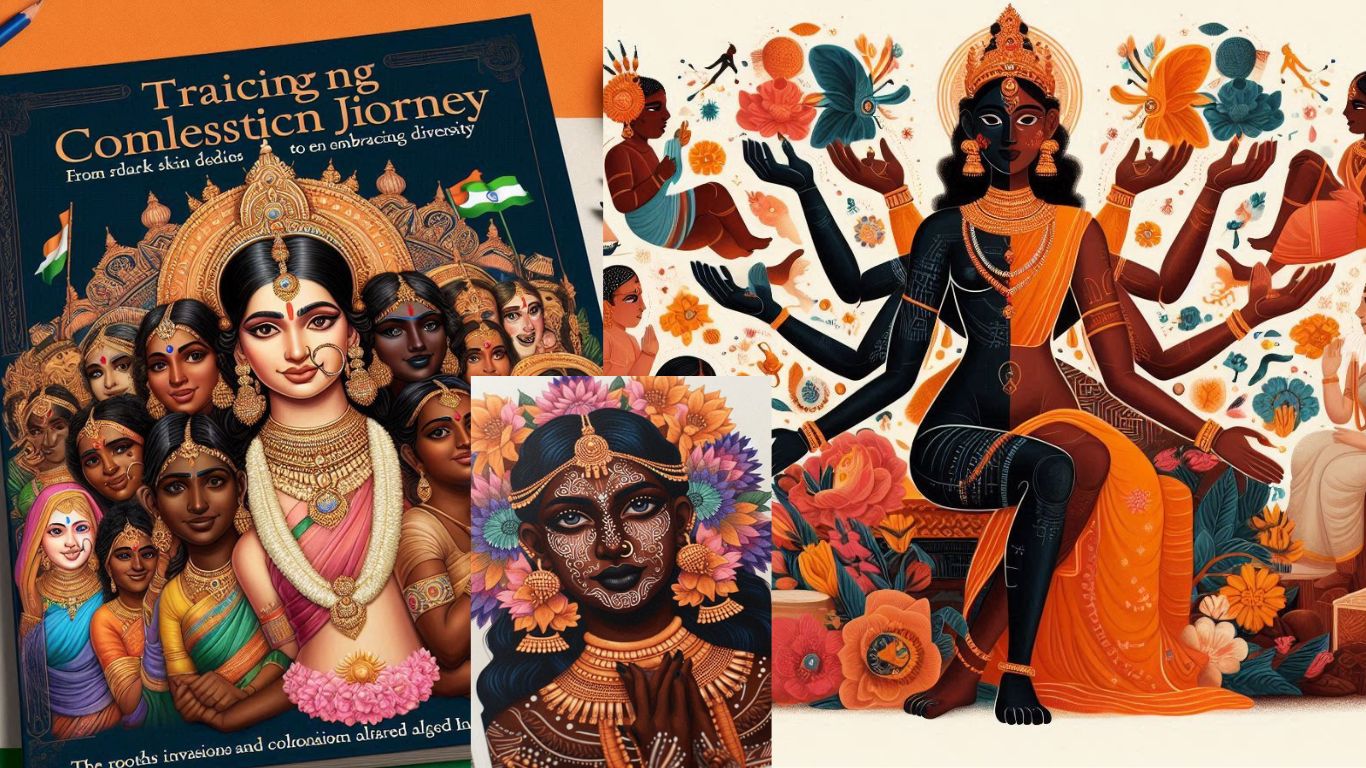

India, one of the world’s oldest and most diverse civilizations, historically embraced a vast spectrum of skin tones. Spread across various climates, India naturally developed a mosaic of physical features, from the wheatish complexions in the north to darker tones in the south. This diversity was not just accepted but revered.

Dark-skinned deities like Krishna, an incarnation of Lord Vishnu, whose name translates to “black” in Sanskrit, were celebrated as powerful and beautiful. Prabhu Shri Ram is also known to be black in color, while the goddess Kali, whose name also means “black”, represents divine strength and protection. This shows that for Indians, beauty lay in the depth of character, wisdom, and valor rather than skin color. Therefore, ancient Indians revered dark skin.

