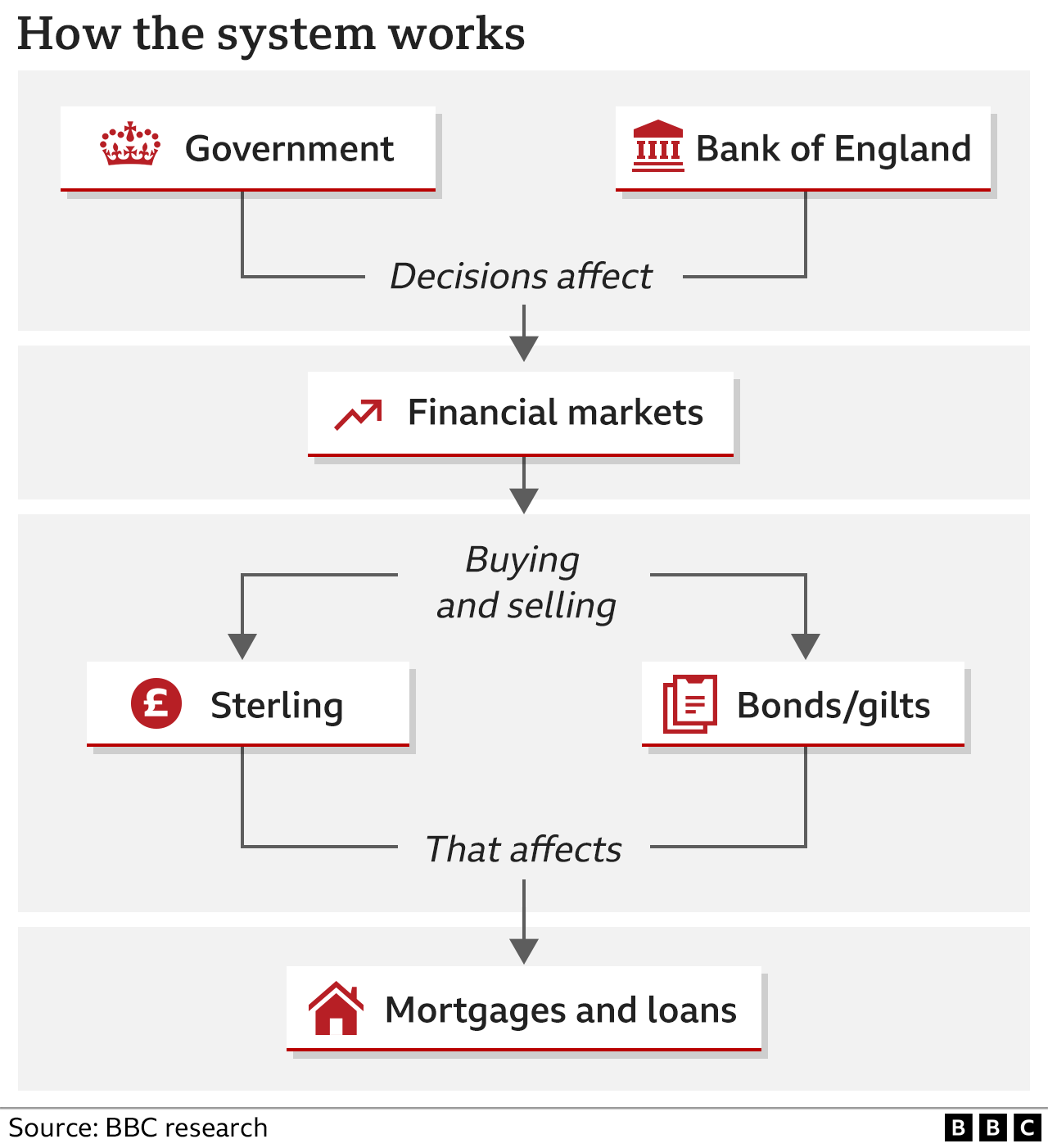

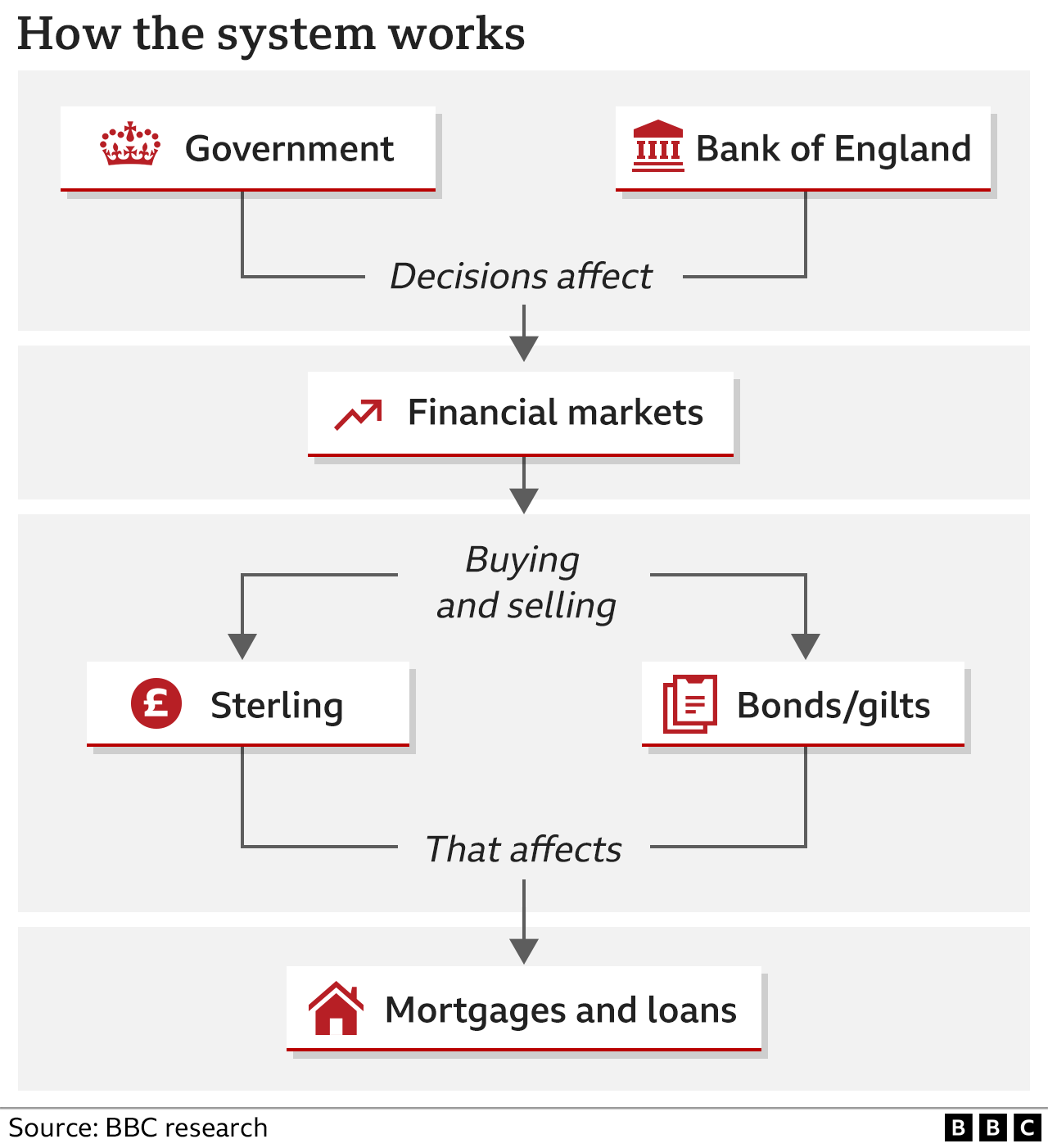

The government has scrapped most of the key elements of its mini-budget after just over two weeks – but why did it have to respond to the turmoil in the financial markets and why does this matter to mortgage payers and everyone else?

