In the third episode of Netflix’s Beef, a couple that has been chatting online, speaks on the phone for the first time. Instead of conventionally discussing things they love, however, the two discuss things they hate. Bosses, brothers and everything that has caused them pain, and costed them anger. It’s the kind of conversation that reflects the gnarly social topography we now live within. In our therapized world, anger has become that unfancied, ill-reputed emotion that everyone is consistently working to disassociate from. It makes perfect sense, on paper, but Beef argues there is some power, some profundity to also letting it all out. Violence is obviously not the answer, and while show’s tragicomedy-like tone mandates some to pull in the humour, there is still an argument here for the life-affirming effects of good old meltdowns.

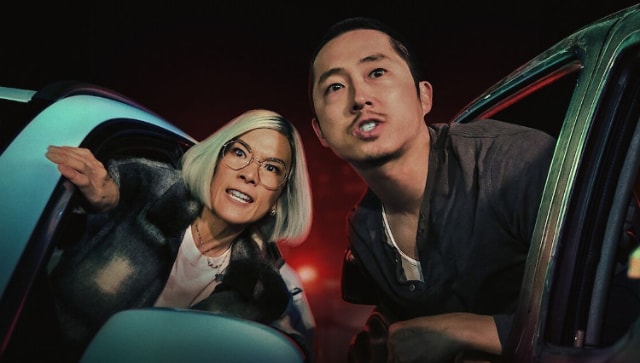

Beef tells the story of two people, at the opposite end of the class spectrum. Amy played by Ali Wong, is a horticulture entrepreneur – she grows fancy, austere, relaxing plants. All the more ironical since Amy’s own life is an entitled bubble waiting to implode. On the other end of this rope is Danny, played mercurially by Steven Yeun. He is a broke, plumbing handymen who simply can’t make things work even though that is, quite literally, the job description he must live up to. Both Amy and Danny also have people in their lives that though they assign colour and specificity to vaguely drifting trajectories, never quite redirect it towards meaning. Danny’s brother Paul, is a horny youngster who oscillates between making statements like “I think I can make at least a million dollars” to telling a woman “You’re too hot to worry about money”. Amy on the other hand is married to George (Joseph Lee), an artist, who talks, walks and operates like one, for effect.

After a road rage incident, in which Amy and Danny confront each other without ever really identifying each other, curiosity spikes the cocktail of their dull lives as they begin to channel their rage into taking the other one down. A life-affirming feud ensues, crocheted by bad decisions, hilariously immature world views and the kind of fragility that can really only become recognisable by breaking. Amy and Danny aren’t bad people per se, for they stop just short of actually twisting the knife, but they are, to an extent, looking for an outlet to merely submit all their angst to. At times, all you really need is a punching bag.

What’s perhaps most endearing about Beef is the fact that it is never quite comedy nor tragedy. It meanders and mixes with both, but never quite develops an affinity for either. This vagueness perhaps speaks more to our age than any other genre-specific story where we are actually informed about what we are supposed to feel. Life these days is so confusing, warped by a sense of impending doom and the rush to live it up at twice the speed, it has become hard to interpret reality as an emotive cue. The gravest tragedies, these days, can be written off by outrage, while the greatest comic moments, carry the umbrage of a sinister future we choose to look away from. It’s probably what makes it impossible to deposit your feelings in a specimen cup before carrying it to the psychologist to look it over. Shrinks, it turns out, can only deal with guilt and reaction. At the time, in the moment, it’s still our own deeds.

Some of Beef’s atonal provocations are exceptionally moving. They seem tragic but also come wrapped in a neat little sheath of farce. Danny breaks down in a church at one point. He then cons the same church of some money. It’s despicably dark, delicious without the conformational bias of a genre story urging you to feel a certain way. The seemingly intellectual and the seemingly underprivileged here, all make hilariously poor choices. To an extent, they are all caged, perennially concerned of the image their one moment of weakness, their one moment of unsound judgement might be interpreted as. It’s why both Amy and Danny become obsess over an incident that though it doesn’t even measure up to scale, gives them a sort of purpose, an edge to secretly but assuredly, embrace.

Beef obviously isn’t trying to endorse violence. The fact that it goes to a shrink only once, and presents it as a restrictive exercise in gaudy intellectualisation, tells you it just doesn’t fancy holding everything in. There’s a great, potentially challenging argument at the heart of this debate, the one between cure and catharsis. Amy and Danny merely symbolise a divided world where without the antagonist, nobody can really conceive their own personal heroisms. In a world that is easily and increasingly fractioned and frictional, it then makes sense to also think of the one we fight, as the one who gives us some sort of meaning. Not that hatred is good, but can love alone conquer all? Perhaps not.

Beef is streaming on Netflix.

Manik Sharma writes on art and culture, cinema, books, and everything in between.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.