Powerful characters like Draupadi in the Mahabharata were also dark-skinned. Even the god Shiva, who wore dark ash, represented ideals that were more than skin deep. It was a norm that beauty, divinity, and strength could shine in any shade, making colorism a foreign concept in early India. In contrast to other parts around the world, in Vedic India, dark skin was not a shame, it was a blessing.

Even in our art and paintings in different parts of India, such as those found in the Ajanta, Ellora, Bagh caves, etc, one can witness the depiction of primarily dark skin if not all shades of skin tone.

The Arrival of Turks, Persians, and Arabs

This inclusive attitude toward skin color began to shift with the arrival and invasion of Turks such as Mahmud of Ghazni, Persians, and Arabs in the 8th century. Though India had long seen foreign traders and visitors, the invasions brought a new cultural influence from Persia and the Arab world, where light-skinned beauty ideals were already prevalent. Persian literature, which idealized fair-skinned protagonists, became part of the courtly culture and influenced the Indian nobility.

Persian poets who entered not-so-fair India described fair skin as a marker of beauty and elegance. These depictions began to influence the ideals of Indian courts, and admiration for lighter skin slowly crept into Indian society. Over time, the preference for fair-skinned heroes and heroines in literature and art subtly introduced a new bias. The ruling class, which was often fairer-skinned, came to be associated with beauty, power, and desirability.

The works of Rumi, Amir Khusrau, and other so-called-“great poets” offer a glimpse into the deeply entrenched colorism and racial hierarchies that were woven into the fabric of Persian and Islamic literature. These poets, celebrated for their “spirituality”, also perpetuated intolerance against darker-skinned peoples and attached negative connotations to particularly Indians.

Rumi, in his Masnavi, draws a stark distinction between “white” and “black” faces, using these racial markers as symbols of purity and disgrace. In one troubling verse, he writes:

“On the Day when faces shall become white or black,

Turk and Hindi shall become manifest from among that company.

In the womb of this world, Hindoo and Turk are not distinguishable,

But when each is born (into the next world), each appears as glorious or miserable.”

In these lines, the racialized language is very clear. The “black” face of the Hindu represents one who will be disgraced, while “white” faces align with purity. As one can see, Rumi’s verses reinforce the superiority of whiteness.

Annemarie Schimmel, in The Triumphal Sun, further explores these prejudices within Persian literature, pointing out the frequent descriptions of Hindus as “lowly and ugly,” while black-skinned Zanji were often seen as “cheerful,” yet naïve and ignorant of their inferiority. Schimmel writes:

“The Hindu is usually described as lowly and ugly. The zanji, Negro, black-faced like him, is generally a model of spiritual happiness… While the Turks, Hindus, and Zanji’s belong to the general stock of classical Persian imagery…the use of color symbolism in Persian poetry reinforces a deeply ingrained hierarchy.”

Amir Khusrau, tragically known as the “Parrot of India,” similarly invoked racial superiority and portrayed Indians as inferior to lighter-skinned Muslims.

These figures, through their influential works, were instrumental in creating and spreading colorist ideologies that continued through the Mughal era and were later solidified by British colonizers. This marked the early stages of colorism in India.

The Mughal Influence

The Mughal Empire, in the 16th century, brought with it the same Persianized version that established these biases. Mughal emperors like Akbar and Jahangir were fascinated with Persian aesthetics, which held fair skin in high regard. While the Mughals had a preference for fair-skinned individuals in their courts.

The elite circles of the Mughal court began to associate lighter skin with nobility and sophistication, a sentiment that trickled down to the broader society. This association was reinforced through literature, paintings, and even matrimonial preferences within the noble classes. Gradually, dark-skinned figures in Islamic Indian paintings were replaced, leading to an overwhelming presence of white-skinned individuals. This trend is also observed in Hindu paintings, where dark-skinned figures became increasingly absent.

