A century ago, O.W. Gurley built an empire of African American businesses in Tulsa. Though it all came burning down in the massacre of 1921, new generations of entrepreneurs rose from the ashes.

Ottowa W. Gurley knew he would never be a success in the Jim Crow South. Born on Christmas Day 1868 to freed slaves in Huntsville, Alabama, he grew up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas where he was largely self-educated. Gurley married his childhood sweetheart, Emma, became a teacher, and then took a relatively cushy job with the U.S. Postal Service—but he dreamed of a better life in America. Along with his new bride, Gurley risked everything to join a stampede of homesteaders seeking freedom, opportunity and wealth in the Great Oklahoma Land Rush.

On September 16, 1893, the 25-year-old entrepreneur joined the Cherokee Outlet Opening, running fifty miles before finally stopping at a plot of prairie grass. Standing on a plot of land with Emma, the staked a claim in what would soon become Perry, Oklahoma, one of many towns advertised to Blacks in the new territory.

Gurley envisioned Oklahoma as the start of a new life for Black Americans decades after emancipation—and he was ambitious. He ran for county treasurer, was made principal at the town’s school, and ultimately opened a successful general store, which he ran for a decade. By the turn of the century, Gurley and his fellow homesteaders heard tales of giant oil fields in the nearby boomtown of Tulsa. A gusher well called the Ida Glenn Number 1, the first find in the massive Mid-Continent Oil Field, was making local Tulsans rich—and eventually turned no-name wildcatters Harry Ford Sinclair and J. Paul Getty into oil barons.

O.W. Gurley wanted in.

He sold his store and land in Perry and moved about 80 miles to Tulsa in 1905, taking the second major risk of his young life. He bought a large tract of land on the north side of the Frisco train tracks. On a barren plot, he started to map out a city for upwardly mobile Blacks, who, much like himself, were looking for opportunity. After emancipation, Blacks who had followed the Native American “Trail of Tears” as slaves, could now claim 40 acres of land. They migrated westward, through Kansas in the 1870s and 1880s, and then blazed Gurley’s path through the Oklahoma territory in the 1890s.

“The significant thing about Greenwood is it was not just a Black thing” says James O. Goodwin. “It was quintessential America.”

Gurley knew freemen and sharecroppers would make their way to Tulsa, so he built a grocery store on an avenue he and others named Greenwood, after a town in Mississippi. Then he subdivided his land into residential and commercial lots. As Gurley expected, Greenwood soon became a beacon of wealth, education and advancement—rivaling areas of New York, Chicago and Atlanta. Doctors, lawyers and realtors flourished, luxury hotels were built, and millionaires were minted. And because all of those businesses were Black-owned, Booker T. Washington himself dubbed Greenwood “Negro Wall Street.”

“Greenwood was perceived as a place to escape oppression—economic, social, political oppression—in the Deep South,” says Hannibal B. Johnson, a Tulsa-based historian who has written numerous books about Greenwood, including Black Wall Street. “It was an economy born of necessity. It wouldn’t have existed had it not been for Jim Crow segregation and the inability of Black folks to participate to a substantial degree in the larger white-dominated economy.”

In the first two decades of the 20th century, Tulsa transformed from a dusty frontier into a thriving metropolis. Gusher after gusher was discovered and the city soon became the oil capital of the world—and Gurley’s Greenwood began to boom with it. Between 1910 and 1920, Tulsa’s population nearly quadrupled to more than 72,000 and the Black population rose from below 2,000 to almost 9,000.

By 1920, a walk through “Black Wall Street” meant traversing more than 35 bustling city blocks, with the locus being the intersection of Greenwood Avenue and Archer Street, adjacent to Tulsa’s Frisco rail tracks. The Acme Brick Company supplied building materials to the townhouses, apartments, theaters, and hotels that lined the streets. And by 1910, Black bricklayers had their own trade union called the Hod Carriers Local 199.

Paradise Found: The Dreamland Theatre was the jewel of Greenwood Avenue—until the nightmare of the 1921 Tulsa massacre.

