As Devdas recently completed 20 years, it feels opportune to revisit this overlong, verbose, subliminal tragedy and look at its women through the lens of agency and tradition, considering how rapidly the depiction of women in Hindi films has changed since its release.

Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s magnificent period drama Devdas sure revolves around its eponymous protagonist, but much like the Baahubali films, its true glory lies with its women who continue to shine and be even as Devdas dissolves into oblivion.

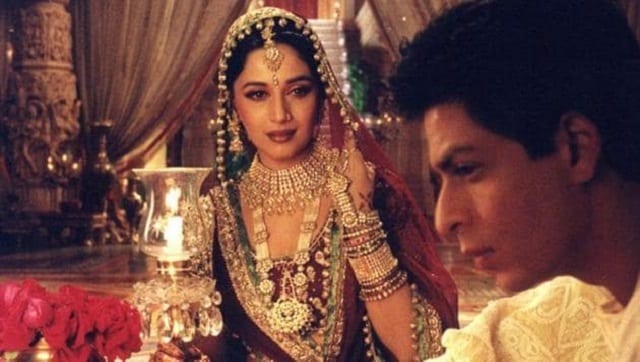

The 2002 film, based on Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s celebrated novel written about a century ago, is memorable for several reasons. The most expensive Indian film to have been made till then, it brought back the blockbuster actor-director pair (Aishwarya Rai Bachchan and Bhansali) together a second time three years after the stupendous success of their maiden outing, Hum Dil De Chuke Sanam. To titillate the audience further, Bhansali also roped in Shah Rukh Khan—the undisputed king of romance—as Dev and Madhuri Dixit as the dazzling Chandramukhi. The result? Devdas had a dream run at the box office, becoming the highest-grossing film of that year, and won five national and 11 Filmfare awards.

However, despite all the accolades and the adulation, what stands out as starkly 20 years later is its unapologetic, unabashed portrayal of feminine grit and power. Devdas is one of those rare Hindi films which allows even its supporting female characters to flourish and leave a haunting, indelible impact. On its two-decade anniversary, it feels opportune to revisit this overlong, verbose, subliminal tragedy and look at its women through the lens of agency and tradition, considering how rapidly the depiction of women in Hindi films has changed since its release.

There are several scenes of Parvati—essayed by an ethereal Bachchan—and Chandramukhi that deserve detailed, critical analysis and appreciation. However, it would be unfair to start with anybody but Kirron Kher, who plays Paro’s mother Sumitra in a career-defining performance. Kher’s act in Devdas is a masterclass, a testament to all that can be achieved if you equip a terrific actor with a visionary director and a crew that works as one with them to realize a common dream. Her Sumitra is at once vulnerable and stony stoic, uncontainable, and dreamy-eyed. Her naïve optimism and child-like enthusiasm are as contagious as her rage prophetic. Even though she’s a minor character, she dominates the first half of the film, towering over everyone else, making each frame, each dialogue, each expression her own.

It’s difficult to pick a favorite sequence in a performance as faultless as Kher’s in Devdas, but I, admittedly, do have one. Her dance in front of a hall full of people in More Piya as Paro and Dev romance on the banks of a river. Elated beyond bound at the prospect of Paro and Dev’s union, she dances with guileless abandon as though it were their wedding night. If you want to see how unbridled happiness and the fulfillment of one’s most-cherished dream looks like, you must watch Kher in this segment. And don’t just stop with the song; watch out for the scene that follows, and you’ll know what I’m talking about. It’s as much the choreography and the dialogue as it’s her, making it one of the most precious cinematic moments of all time.

She enters the party—a baby shower for Dev’s bhabhi Kumud, all heart, and blessings. But she leaves as Durga with fire in her eyes and a curse on her tongue. Thus she says, “Aayi toh thi tujhe duaaen dene ki tere ghar chand sa beta ho. Par ab toh yahi dua nikalti hai ki tera ghar bhi chandni se aabaad ho. Tere ghar bhi beti ho.” Sheer goosebumps.

