By Anthony Reuben

BBC News

The government is understood to be considering raising National Insurance, to help pay for social care in England.

But there has been criticism – including from within the Conservative Party – that it would be unfair on younger people and other taxes might be more suitable.

What is National Insurance?

National Insurance is a tax paid on earnings and the profits of self-employed workers.

If you’re employed by somebody, you’ll start paying National Insurance when you’re earning just under £10,000 a year.

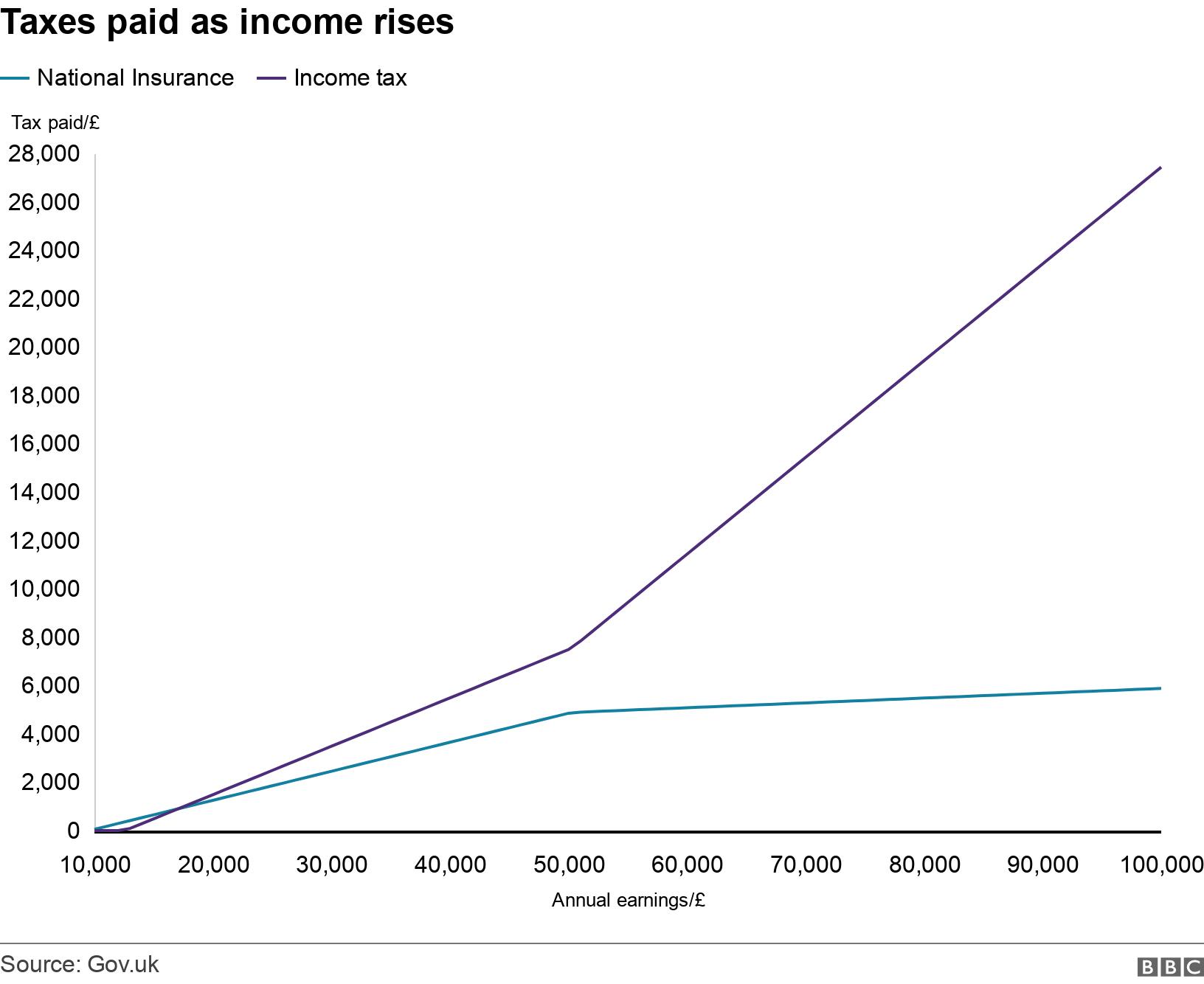

Then, you’ll pay 12% of earnings up to about £50,000 a year. Above that point you pay 2% of your earnings.

