrayal of Sita’s abduction by Ravana and the ensuing fight with the great vulture Jatayu graces the outer wall of the 8th century Virupaksha temple at Pattadakal in Karnataka (see photo). The animated rhythm of this masterpiece reveals Ravana’s right foot in Jatayu’s clutches, his torso turned towards Jatayu, and his hand pulling out the sword to attack. The artist brings the charged faces of Ravana and Jatayu extremely close, their combative glances locked fiercely, each directly challenging the adversary.

A little above, Ravana whisks away Sita in his magical chariot. Over the niche, Sita’s visage peeps from the half-opened door of her cottage carved as a Dravida temple, leading the viewer’s mind to the complex cause-effect relationships of the encounter. The bottom panel captures the vulture-king’s momentary triumph when he injured and delayed the demon-king.

Today, we are gender-sensitised to the cosmetic use of politically correct rhetoric in formal expressions. But power equations relating to the abuse of territory and women continue unabated. The spectre of abduction of nature and nurture, and of violence against women, for greed, power, and territorial control have far more disastrous consequences in an altered international order.