Then there’s Paro. Effervescent and ethereal. The kind of beauty that no adjective can sufficiently describe. Though in love with Dev ever since they were children, she doesn’t allow him to bully her or make her feel inferior despite his high birth and London education. If the sky is his, she reigns over the land. She matches Dev’s arrogance with her pride, his cockiness with her wit. Not once in the film does she let her unflinching devotion toward him overrule her self-respect and decisiveness. Prakash Kapadia and Bhansali’s screenplay makes her walk the thin, taut line between love and respect with remarkable distinction and dignity.

In a pivotal scene, Paro visits Dev in his bedroom in the dead of the night, unafraid of society or stigma. Her brave act is a plea, a desperate cry for him to muster the courage to legitimize their relationship in the face of familial objection. Since his parents refuse to give in, Dev leaves the house in protest but makes the fatal error of not taking Paro along. He then worsens it by sending her a letter asking her to forget him and move on. When he realizes his blunder, it’s too little too late.

He finally asks her to elope with him on her wedding night when the groom’s procession is at her doorstep. Had Devdas been a film of today, Paro would have taken the plunge, shown everyone the finger, and lived the life she always wanted with the man she’d loved even before she understood what it meant. Feminists and critics would have hailed the move as a step in the right direction and lauded Bhansali for giving an old, dated story a refreshing empowering twist. But Bhansali is a purist, unwilling to reduce his heroine’s life decisions to a motivating Instagram quote.

So, instead of running away with him, Paro tells Dev, “Tumhare mata pita hain, toh mere nahi? Tumhare parivaar ki izzat hai, toh humaari nahi? Tumhare mata pita zamindaar, toh mere kuch bhi nahi?” She gets married, not to him, and in doing so, shows Dev how it feels to be left behind.

The film is peppered with several instances that establish Parvati as a lot more than a lovelorn village belle. For instance, as the young wife of a much older man, she navigates all the new equations with remarkable wit, warmth, and courage. Her first meeting with her stepson-in-law—the sly, predatory Kalibabu (Milind Gunaji) is especially noteworthy. When he outs her love for Devdas to her husband and mother-in-law, instead of trying to deny or conceal it, she accords it the honor it deserves and accepts it in all its glory, despite knowing the havoc it might wreak in her life.

Finally, there’s Chandramukhi. Dev mansplains and patronizes her for the most part of the film, telling her plainly that she disgusts him. With her, he is snarky, cruel. But Chandramukhi takes the insults in her stride and continues to care for him nevertheless as he drowns irrevocably into alcoholism and nothingness. Her light, resolute spirit shines through in her every encounter with the people around her, be it Dev, Kalibabu, or Paro. Unlike Gangubai, Bhansali’s latest iteration of a once-famous sex worker of Kamathipura, Chandramukhi isn’t proud. She takes her social and emotional ostracization as a given, an unmovable reality. But she is a product of and inhabits a different world, a starkly different time than Gangu.

When her true identity gets revealed after Dola Re Dola, I expected Paro to stand up for Chandramukhi. But even if she may not have Gangubai-style daring, Chandramukhi is no damsel in distress. “Agar aap kar sakte tamasha toh tawaifon ki zarurat hi kya thi? Uss bazaar me ek kotha aapka bhi hota,” she lashes at Kalibabu and ends her stinging, hard-hitting retaliation with a resounding, well-deserved slap across his face and inflated ego.

Though steeped in tradition and draped in finery, the women of Devdas are the kind that most filmmakers of today can praise but never create. For they are too timid, too afraid, and too obsessed with machismo to let women take center stage and sparkle. But every now and then, a Sumitra, a Parvati, and a Chandramukhi will find their way regardless. To our screens and our hearts.

When not reading books or watching films, Sneha Bengani writes about them. She tweets at @benganiwrites.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.