Forces that once attacked the secular themes in Sushant Singh Rajput’s films now seek to appropriate him

In a defining scene in Abhishek Kapoor’s Kedarnath (2018), Mansoor played by Sushant Singh Rajput attends a meeting of locals discussing the possibility of building a new hotel and other commercial establishments in the Hindu pilgrimage centre from which the film draws its title. When he suggests as an alternative that the number of devotees permitted per annum be restricted in the interests of the region’s delicate ecology, the resulting tension at the gathering is almost palpable. Mansoor is Muslim and works as a porter who transports Hindu pilgrims to the famed holy place. “Where did you land up in our midst?” he is asked by an attendee at the meeting who clearly views his intervention as an offensive intrusion. Mansoor looks surprised as he replies: “But we have always been here.”

That moment in Kedarnath is a poignant representation of the othering of India’s Muslims in a once-inclusive society, made all the more significant by the Islamophobia raging through the current public discourse and bolstered by some major recent Bollywood productions. In the weeks since Rajput’s death by suicide, you would imagine that this scene in Kedarnath would have come up repeatedly for discussion in all-pervasive celebrations of his work. It has not.

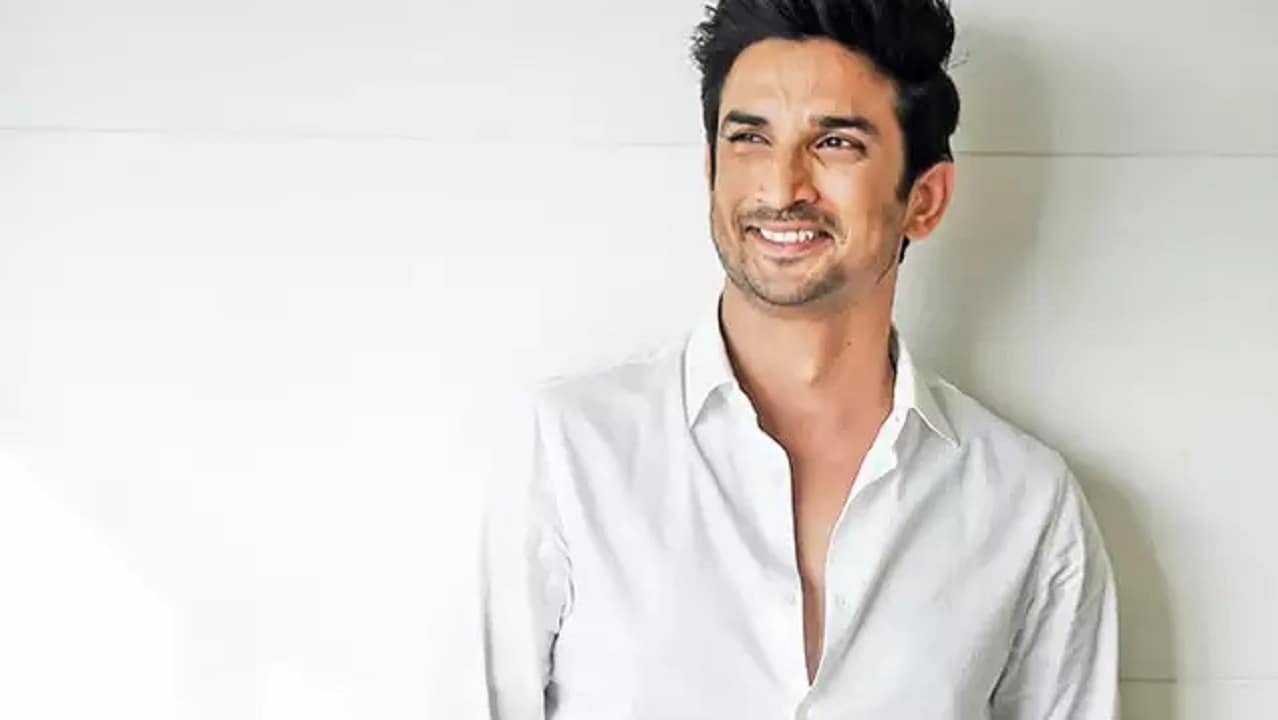

The late Bollywood actor’s interesting filmography, the lack of mental health awareness in India, depression, suicide, elitism in Bollywood, nepotism across all professions in the country, caste and class divides across Indian film industries – in a sensible society, these are the subjects that would have been seriously analysed following his demise. Instead, in an India where sensationalism takes precedence over sense, the last few weeks have passed in a whirl of noise that has done no justice to the aforementioned issues or his life and work.