Robert A Larson/Courtesy of Cowan’s Auctions

Entrepreneurs also began to emerge. John Williams and his wife, Loula, built a confectionary store and erected the opulent Dreamland Theater. Simon Berry built a private transportation network of Model T Fords and buses, which transported residents through Greenwood and all the way to downtown Tulsa. Berry soon began chartering planes for Tulsa’s increasingly wealthy oilmen.

Though the population was relatively small, Greenwood also had two newspapers, including the Tulsa Star founded by A.J. Smitherman. Others built pool halls, auto repair shops, beauty parlors, grocers, barber shops, and funeral homes. There was a Y.M.C.A and a roller skating rink, a hospital and a U.S. post Office substation. With all this activity, Greenwood’s economy was gushing like one of Getty’s wells. it was calculated that every dollar spent in Greenwood circulated the Black economy nearly thirty times as business thrived.

Along with this massive prosperity, the community invested in houses of worship and schools. By 1920, Greenwood had a handful of churches, most notable by the impressive Mt. Zion Baptist Church built in 1909. The district had its own elite high school, named after Booker T. Washington, which boasted a curriculum that would prepare students to eventually study at colleges like Columbia in New York, Oberlin in Ohio, and historically Black colleges such as Hampton, Tuskegee, and Spelman.

Freshman studied algebra, Latin and ancient history, as well as core subjects like English, science, art and music. Sophomores took economics and geometry, while juniors advanced to chemistry and trade-oriented subjects such as civics and business-spelling. Seniors studied physics and trigonometry, as well as vocal music, art and bookkeeping. So important was education in upwardly mobile Greenwood that teachers were among the highest paid workers. Many had their own Steinway pianos in their apartments, while the school’s principal, E.W. Woods, lived in a six-room townhouse.

Amid this bustling landscape, O.W. Gurley continued to expand his empire. At Greenwood’s peak, he owned and rented out three brick apartment buildings and five townhouses near another one of his businesses, a grocery store. He then built the Gurley Hotel, started a Masonic Lodge, and opened an employment agency for migrant workers. As Greenwood’s premier entrepreneur, Gurley built ties with residents in white Tulsa, just across the Frisco tracks, and was eventually made sheriff’s deputy, charged with policing the Black population. All told, Gurley’s portfolio was estimated to be worth more than $150,000 at the time, or nearly $2.5 million today.

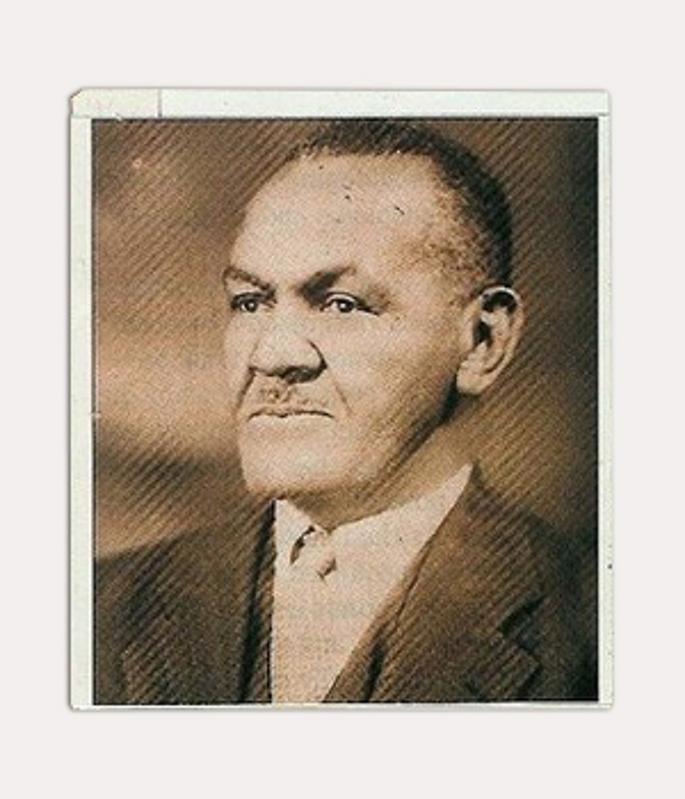

Wealthy and Wise: J.B. Stradford was one of the architects of Black Wall Street, Today, his great-grandson is among America’s premier money managers.

COURTESY OF JOHN W. ROGERS JR.

