Tony Jolliffe / BBC

Tony Jolliffe / BBC After an almost 40-year campaign, a stunning but little-known UK landscape has been awarded world heritage status.

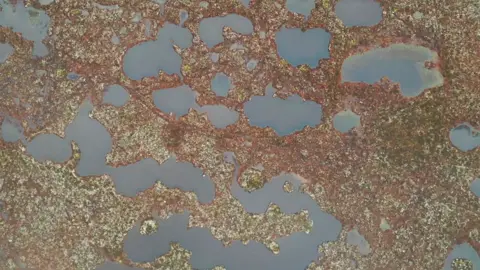

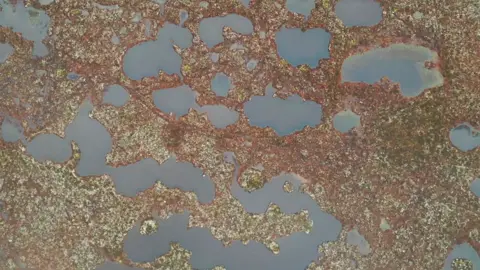

The Flow Country of Caithness and Sutherland in the far north of Scotland covers almost 2,000 sq km (469,500 acres) of one of the most intact and extensive blanket bog systems in the world.

Blanket bogs are wetland ecosystems created when peat, a soil made up of partially decayed matter, accumulates in waterlogged conditions.

Achieving world heritage status is a rare honour – particularly for a landscape. It is an internationally recognised designation awarded to places of outstanding cultural, historical, or scientific significance.

Rebecca Tanner, who has co-ordinated the project to win the site recognition, said she was delighted.

“This is just the start of the story. The real work begins now, working with the local community to realise the benefits of World Heritage status and protect the Flow Country for generations to come.”

The award is made by Unesco, a UN organisation that promotes cooperation on education and science.

It means this vast tract of peat bog joins just 121 landscapes worldwide which have been awarded the designation.

Only two of these are on the UK mainland: the “Jurassic Coast” in Dorset and the Giant’s Causeway on the coast of Northern Ireland.

As well as peatland and bogs, the Flow Country includes pools, lochs, hills and mountains covering a total of 4,000 sq km of land that stretches across virtually the whole reach of the north Highlands.

The rare blanket bog ecosystem supports a range of notable species including a host of sphagnum mosses and other wetland plants. There are all sorts of insects here too, and a host of rare birds including greenshank, golden plover, dunlin and hen harrier.

The region is home to otters and water voles as well as large numbers of sundews – carnivorous plants that ensnare insects on the sticky surfaces of their leaves which they then ingest, supplementing the meagre nutrition provided by the peaty soil.

The vast bog also represents an important bulwark against climate change.

The peat deposits have been building up since the vast ice sheets that covered most of the UK during the ice age began to melt away around 10,000 years ago.

It means the peat deposits retain huge quantities of the carbon the plants absorbed as they grew.

In places the peat deposits are reckoned to be 10m thick – deep enough to submerge two double decker buses stacked on top of one another.

It has been estimated the entire system could contain as much as 400m tonnes of carbon, which is reckoned to be twice that contained in all of Britain’s woodlands.

As the mosses and other bogland vegetation die off they only partially rot away because of the acidic conditions in the water.

The area also has historical significance with evidence of human activity dating back thousands of years.