The problem, for India, only gets compounded with the government lacking any reliable database on antiquities and their locations. Also, even as citizens, we don’t seem to fathom the real worth of our own cultural properties. Take the value of seized items from just one smuggler.

The New York-based Subhash Kapoor, according to US agencies probing the case after his arrest in 2011, was caught with contraband artefacts of Indian origin worth $100 million. As smugglers like Kapoor often deploy the tactic of replacing a real item with afake, one doesn’t even always get to know whether idols, antiques, statues, etc, taken from clearly not-so-protected heritage sites are real or fake.

In such a scenario, it is time the Union government undertakes a nationwide survey of antiques and soon-to-be antiques (items of worth aged 75-99 years) spread across the country. The process should be scientific and time-bound with participation from experts and scholars. Each item needs to be examined closely, photographed from all angles, 3Dscanned and geotagged before being listed in the official database. The system will be foolproof only if a unique identification number (UIDN) is issued against each property.

In other words, every antique item must have its equivalent of an Aadhaar number and a certificate. Such a wide-angle documentation is necessary and urgent as the loot of Indian heritage is neither just a medieval nor a colonial saga, but a happening phenomenon that is being conducted under our noses. One reason for this 21st-century pillaging of India’s heritage not grabbing headlines is because no one seems to know the extent of this loot — in other words, what is there, and what has been stolen.

A September 2022 report by the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister (EAC-PM), ‘Cultural Heritage: An Urgent Need for Protection and Preservation’ (bit.ly/ 3S0fGSt), makes a bid to portray the scale of this menace. Quoting S Vijay Kumar’s 2018 book, Idol Thief: The True Story of the Looting of India’s Temples, the report says some 1,000 pieces of ancient artworks are stolen from Indian temples annually. They are invariably shipped to the global market, ‘with only 5% of the thefts being reported’.

The 67-page report adds, ‘Every decade, close to 10,000 pieces of art, if not more, leave the shores of India undetected.’ That means India’s enforcement agencies — from a beat constable posted at a thana to customs sleuths deployed on a coastline — need to be sensitised and trained. Dharohar (Heritage): National Museum of Customs and GST, in Panaji, Goa, was founded in 2009 — and upgraded earlier this year to include a new GST/ taxation gallery — preserves some unique customs-seized items.

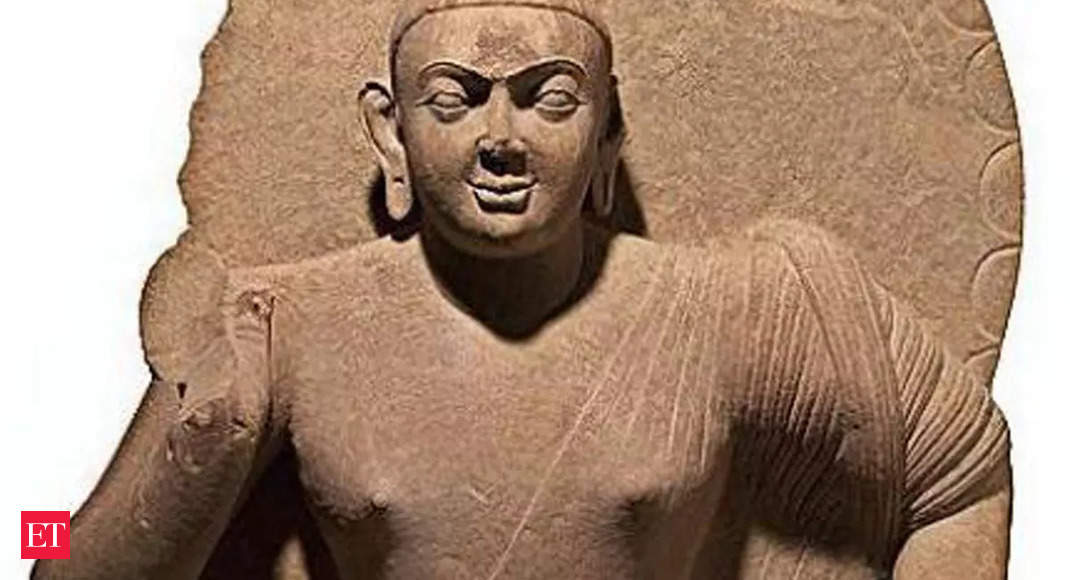

These include a 16th-century handwritten and illustrated manuscript of Abul Fazl’s Ain-i-Akbari rescued by Patna Customs at Raxaul, Bihar, on the India-Nepal border, a 12th-13th-century stone sculpture of Standing Surya recovered in Mumbai, select circa 11th-century astronomical instruments recovered by Delhi Customs, and a 16th-century metal alloy, goldplated idol of Jambhala, the Buddhist god of wealth, recovered by Gorakhpur Customs, Uttar Pradesh.

While each of the items speaks of the good job done by our enforcement agencies, the reality is that smugglers are more than often ahead of the curve, regularly dodging police and custom personnel. High-valued antiques are often even passed off as modern, home decor items. Archaic laws, lenient punishments and a gross inability to understand this multibillion-dollar contraband market and its operators and customers only help exacerbate the situation. India, of late, has been aggressively pursuing all its legal and diplomatic channels to win back some of its stolen and lost treasures.

There has also been limited success. The US government, for instance, returned 157 artefacts and antiquities of Indian origin in September 2021. But such random gains will have no meaning if we continue to lose another thousand every year. What we need is to devise better ways to deal with private collectors, auction houses and museums that trade in Indian stolen antiques. But the priority should be to first create a digital database, so that we don’t end up losing more priceless objects of our culture and heritage.