And he wasn’t the only entrepreneur to tower over Greenwood. J.B. Stradford was born in 1861, to a freed slave named J.C. Stradford, who had been emancipated in Stratford, Ontario. After settling in the South, J.C. (for Julius Caesar) named his son J.B. (for John the Baptist). The younger Stradford immediately began fulfilling his father’s dream. He graduated from Oberlin and Indiana Law School, then moved to St. Louis and Lawrenceburg, Kentucky, where he opened pool halls, shoeshine parlors, bathhouses and boarding houses. After one of his hotels went bust, Stradford moved to Tulsa in 1899 and began planning the creation of a Black community on the outskirts of town.

When Gurley arrived in 1906, the two worked in tandem building up Greenwood. Like Gurley, Stradford focused on real estate, building rentals units. The crown jewel of his portfolio was the Stradford Hotel on 301 N. Greenwood, at the time, the largest Black-owned hotel in America with 54 suites, a gambling hall, dining room, saloon and a pool hall. Stradford had built his hotel to be equal in luxury to the finest lodgings in the white Tulsa, and it stood as the big monument to Greenwood’s rising success, valued at $75,000 (or about $5 million today).

“The significant thing about Greenwood is it was not just a Black thing. It was quintessential America,” says James O. Goodwin, owner of weekly newspaper The Oklahoma Eagle, which traces its roots to Greenwood’s Tulsa Star, where his grandfather worked. Goodwin was born in Tulsa in 1939, the son of a Black Wall Street resident. “It was like any other developing neighborhood, whether that’s Irish or Greek or Jewish,” he explains. “These people embraced faith, they believed in education and hard work. They believed in capitalism and freedom.”

“People should look at Greenwood as a part of Americana, and not some aberration or a freak of nature,” he adds.

Even the first World War couldn’t derail Greenwood’s prosperity, but the disparity and tension between White and Black America was prevalent. After hundreds of thousands of Black veterans returned to Jim Crow and segregation, there was “Red Summer” in 1919, a period of white supremacist terror that dovetailed with vestigial communist fears from the 1917 Russian Revolution. Lynchings and race riots occurred across the country and the dormant Ku Klux Klan reemerged. Tulsa did not escape the racial tensions. When Oklahoma was granted statehood in 1907, the first acts of the legislature were to institute segregation. Smitherman, the publisher of the Tulsa Star, began to document lynchings across Oklahoma, in towns such as Dewey, Muskogee and Bristow.

“Greenwood shows that when we are left to our own devices and don’t have a knee to our neck, we can achieve extraordinary things,” says John W. Rogers Jr.

The violence finally exploded in Tulsa on May 30, 1921, when a Black shoeshine man named Dick Rowland was accused of sexually assaulting a white woman, Sarah Page, in the elevator of a downtown office building. The next day, the story was prominently featured in the white Tulsa Tribune, inflaming locals. A large mob formed around the jail in Tulsa where Rowland was being held and as rumors of a potential lynching circulated through Greenwood, a group of armed men marched to the jail to protect him. Tensions flared and local power brokers, including O.W. Gurley, tried but failed to make peace. According to witnesses, there was a scuffle between a white man and a Black man, a shot was fired, and a little after 10 p.m. a riot had broken out.