This shift occurred because Hindu elites in business with the Mughals began to patronize lighter-skinned representations, which might be because of the shame surrounding darker skin. Moreover by promoting fair-skinned courtiers, dancers, and even concubines as the epitome of beauty. This preference began to spread beyond the royal court, eventually affecting social hierarchies and marriage practices in wider Indian society.

The British Raj

While Islamic rulers preferred lighter skin, Europeans took this notion of superiority to an entirely different level. Beginning with the Portuguese, who sought to convert Indians to Christianity, the “saint” Francis Xavier expressed his disdain for Indians due to their darker skin.

In a letter to the Society of Jesus in Rome, he wrote, “For as there is so great a variety of color among men, and the Indians being black themselves consider their color the best, they believe that their gods are black. On this account, the great majority of their idols are as black as can be, and moreover are generally so rubbed over with oil as to smell detestably, appearing as dirty and horrible to look at.” Ironically, this man has more than 100 schools and educational institutions in India named after him.

When the British colonized India in the 17th century, they brought a deeply entrenched belief in white supremacy. The British considered themselves not only racially but also intellectually and morally superior to the “dark-skinned natives” they ruled. The establishment of “White Towns” for British settlers and “Black Towns” for Indian natives was one such example. White skin became synonymous with privilege and status, while brown skin was associated with servitude and inferiority.

British propaganda reinforced these racial divides. Schools, public spaces, and institutions were marked by discriminatory signs that openly declared, “Indians and dogs not allowed.” It was clear that the British regarded their lighter skin as a divine mandate to rule over those with darker complexions.

Figures like Winston Churchill openly despised Indians, dismissing them as “a beastly people with a beastly religion.” This disdain was mirrored in the literature of the time.

Rudyard Kipling, for instance, spoke of the “white man’s burden” to “civilize” India, casting Indians as lesser beings needing British governance to “lift” them from savagery. British literature is filled with the word – ‘fair’ which, showcases their single-minded obsession with the standard of beauty.

Over time, along with the fabricated Aryan invasion theory and similar ideas, the British established a caste and racial hierarchy, dividing society along their narrative of higher castes being fair-skinned and lower castes being dark. “Fairness” became a ticket to power and social mobility, a trend that has profoundly impacted Indian society to this day. In some states, especially Tamil Nadu, the debate over who is more Indian continues.

Colorism in Modern India

After nearly two centuries of British rule, India gained independence in 1947, but the legacy of colorism continued to haunt Indian society. The social hierarchy that equated lighter skin with superiority was so deeply ingrained that it persisted even after the colonialists left. Indian society, influenced by generations of colonial dominance, had internalised the British standards of beauty, associating fair skin with power, and success.

This colonial hangover continues to manifest in modern India, where fairness creams are still dominating the beauty industry. Advertisements perpetuate the idea that “fair is beautiful,” often depicting foreign lighter-skinned models as successful, confident, and attractive. Bollywood, one of India’s most influential cultural exports, has always cast fair-skinned actors in lead roles, sending a message that fair skin is not only desirable but essential for success. Fair-skinned actors dominate, while darker-skinned individuals are frequently limited to villainous roles or stereotyped as rural and backward.

The pursuit of fair skin has driven many Indians to adopt practices such as skin bleaching, a phenomenon referred to as “bleaching syndrome.” This phenomenon is not unique to India; it exists in other countries with colonial histories, like those in Africa and Southeast Asia, where skin bleaching has become a means of achieving social acceptance and “respect.”

Breaking the Chains

There has been some resistance to this obsession with fairness. In 2013, the activist group Women of Worth launched the “Dark is Beautiful” campaign, endorsed by actress Nandita Das, to celebrate dark skin tones. Bollywood actor Nawazuddin Siddiqui also spoke out against the industry’s “racist” preference for fair-skinned actors.

Colorism in India remains a legacy of colonial oppression and foreign invasion, an unfortunate example of how deeply rooted biases can persist long after their origin. However, India is slowly tracing back to its roots, as the stone used to create the 51-inch Ram Lalla idol is special black granite. The beauty and essence of the idol serve as a reminder that Indians are those who once worshipped darker-skinned gods, not pale lords.