What are the criticisms of raising National Insurance?

Unlike the rate of income tax, which rises once you reach earnings of about £50,000, National Insurance falls at that point.

That means an increase would have a proportionally smaller impact on the highest earners.

And there are other features of National Insurance that might make its use unpopular.

Helen Miller from the Institute for Fiscal Studies said: “Raising National Insurance rates to fund social care would arguably be unfair, including across generations.”

She said potential problems included:

- National Insurance is not paid by pensioners, who would be the biggest beneficiaries

- It is not paid on income from investments or rental properties

- It starts being due at a lower level of earnings than income tax

Also, the government said in its 2019 manifesto, which promised a long-term solution for social care, that it would not raise National Insurance or income tax.

Former Conservative minister Jake Berry MP told the BBC that a National Insurance rise would disproportionately affect working people “on lower wages than many others in the country”, who would end up “paying tax to support people to keep hold of their houses in other parts of the country where house prices may be much higher”.

What is social care?

The social care system mainly helps older people and people with high care needs with tasks such as washing, dressing, eating and taking medication.

To get your care paid for by your local council you must have a very high level of need and also savings and assets (which may include your home) worth less than £23,250 in England.

Below that level the amount you pay reduces until you have less than £14,250, at which point the council pays for your care if you qualify.

People in residential care homes also have to pay for things like accommodation and food.

The care system is under pressure because of an ageing population and the pandemic. It has been hit by staff shortages and falling government spending.

This has also put pressure on the NHS because people cannot be discharged from hospital if they don’t have anywhere suitable to go.

How much would the National Insurance increase cost me?

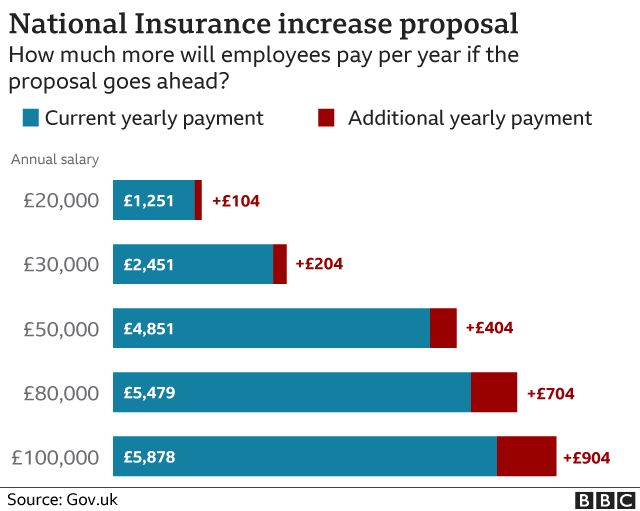

It has been reported the government is considering increasing the National Insurance rate by one percentage point.

We assume that means the starting rate of National Insurance would go up from 12% to 13%, while the rate for higher earnings goes up from 2% to 3%.

That means somebody on £20,000 a year would pay an extra £104, while someone on £50,000 would pay £404 more – as the chart below shows.