1. What did the government do?

The government’s job is to decide how much to spend on the things we need like the NHS, defence and education but also how to pay for them – which it does using taxes and by borrowing money.

The government had announced help for people with their energy bills but the mini-budget on 23 September didn’t explain how it would be paid for. In fact it announced lots of tax cuts – suggesting that borrowing would have to rise even more than expected to make up the difference.

2. How does the government borrow money?

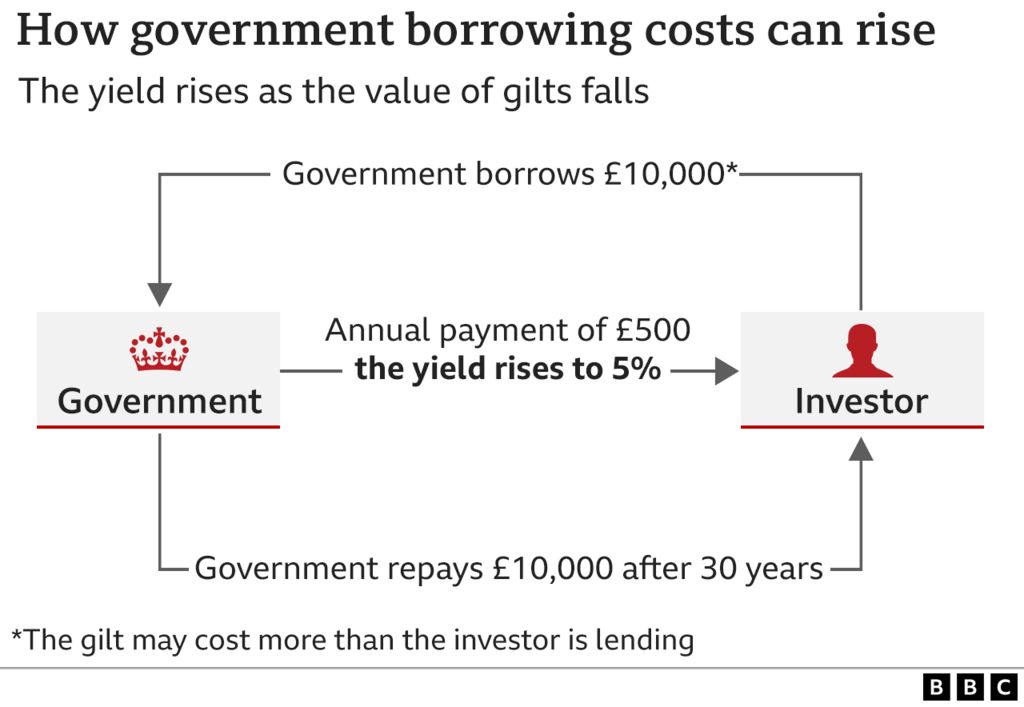

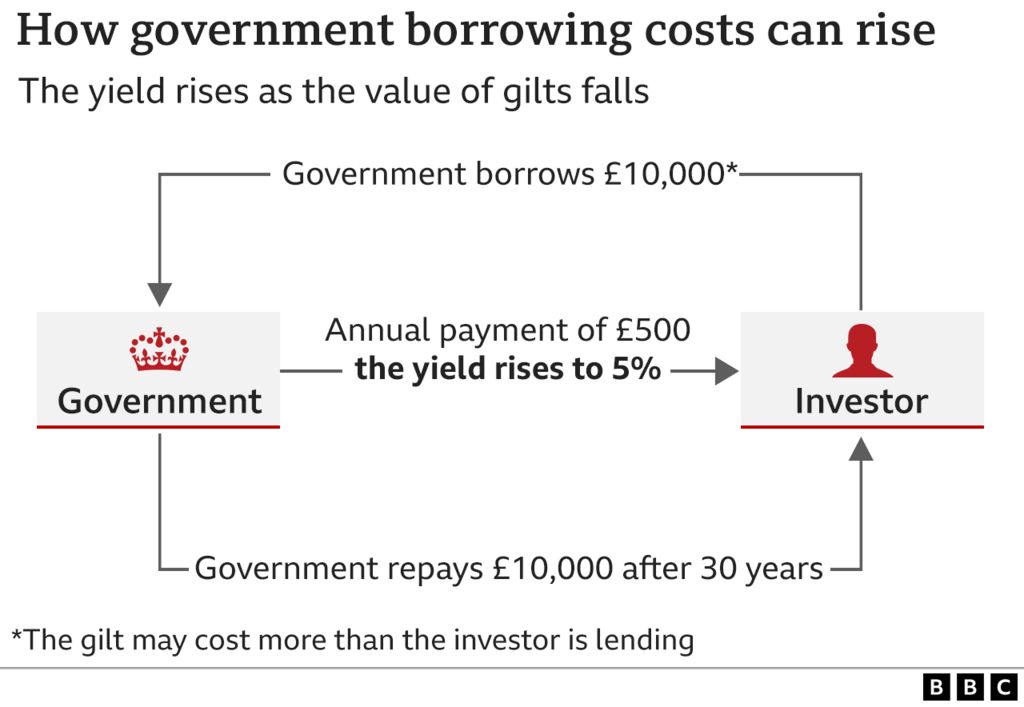

The government borrows money from investors with a type of contract known as a bond or gilt – basically it promises to repay the money after a set period of time and pays a fixed yearly amount to the investor as a fee.

The yield is a way to describe the amount the investor gets.

3. Where do the markets come in?

The term markets refers to investors, and the biggest players – those with the most money such as investment banks, pension funds and insurance firms – were worried about the amount the government would have to borrow to pay for its mini-budget.

They were concerned the government wouldn’t be able to pay back the money it owed them, and also that the loans would be worth less when they were repaid as a result of inflation (how much things go up in price over time).

