In an exclusive excerpt from No Rules Rules, the billionaire founder of the streaming giant rewinds history to look at how he almost missed the big picture.

At most companies, the manager’s role is to approve or block the decisions of employees. This is a surefire way to limit innovation and slow down growth. At Netflix, we emphasize that it’s fine to disagree with your manager and to implement an idea she dislikes. We don’t want people putting aside a great idea because the boss doesn’t see how great it is. That’s why we say: DON’T SEEK TO PLEASE YOUR BOSS. SEEK TO DO WHAT IS BEST FOR THE COMPANY. They are not always the same thing. It’s one of the many ways that we give our employees freedom and responsibility that is far beyond what many other organizations typically do.

Good decisions, however controversial, require a solid grasp of the context, feedback from people with different perspectives, and awareness of all the options. If someone uses the freedom Netflix gives them to make important decisions without soliciting others’ viewpoints, we consider that a demonstration of poor judgment. One way to collect those viewpoints is to “farm for dissent,” or “socialize” the idea.

This premise of farming for dissent came out of the Qwikster debacle, the biggest mistake in Netflix history. In early 2011, we offered one service for ten dollars that was a combination of mailing DVDs and streaming. But it was clear that streaming video would become of increasing importance while people would watch fewer and fewer DVDs.

In Your Cart: With Qwikster, Hastings tried (and failed) to separate Netflix’s DVD rental business from its streaming service.

(Photo By Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

We wanted to be able to focus on streaming, without DVDs distracting us, so I had the idea to separate the two operations: Netflix would stream, while we created a new company, Qwikster, to handle the DVD market. With two separate companies, we would charge eight dollars for each service separately. For customers who wanted both DVDs and streaming, it meant a price hike to sixteen dollars. The new arrangement would allow Netflix to focus on building the company of the future without being weighed down by the logistics of DVD mailing, which was our past.

Although the thinking behind the move—that streaming would be our future—was correct, the announcement provoked a customer revolt. Not only was our new model way more expensive, but it also meant customers had to manage two websites and two subscriptions instead of one. Over the next few quarters, we lost millions of subscribers and our stock dropped more than 75 percent in value. Everything we’d built was crashing down because of my bad decision. It was the lowest point in my career—definitely not an experience I want to repeat. When I apologized on a YouTube video, I looked so stressed that Saturday Night Live made fun of me.

But that humiliation was a valuable wake-up call, because afterward dozens of Netflix managers and VPs started coming forward to say they hadn’t believed in the idea. One said, “I knew it was going to be a disaster, but I thought, ‘Reed is always right,’ so I kept quiet.” A guy from finance agreed, “We thought it was crazy, because we knew a large percentage of our customers paid the ten dollars but didn’t even use the DVD service. Why would Reed make a choice that would lose Netflix money? But everyone else seemed to be going along with the idea, so we did too.” Another manager said, “I always hated the name Qwikster, but no one else complained, so I didn’t either.” Finally, one VP said to me, “You’re so intense when you believe in something, Reed, that I felt you wouldn’t hear me. I should have laid down on the tracks screaming that I thought it would fail. But I didn’t.”

The culture at Netflix had been sending the message to our people that, despite all our talk about candor, differences of opinion were not always welcome. That’s when we added a new element to our culture. We now say that it is unacceptable and unproductive when you disagree with an idea and do not express that disagreement. By withholding your opinion, you are implicitly choosing to not help the company. I can’t make the best decisions unless I have input from a lot of people. That’s why I and everyone else at Netflix now actively seek out different perspectives before making any major decision.

We call it farming for dissent. Normally, we try to avoid establishing a lot of processes at Netflix, but this specific principle is so important that we have developed multiple systems to make sure dissent gets heard. For example, if you are a Netflix employee with a proposal, you create a shared memo explaining the idea and inviting dozens of your colleagues for input. They will then leave comments electronically in the margin of your document, which everyone can view. Simply glancing through the comments can give you a feeling for a variety of dissenting and supporting viewpoints.