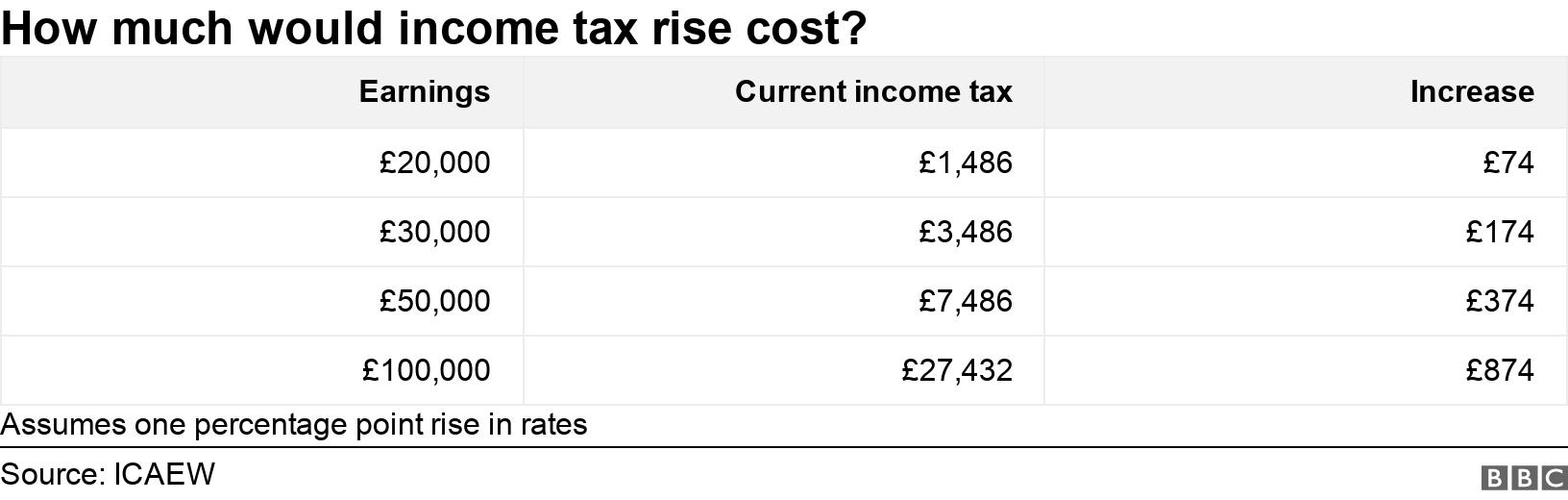

If instead of increasing National Insurance by one percentage point you increased rates of income tax by the same amount, the effect would be similar, although slightly smaller because of the higher starting rate before tax is paid.

Apart from the difference in starting point, the impact is similar because both policies would just increase the tax by one percentage point at all levels.

But it’s not just employees who pay National Insurance – it is also paid by employers, who start paying the tax of 13.8% on wages above about £9,000 a year.

If that were to be raised the extra cost to businesses could be passed on through lower wages or higher prices.

Would it raise enough money?

According to government estimates, raising the National Insurance rates for employees by one percentage point would raise about £5.4bn a year.

Increasing the rate paid by employers from 13.8% to 14.8% would raise about £6.5bn a year.

And implementing rates for others such as the profits of self-employed people would raise about another £600m.

We don’t yet know what the government’s policy for social care is, so we don’t know if that would be enough money. And it has been reported some of the extra money would go towards helping the NHS deal with its backlog of treatment caused by Covid.

Sir Andrew Dilnot, whose recommendations on capping lifetime spending on social care from 10 years ago may be adopted, told BBC News in June that an extra £10bn a year would “take us from a system that we should all be ashamed of to a system we could be proud of”.

What other options have been suggested for raising the money?

The Resolution Foundation think tank says extending a rise in National Insurance to include working pensioners would make the system fairer, although it would only raise a relatively modest £100m a year.

It also suggested increasing the level at which workers start paying National Insurance closer to the starting rate for income tax, to protect lower earners. That would be funded by increasing taxes on profits from investments.

It has also been suggested that an increase in inheritance tax could be used to help fund social care.

But it would take a big increase to the rate of inheritance tax, or a big cut to the amount that may be inherited tax-free, to raise the £10bn needed. And this could lead to people taking steps to avoid having to pay it.

At the moment, many older people who need residential care have to sell their homes, but the Conservative 2019 manifesto also said “nobody needing care should be forced to sell their home to pay for it”.

What happens in the rest of the UK?

The Westminster government only controls the situation in England.

In Wales, no-one who is eligible for care at home is expected to pay more than £100 a week.

The systems in Northern Ireland and Scotland are different for support at home and residential care.

In Northern Ireland, no-one over the age of 75 pays for home care.

Scotland provides free personal care for people who are assessed as needing support at home, whatever their age.

In Scottish care homes, people get free care if they have savings or assets of less than £18,000.

Those with savings and assets of between £18,000 and £28,750 have to fund part of their care. People with more than that have to fund their own care, apart from a £193.50 a week contribution towards personal care and £87.10 a week towards nursing care.