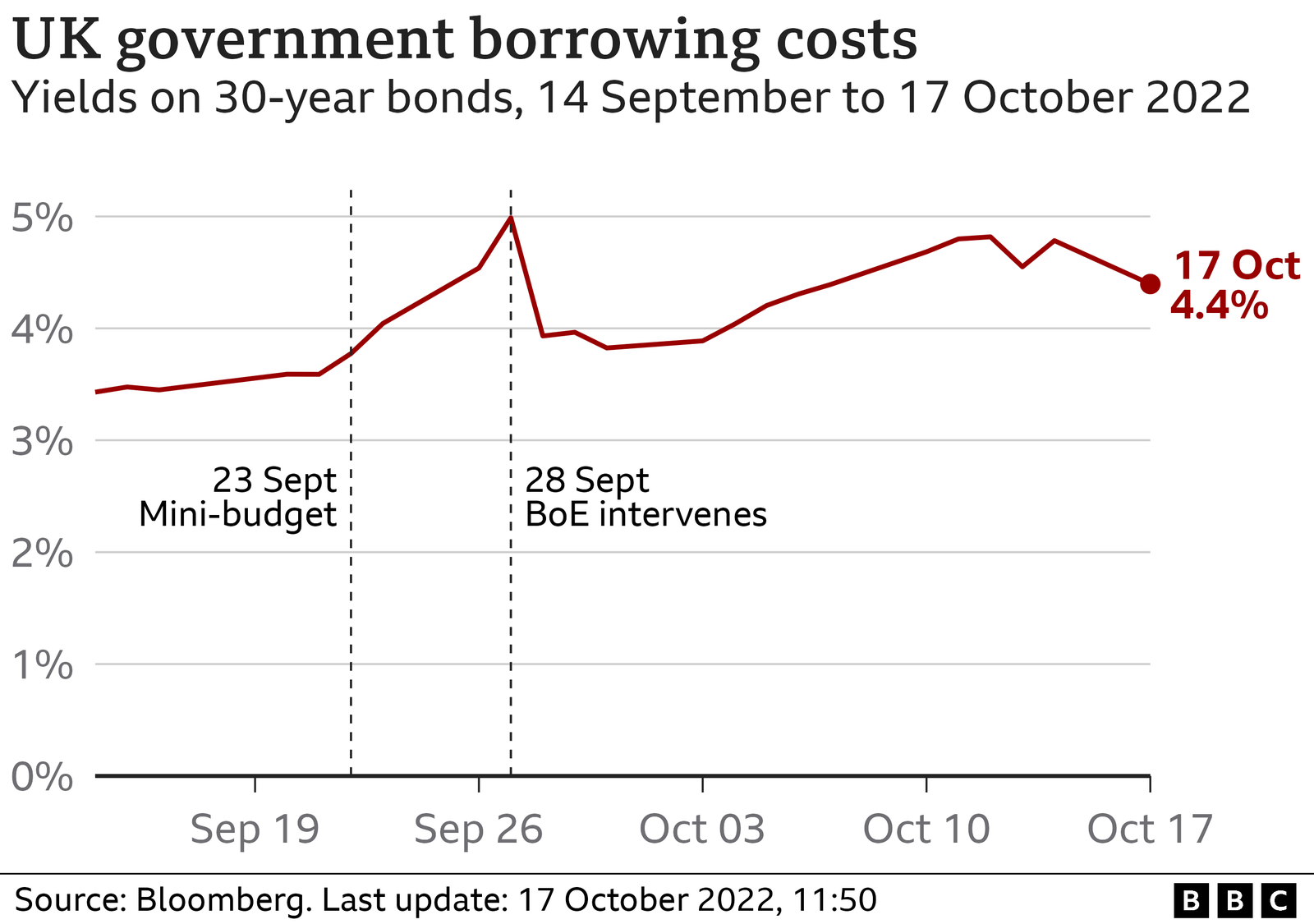

As a result they weren’t prepared to buy gilts for as much as investors had previously paid. That also meant the government had to pay a higher yield to persuade investors to buy new gilts – so it cost more for the government to borrow money.

