This NFL season’s opening game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the Houston Texans featured two of the most exciting young talents in the game: 2018 league MVP and 2020 Super Bowl MVP Mahomes of the Chiefs and the Texans’ Deshaun Watson.

Are we seeing a change in attitudes and treatment, or is the struggle still as prevalent as ever?

Historic experience

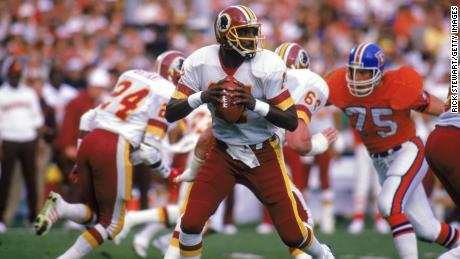

Few know the battle African American quarterbacks have faced like Warren Moon. The 63-year-old Moon, is the only Black quarterback in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, but didn’t have an easy route into the league.

Having gone undrafted in 1978, Moon went to Canada, winning five consecutive Grey Cups — the Canadian Football League title — before he was given a chance in the NFL with the Houston Oilers in 1984, aged 28. He says what he experienced wasn’t racism, but rather racial stereotyping stacked against him.

“If it was racism then they [Black players] wouldn’t be allowed to play the game at all,” he told CNN. “But the stereotype was that we can only play certain positions.

“And the quarterback position was the position that a lot of people didn’t think we could play for different reasons, whether it was the leadership, whether it was being able to think, be able to make critical decisions at critical times. You know, be the face of a franchise, all those different things that go along with being a franchise quarterback.”

While Moon believes things have improved for Black quarterbacks since he entered the league, has enough changed?

In a response to CNN, the league in a statement said: “There are a record-setting 10 starting Black quarterbacks this season. The two highest-paid players in the NFL are Black quarterbacks. The last two seasons’ MVPs have been Black quarterbacks.

“The NFL is undertaking short-, intermediate-, and long-term diversity identification initiatives for both non-football and football personnel to ensure more opportunities for African Americans in leadership management positions across the league.”

League entry

The battle for Black quarterbacks begins with entry into the NFL. According to a leading academic, Black quarterbacks have historically found it more difficult being drafted into the league than their White counterparts.

Dr. Judson L. Jeffries, a professor of African American and African studies at the Ohio State University, says Black quarterbacks have been historically perceived as less intelligent, seen instead as simply athletes.

“The knock on Black quarterbacks was they didn’t have the intellect or academics to play the position,” he tells CNN. “They could run, but when it comes to learning a playbook, reading defenses, learning sophisticated schemes, they weren’t able to do that.”

Though Jeffries thinks a lot has changed in the intervening 12 years since his study, he continues to have reservations about whether perceptions of Black and White quarterbacks are equal.

“Now it appears in 2020, much to my surprise but much to my delight, that [prejudice] has dissipated significantly in terms of judging Black quarterbacks that way,” he says.

“However, here’s the rub: Even though things have significantly progressed, a lot of scouts and coaches when they see an African American quarterback will immediately frame them as someone who is a great athlete, as opposed to someone who is a great quarterback.”

Jeffries cites the treatment Jackson received when he entered the league.

A Heisman Trophy winner as a sophomore at the University of Louisville, Baltimore Ravens’ Jackson was seen by doubters as just a runner, rather than someone who could throw, make critical decisions and lead too.

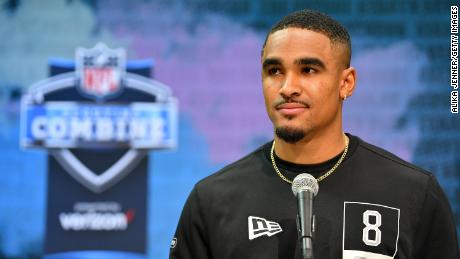

At the 2018 NFL Scouting Combine, he refused to take part in run drills, such as the 40-yard dash, to draw people’s attention to his passing ability.

Jeffries says Jackson’s decision not to take part in running drills, especially the 40-yard dash, was a significant moment in NFL history.

“That was huge,” he says. “In terms of standing his ground, verbally, and being vocal that [he is] a quarterback.

