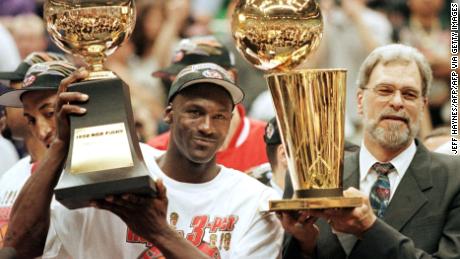

Both events were profiled in the latest episode of the blockbuster 10-part documentary series, ‘The Last Dance,’ airing on ESPN in the US with Netflix having the international rights. The show chronicles Jordan’s epic final season with the Chicago Bulls.

While his sublime talent has never been in question, and his six NBA titles in the 1990s remain an almost mythical accomplishment, some questions have lingered about the man behind that myth.

Air Jordan

It seems unthinkable now that the superstar who sold millions of basketball shoes with Nike wasn’t even interested in meeting with the company in the first place. In the early 1980s, Nike was a fledgling start-up in Portland, Oregon, a brand more synonymous with manufacturing track shoes.

HIs agent, David Falk, asked Jordan’s parents to persuade him to get on the plane. “My mother said ‘you’re going to go and listen. You may not like it, but you’re going to go and listen,'” Jordan recalled in episode five of the hit television series.

The rest is history. The “Air Jordan” was born and both Jordan and Nike immediately hit the jackpot.

As Falk put it: “By the end of year four, Nike hoped to make $3 million in sales. But by the end of year one, they’d made $126 million.” The shoe was iconic and so was he, a team player marketed more like a tennis player or a boxer. A talented, handsome athlete who quickly emerged as a global pop-culture sensation.

“Michael came right at a time when satellite TV and cable TV were proliferating,” ‘The Last Dance director’ Jason Hehir told CNN Sport. “He had the looks, he had the charisma. He was well spoken. He was intelligent and he was probably the most captivating performer in the history of the NBA. It was a perfect storm.”

Pretty much everything that Jordan has touched turned to gold. His narrative is inspirational, his dedication almost impossible to rival and his enthusiasm infectious. Watching him grinning from ear to ear on the sidelines at the 1998 All Star game, you can almost feel the joy wafting into your veins.

Jordan helped establish Chicago as a major player on the world sports map. Before his arrival in the summer of ’84, the Bulls were known as the “traveling cocaine circus” and he didn’t just clean up the team, he arguably helped clean up the city.

“The reputation of Chicago was kind of gangland and corrupt politicians,” mused Hehir. “It was the home of Al Capone, mob gangster stuff. That city was fiercely divided on color lines, one of the hotbeds of prejudice in the country and Michael united people.”

Politics

Sports anchor Dan Roan had a ringside seat from his vantage point at the Chicago TV station WGN.

“Everybody was a Bulls fan, no matter your political preference,” Roan told CNN Sport. “It didn’t matter where you lived, it was kind of a galvanizing issue for the city.”

If Jordan had transcended Chicago, not everybody was content with him being only a basketball player.

In 1990, a senate race in North Carolina presented a quandary for the NBA star. Charlotte’s first African American mayor Harvey Gantt, a Democrat, was trying to unseat Republican Jesse Helms to become the state’s first black senator.

Helms had campaigned doggedly to try and prevent the senate from approving a federal holiday to honor the civil rights icon Dr. Martin Luther King.

“My mother asked me to do a PSA about Harvey Gantt,” Jordan recalled in ‘The Last Dance.’ “I said, ‘Look mom, I’m not speaking out of pocket about something I don’t know, but I will send a contribution to support him.'”

Gantt lost the election, but it was Jordan’s off-the-cuff remark on the team bus — “Republicans buy sneakers too” — that defined his position in the eyes of his critics. Jordan admits that he said it, “as a joke,” but he’s been haunted by those four words for decades.

While the Chicago native, former President Barack Obama, would have preferred Jordan to enter the political fray, he has some sympathy for his stance, saying in the film: “America is very quick to embrace a Michael Jordan, an Oprah Winfrey or a Barack Obama, so long as it’s understood that you don’t get too controversial around broader issues of social justice.”