4. Why were pension funds an issue?

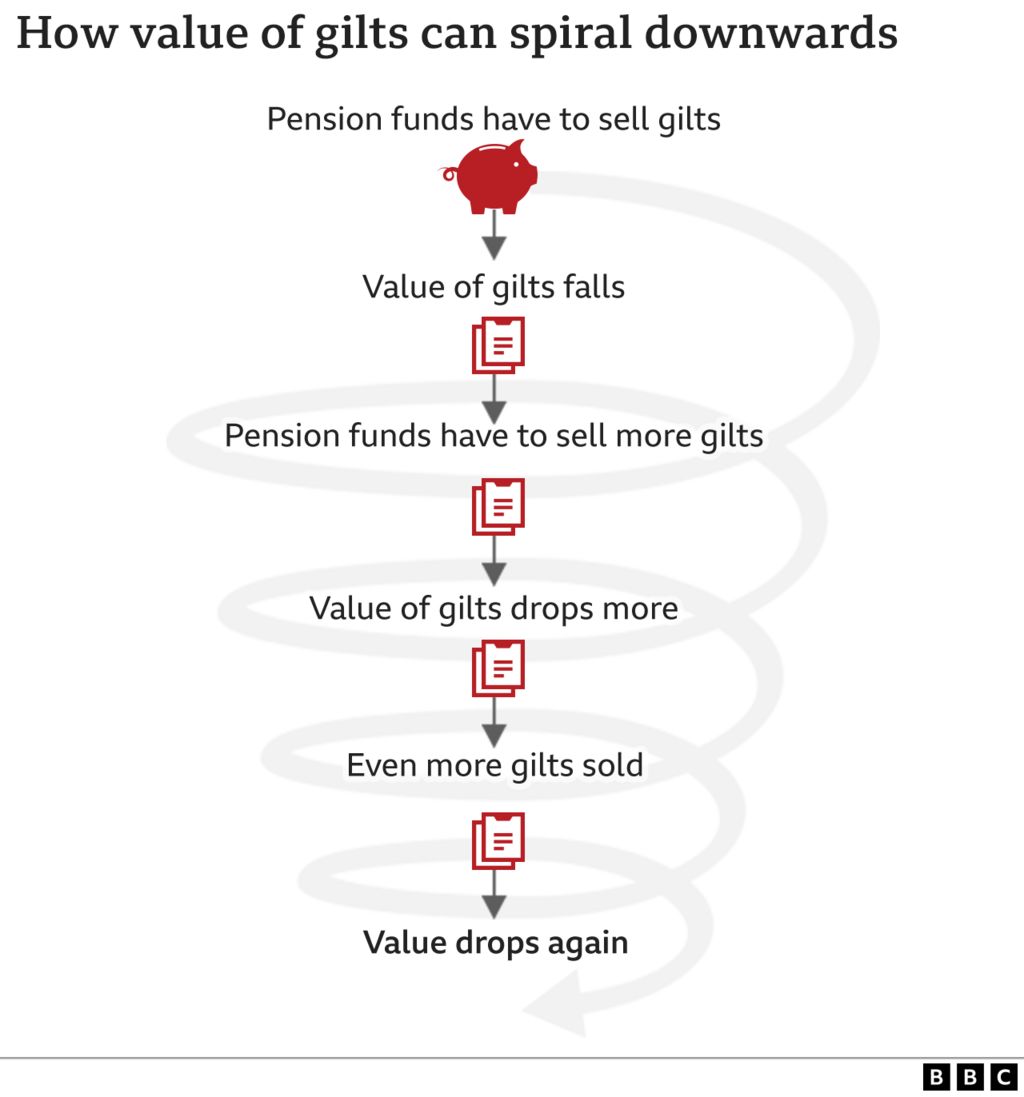

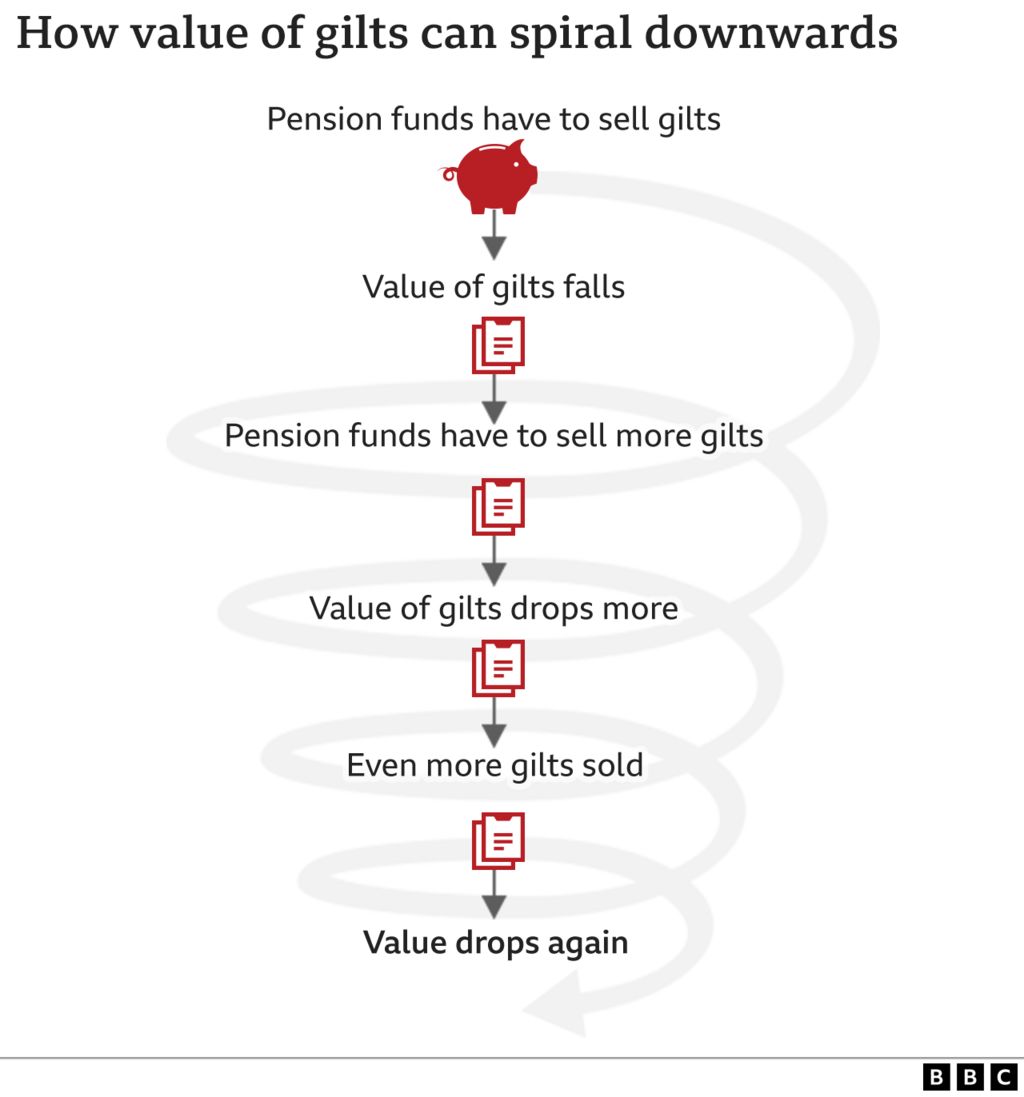

As well as buying gilts, some pension funds use them as guarantees to borrow money from banks so that they can pay people’s pensions – they then sell the gilts to repay the money to the banks.

But when the value of gilts fell after the mini-budget, pension funds had to sell more to raise the same amount of money to repay their loans. With more gilts being sold, their value fell further and this risked creating a downward spiral that could have left some pension funds unable to pay their debts.

5. What did the Bank of England do?

The Bank of England is independent from the government but has instructions to keep the country financially stable – something that would have been at risk if lots of big pension funds had collapsed.

It stepped in on 28 September and promised to buy gilts to stop their price dropping any further – effectively acting as a backstop and putting a floor on the price of a gilt and a ceiling on the yield. But that support finished on 14 October.

6. What happened to the pound?

Concerns about the mini-budget on 23 September also made the pound less attractive to investors – so the value of sterling (the pound’s official name) fell when compared with the dollar.

That meant it would cost more to import things we needed from abroad and would push up inflation.

The Bank of England is expected to keep inflation at about 2% and it usually does this by making it more expensive for people to borrow money – putting up interest rates to encourage people to save instead of spend.