In place of sobriety, what we have got is a din on social media dominated by bizarre theories about Rajput’s end, misogynistic abuse being hurled at the daughters of Bollywood stars, homophobic slurs directed at producer-director Karan Johar, Islamophobia and author Chetan Bhagat’s threat to critics who will review the actor’s last film, Dil Bechara, releasing this week. Meanwhile, the news media has been overrun with conversations by Kangana Ranaut about Kangana Ranaut’s campaign for Rajput, her own suffering as a non-star-kid trying to make it in the film industry, her heroism in calling out nepotism in Bollywood and her views on sundry female stars ranging from Alia Bhatt (daughter of actor Soni Razdan and producer-director Mahesh Bhatt) to Taapsee Pannu and Swara Bhasker (both of whom are rank outsiders like Ranaut herself).

In all this, the one entity relegated to the sidelines is Rajput himself – the real Rajput, not the myth that is now being constructed around him.

To a certain extent, this myth-building is natural – a shocked and grieving public’s inevitable response to the untimely death of a talented, successful, handsome, heartachingly young artiste. Largely though, it has been a strategic choice made by those not invested in the man as much as the purpose he now appears to serve. Since the right-wing ecosystem has turned out in full force to support one of its most famous acolytes, Ranaut, it has become necessary to mould Rajput’s past to fit their narrative. For one, the late actor’s vocal condemnation of violence and threats by the Rajput organisation, Karni Sena, in the run-up to the release of the Hindi film Padmaavat in 2018 has been brushed under a carpet of convenience: at the time, Rajput had briefly dropped his surname in protest, and as a consequence, he had been trolled mercilessly by online right-wing extremists; since his death, random trolls have floated the theory that he made this move not out of choice but under pressure from a powerful lobby within Bollywood and that he succumbed to their demands in his desperate bid to fit in.

Rajput’s stand on Padmaavat was perhaps his finest hour. The fact that it is now sought to be erased from his legacy by those who claim to speak for him, should be a warning bell about their motivations. The other inconvenient truth about the actor that has not even been a whimper in media conversations about him after his death is the recurring Hindu-Muslim equation in his filmography.

Back in 2018, BJP members in more than one state had approached the courts seeking a ban on Kedarnath, alleging that it promotes what fundamentalists call ‘love jihad’ (the term used for the reprehensible conspiracy theory that Muslim men trap Hindu women with their wiles) and insisting that it hurts Hindu sentiments with its depiction of a romance in a sacred town. The object of their ire was the central plot point of the film: an upper-caste Hindu woman called Mandakini (played by Sara Ali Khan) falling in love with Rajput’s Mansoor.

In Rajput’s brief career, this was his second screen role that had antagonised the communal/patriarchal establishment for precisely the same reason. Rajkumar Hirani’s PK (2014) had pushed the envelope into cross-border territory by casting him as a Pakistani Muslim youth called Sarfaraz who the Indian Hindu heroine, Jaggu (Anushka Sharma), falls in love with. PK offered an excellent illustration of how confirmation bias operates when you are conditioned to distrust a particular social group, and had been greeted with widespread protests for this, among other reasons.

Hindi cinema has for decades portrayed inter-community romances but Hindi filmmakers have tended to play it safe, possibly to pre-empt majoritarian wrath, by more often than not writing the woman in the relationship as the minority community member and the man as a member of the majority community. In a patriarchal society, women are seen as the property first of the family and community they are born into, with their ownership later being passed on to the family and community of the man they marry. For those who subscribe to this logic, if a woman marries out of community, she is deemed to be lost to the community of her birth – on the other hand, she and her uterus are counted as gains for her husband’s people.

Both PK and Kedarnath went against the tide. That Rajput was a common factor in both was clearly no coincidence, considering that he risked starting his Bollywood career with Kai Po Che – also directed by Abhishek Kapoor – in which his character, Ishaan, gives up everything for his Muslim protégé in Gujarat during the 2002 anti-Muslim riots.

I did not know Rajput personally, beyond one long and very illuminating meeting. I do know his films though. And the fact that a thread of Hindu-Muslim amity ran right through his Bollywood career of barely seven years, that too when Hindu-Muslim tensions in India are at an all-time high and most of his industry has been bowing before the establishment, indicates that there was far more to this young man than his self-appointed self-serving spokespersons have suggested since his death.

It is ironic that the forces who, in Rajput’s lifetime, attacked his films and his high-profile stand against his very own influential community, now seek to appropriate him in death. Ironic because the characters he played in Kai Po Che, PK and Kedarnath refused to view human beings through the lens of their religious identity. A healing example of this worldview can be found in Swanand Kirkire’s lyrics of the song ‘Chaar Kadam‘ that are sung in a scene featuring Jaggu and Sarfaraz early in PK:

Bin poochhe mera naam aur pata

Rasmon ko rakh ke pare

Chaar kadam bas chaar kadam

Chal do na saath mere

(Without asking my name or address

Setting all tradition and customs aside

Do walk a few steps

Just a few steps with me)

Find latest and upcoming tech gadgets online on Tech2 Gadgets. Get technology news, gadgets reviews & ratings. Popular gadgets including laptop, tablet and mobile specifications, features, prices, comparison.