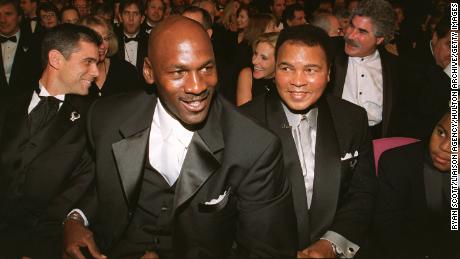

Still, if you’ve ever wondered why Jordan isn’t mentioned in the same breath as Muhammad Ali, this is arguably the reason why.

“I do commend Muhammad Ali for standing up for what he believed in, but I never thought of myself as an activist,” Jordan affirms. “I thought of myself as a basketball player. Was I selfish? Probably.”

And Jordan makes no apology. “I set examples and if it inspires you, great. And if it doesn’t, then maybe I’m not the person you should be following.”

Roan is reluctant to join those who criticize Jordan’s unwillingness to get involved in matters beyond basketball, pointing out the superstar rarely made any kind of public appearance. But he was also quick to add that “had he been able to do some more social stuff, I think he would have been so impactful.”

Then there’s the question of whether or not Michael Jordan is the kind of guy you’d want to hang out with. There’s a well-known phrase in sports — “nice guys finish last” — so what does that say about Jordan?

“Everything you think it might say about him,” chuckles Roan, who arrived in Chicago just a few months before Jordan in 1984.

“He was great to me, but when somebody was trying to play basketball against him or when he had an issue with somebody in the front office like (general manager) Jerry Krause, Michael could be a pretty mean customer.”

Intense rivalry

Roan vividly recalls the time he witnessed Jordan egging on his teammate Scottie Pippen, who famously had an acrimonious relationship with Krause, to take the wheel off the bus and run him over, exclaiming, “Now’s your big chance!”

His former Bulls teammate, Horace Grant, described Jordan as a devil in the documentary, saying, “You make a mistake, he’s going to scream at you, he’s going to belittle you.”

And time certainly hasn’t healed the intensity of Jordan’s rivalry with opponents like the Detroit Pistons, “I hated them then and that hatred continues even to this day.”

But during the production of ‘The Last Dance,’ director Hehir found Jordan to be nothing but kind and considerate.

“I think a lot of Michael as a guy, he was nothing but respectful to me and to my camera crew and to the entire production staff. Our makeup artist was pregnant and he admonished somebody wanting to light up a cigar. He says ‘ma’am’ and ‘sir.’ I mean, he’s a country kid at heart.”

For Hehir, Jordan’s personality is one of the most fascinating things about him.

“I was interested in getting his perspective on how he feels as a ‘nice guy’ to not be perceived as one. I was interested if he had any ambivalence about that.”

‘The Last Dance’ is a captivating waltz down memory lane; the main drama played out 22 years ago, in a more innocent time, before we were all obsessed with our mobile phones and social media.

It’s hard to imagine that the goldfish bowl that Jordan, Pippen and Dennis Rodman were swimming around in could have been even more intense than it actually was at the time.

“I think the coverage of the Bulls today would be much different than it was then,” Roan speculated.

“All the haters out there trying to pile on. It may have been different enough to affect the way they went about winning their games. My feeling is that were he playing today, he’d really close himself off, worry about his business interests and playing basketball. I think that might be about it.”

Although ‘The Last Dance’ covers many aspects of Jordan’s intriguing persona, it’s ultimately all about the sport, highlighting the grit, the determination, the competitive spirit that still burns fiercely in the eyes of this 57-year-old new grandfather.

Despite all of the marketing hoopla away from the hoop, Jordan himself knew that it was only ever about the basketball.

“My game was my biggest endorsement. Believe me, if I was averaging two points and three rebounds, I wouldn’t have signed anything with anybody,” he says.

Director Hehir says that beyond any of Jordan’s perceived character flaws, our lasting impression of the show will be of an incredible athlete willing his team to extraordinary success.

“He came into the league and he was the team’s only hope,” Hehir says. “By the end of that ’98 series, Michael has to carry the team again. If you wrote the ending to that series in the script, you’d be laughed out of a Hollywood office because it’s so corny, but it actually came true.”