7. Why did all this affect mortgages?

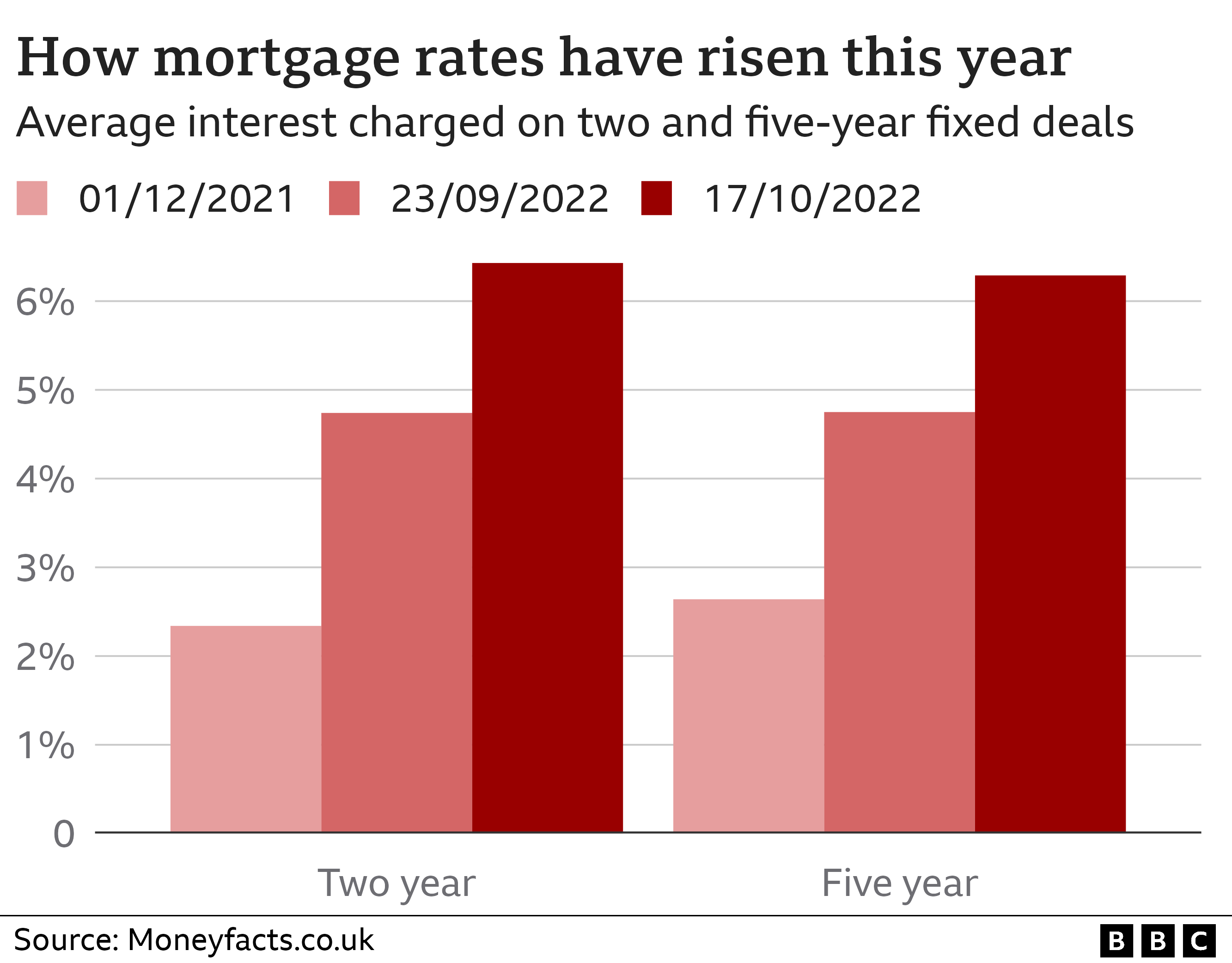

The Bank of England hasn’t raised its interest rates since the mini-budget but High Street banks believe it will have to do this – one reason mortgage rates are rising.

In addition, High Street banks raise money from the markets, which they then lend to customers in mortgages and other loans, but they have to offer investors higher interest rates than the government because they are seen as riskier investments.

This feeds through to the interest rates banks charge us – so when it costs the government more to borrow money, it makes our mortgages and other bank loans more expensive.

8. So where are we now?

With the Bank of England’s promise to buy gilts ending on 14 October, the government needed to act to reassure the markets that it would not be borrowing too much money to avoid the whole cycle starting again.

Chancellor Jeremy Hunt has cancelled almost all of the tax cuts announced in the mini-budget and says the help given to people for energy bills will be more limited. Now all eyes will be on what happens to gilts and sterling – and as a result to our mortgages and bank loans.

Graphics by Zoe Bartholomew and Gerry Fletcher