“Coupled with that, [Jackson’s decision to say] ‘I am not going to participate in the kind of drills that will undermine my ability to be viewed as a quarterback and drafted as a quarterback.'”

In other words, Jeffries says, “Don’t draft me and then talk about me playing wide receiver or running back.”

Unfortunately for Jackson, teams that needed quarterbacks didn’t want to take the risk.

The reigning NFL MVP, and only the second unanimous MVP in NFL history, Jackson has since proved the doubters wrong.

Jeffries says he thinks others in a similar position to Jackson will be inspired and are “more likely to stand their ground verbally,” but “the jury is still out to what degree they will actually take that stand that Lamar Jackson took.”

Jalen Hurts, a 2020 second round selection for the Philadelphia Eagles, went through a similar process after experiencing significant success in college.

With Alabama, he reached the 2017 College Football Playoff title game as a true freshman and was the starting quarterback of the 2018 championship team. After losing playing time the following season to Tua Tagovailoa and winning the SEC title game as an injury replacement, Hurts transferred to Oklahoma and excelled. He finished second in the Heisman Trophy vote his senior year.

“In my first year, what annoyed me more than anything is that people thought it was just my arm,” Mahomes said. “Everybody just talked about my arm instead of talking about how I was making the right decisions, going to the right place.”

He compared his experience to that of Ravens quarterback Jackson. “He threw for over 30 touchdowns, but everybody just wanted to talk about the runs.”

Scrutiny and prejudice

Murray proved the doubters wrong by winning the 2019 NFL Offensive Rookie of the Year award.

The draft positions of some Black quarterbacks have raised some eyebrows.

“So, when you start talking about ‘a guy can’t comprehend’ — that stuff is racial.”

The Giants were contacted by CNN but declined to comment.

Positions of power

“Today it’s systemic,” he said. “They are afforded opportunities, but they aren’t allowed to be average because they don’t have enough decision-makers who look like them.”

Avery said without Black coaches, coordinators and general managers, opportunities for Black quarterbacks are limited.

During the same time period, six of the 31 departing head coaches, coordinators or general managers were men of color. This means the NFL only made a net gain of one person of color in one of these positions of power from 2019 to 2020.

In its response for comment, the NFL told CNN “enhancements to [the] Rooney Rule will increase opportunities for growth, development, and advancement for minorities across all facets of the League and clubs, both for non-football employees and football personnel.”

The statement added: “The league is also implementing universal data collection to gather diversity information from all 32 NFL clubs. This information includes demographic details by position such as race/ethnicity, gender, generation, and more.”

Positive change?

Moon, however, is positive about the direction the league is going, saying Black quarterbacks are now getting the opportunities he wasn’t when trying to break into the NFL.

“African American quarterbacks now are getting more opportunities than they ever have before,” he says. “And I think that’s why you see so many of them flourishing in the league right now.”

The current crop of supremely talented African American quarterbacks, says Moon, are successfully changing people’s perceptions of Black quarterbacks.

“Somebody said success is when [you do] something other people want to copy. You see African American quarterbacks are doing very, very well,” he says, reeling off the achievements of Wilson, Murray, Mahomes and Jackson.

“When other teams see this, they say, ‘I want to have a successful quarterback, maybe this is what I need.’

“When African Americans have success, it’s going to breed more opportunities for other African Americans. That’s what you see going on right now.”

Moon knows that the work he and other quarterbacks, like Doug Williams — the first Black quarterback to win the Super Bowl and to be named Super Bowl MVP — paved the way.

“We also know that if we did well, if we played well at a high level, that is going to help the next generation of guys get more opportunities,” he says.

“And we sit down, we see the game flourishing at that position right now for African Americans. It makes us all proud.”

Eric Bieniemy, the Kansas City Chiefs’ offensive coordinator, himself an African American, believes it’s time to end labels, and says current Black quarterbacks think so too.

“All of these guys just want to be labeled as a football player,” he said in an August press conference. “They want to be labeled as a quarterback. They don’t care about their skin color.

“They just want to make sure that they’re representing and doing it the right way and providing a road map for the next upcoming young black African American.”