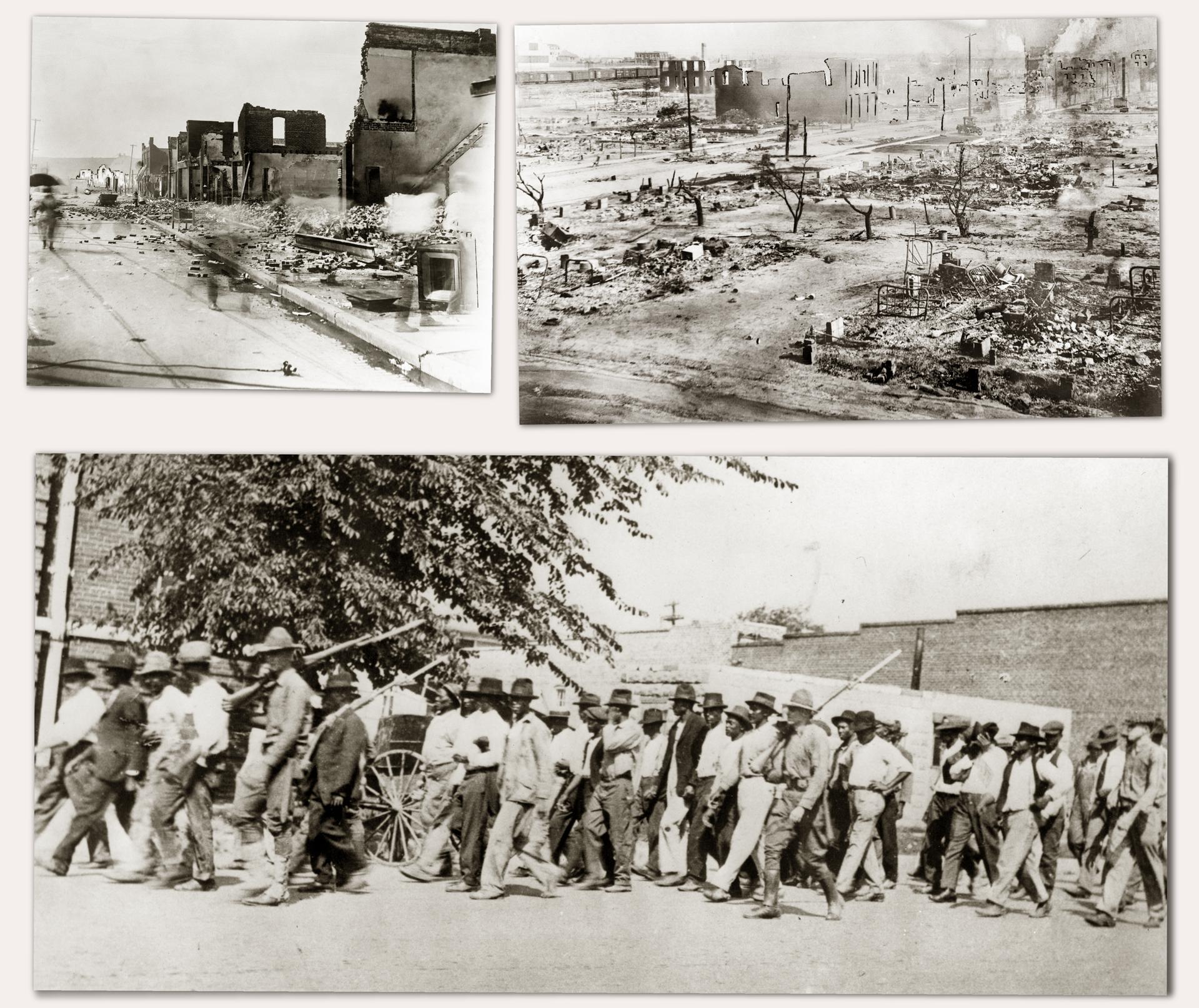

By the early morning of June 1, an armed white mob had already started burning Greenwood to the ground.

At 5 a.m. the mob began a full-bore assault on Black Wall Street. Some eyewitnesses in accounts from the 2001 Commission to study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, reported that kerosene bombs were dropped from airplanes to demolish buildings, and when the assault was over, as many as 50 whites and 200 Blacks were dead, and more than 35 square blocks had been destroyed. Those who survived the riot were rounded up by the National Guard and put in internment centers for many weeks and months. Greenwood’s total property loss neared $2 million (over $50 million now), according to some estimates, and Gurley and Stradford both lost the bulk of their fortunes as their hotels and townhouses were burned.

Most of the bodies were never recovered, presumed to have been buried in a mass grave that has still never been located. And no one was ever prosecuted or punished for the biggest racial massacre in American history.

Paradise Lost: After the destruction of Greenwood, surviving citizens were rounded up and sent to internment camps.

Getty Images

“Greenwood shows that when we are left to our own devices and don’t have a knee to our neck, we can achieve extraordinary things,” says John W. Rogers Jr., the chairman of Ariel Investments and great-grandson of J.B. Stradford, Tulsa proves that African American can build great businesses and be extraordinary successful.”