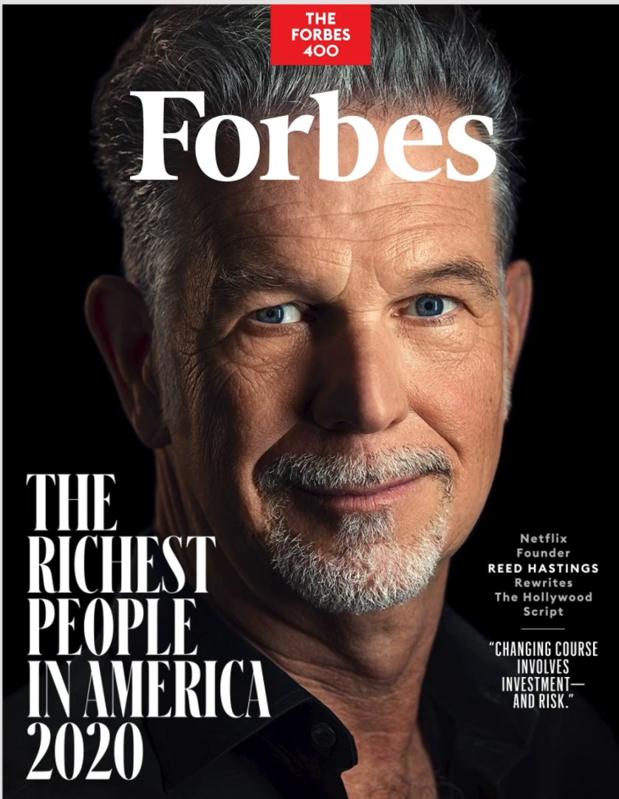

The author on the October 2020 cover.

Forbes

In some cases, an employee proposing an idea will distribute a shared spreadsheet asking people to rate the idea on a scale from –10 to +10, with their explanation and comments. This a great way to get clarity on how intense the dissent is and to begin the debate. Before one big leadership meeting, I passed around a memo outlining a proposed one-dollar increase in the price of a Netflix subscription along with a new tiered-pricing model. Many dozens of managers weighed in with their ratings and comments. The spreadsheet system is a super-simple way to gather assent and dissent, and when your team consists entirely of top performers, it provides extremely valuable input. It’s not a vote or a democracy. You’re not supposed to add up the numbers and find the average. But it provides all sorts of insight. I use it to collect candid feedback before making any important decision. The more you actively farm for dissent, and the more you encourage a culture of expressing disagreement openly, the better the decisions that will be made in your company. This is true for any company of any size in any industry.

‘No Rules Rules’ co-authors Erin Meyer and Reed Hastings.

Penguin Random House

For smaller initiatives, you don’t need to farm for dissent, but you’d still be wise to let everyone know what you’re doing and to take the temperature of your initiative. Socializing is a type of farming for dissent with less emphasis on the dissent and more on the farming. In 2016, I had a personal experience where socializing an idea led me to change my own opinion. Up until then I believed strongly that kids’ TV shows and movies would not bring new customers to Netflix or even retain the customers we had. Who signs up to Netflix for a children’s show? I was convinced adults choose Netflix because they love our content. Their kids will just watch whatever we have available. So when we began producing original programs, we focused on adult content only. For kids, we continued to license shows from Disney and Nickelodeon. And when we did release our own Netflix kids shows, we didn’t put much money into them, not in the way Disney did. The kid’s content team disagreed with this approach: “These are the next generation of Netflix customers,” they argued. “We want them to love Netflix as much as their parents do.” They wanted us to start producing original kids’ content as well.

Penguin Random House

I didn’t think that was a great idea but I socialized it anyway. At our next quarterly leadership meeting we placed our top four hundred employees at sixty round tables in groups of six or seven. They received a small card with this question to debate: Should we spend more money, less money, or no money on kids’ content? There was a tsunami of support for investing in kids’ content. One director who is also a mom got up onstage and passionately declared, “Before working here I subscribed to Netflix exclusively so my daughter could watch Dora the Explorer. I care a lot more about what my kids watch than what I watch myself.” A father came up and announced, “Before coming to Netflix I only subscribed because I could trust the content for my children.” He explained why: “On Netflix there’s no advertisements like on cable and no dangerous rabbit holes for my son to fall down like when he surfs on YouTube. But if he hadn’t been crazy about what Netflix was offering, he’d have stopped watching and we’d have canceled the subscription.” One after another our employees were stepping onto that stage and telling me I was wrong. They believed kids shows were critical to our customer base.

Within six months we’d hired a new VP of kids and family programming from DreamWorks and started making our own animated features. After two years we’d tripled our kids’ slate, and in 2018 we were nominated for three Emmys for our original kids shows Alexa and Katie, Fuller House, and A Series of Unfortunate Events. To date, we’ve won over a dozen Daytime Emmys for children’s programs like The Mr. Peabody and Sherman Show and Trollhunters: Tales of Arcadia, from Guillermo Del Toro. If I hadn’t taken the time to socialize the idea, none of this could have happened.

From No Rules Rules by Reed Hastings and Erin Meyer. Published by arrangement with Penguin Press, a member of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright (c) Netflix, Inc., 2020.

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/5f5a83655b11eb9993f88da2/0x0.jpg?cropX1=0&cropX2=4641&cropY1=115&cropY2=2724)