“On the other hand,” Rogers adds, “It shows you that unfortunately so many times in our history, when Black folks get a few steps ahead, we get pulled back down… It’s why the wealth gap in this country is so dramatically worse than it was 25 or 40 years ago.”

For Black Wall Street’s principal architects, O.W. Gurley and J.B. Stradford, the 1921 Tulsa riots yielded decidedly different fates. Gurley and his wife, Emma, were eventually released from the National Guard’s internment camp, while Stradford fled Greenwood, along with other residents like the Tulsa Star publisher A.J. Smitherman. Eventually, Tulsa’s police tried to blame both Stradford and Smitherman as agitators of the riot. Both had become known for challenging the uglier facets of white authority—like segregation and lynchings—and were indicted among dozens of Greenwood citizens. Gurley became a witness in the prosecutor’s grand jury case, testifying that Stradford and Smitherman had given orders to angry Blacks congregating and looking to defend Rowland from his lynching. A few whites Tulsans were indicted, but none were ever convicted.

With nothing left of Black Wall Street, Gurley left Greenwood for Los Angeles, where he died in 1935, with little indication of wealth. Stradford headed to Independence, Kansas, and then to Chicago. Though his hotel and wealth were lost in the destruction of Greenwood, his enterprising spirit passed down generations.

“My mom would often talk about how her grandfather had owned this extraordinarily successful hotel that was firebombed and destroyed during the Tulsa race riots,” says John W. Rogers Jr. “It inspired her to become a lawyer because she saw her father use legal skills to stop her grandfather’s extradition back to Tulsa. He would have been lynched if he came back. It had a profound impact on my mom.”

Rogers’ mother, Jewel, was the first Black woman to graduate the University of Chicago Law School. In 1955, President Eisenhower appointed her as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois and in the 1960s she became the first black woman to argue a case before the Supreme Court, and eventually became an influential figure in Corporate America and national politics.

Rogers graduated from Princeton University in 1980 and founded the first Black-owned mutual fund company in 1983. “J.B. Stradford was a leader among leaders in Tulsa… He wasn’t one to kowtow,” Rogers says of his great-grandfather. “Building a business and being willing to challenge authority… and fight for economic fairness, it’s something that was passed down generation to generation.” His $10 billion in assets Ariel Investments, known for its value-oriented style, is a trailblazer among a handful of thriving firms on the new Black Wall Street.

Billionaire Robert F. Smith’s $57 billion Vista Equity Partners towers over the private equity industry for its stellar returns. The same industry leadership can be seen at Baltimore’s $13 billion in assets Brown Capital Management, a Black-owned firm known for uncovering small, unheralded companies such as Tyler Technologies that grow into S&P 500 Index titans.

Though Rogers and his family stand as an emblem for economic gains that connect directly to Greenwood and Black Wall Street, the 1921 riots exemplify America’s deep and systemic economic inequities. The value plowed into Black Wall Street and lost—about $50 million in present day dollars—barely scratches the surface of the opportunities denied and dreams deferred.

Paradise Regained: A $10 million fundraising campaign was announced to restore Black Wall Street to its former glory.

AP/ Sue Pgrocki

As Rogers explains, that Greenwood money never got a chance compound. Families didn’t take their accrued wealth and reinvest it, diversify, or expand. He points to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, which shows that between 1992 and 2013, the net worth of Black people who graduated from four-year colleges dropped 55%, while white wealth rose 90%. That staggering statistic reveals decades of lost capital compounded.

“The effects of us not having multi-generational wealth and not having economic opportunity continues in our society today,” says Rogers, who supports reparations for descendants of Black Wall Street. In 2003’s Alexander v. The State of Oklahoma, hundreds of plaintiffs tracing their roots to Greenwood sued the state for $20 million in reparations, but the case was dismissed.

“All of this comes down to wealth. Wealth creates opportunity to have a better education and to live in a better neighborhood,” says Rogers, who cites Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s words, “Many white Americans of good will have never connected bigotry with economic exploitation. They have deplored prejudice but tolerated or ignored economic injustice.”

“King’s words are just as valuable today,” Rogers says. “It’s why the story of Greenwood is so important.”

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/5eec013a00caa30006a7e15f/0x0.jpg?cropX1=0&cropX2=2400&cropY1=0&cropY2=1350)