Autumnal-wintry love stories are like bitter chocolate. You have to have a taste for it. Indian cinema is yet to get a hang of it. Attempts to do films about older people in love have been negligible in our films, if not entirely farcical. Something as near-flawless as Max Walker-Silverman’s A Love Song is not only impossible in India but unattainable?

Why ? Because the two aging protagonists, Faye and Lito, played by the amazing Dale Dickey and Wes Studi, are shown to have a night of physical pleasure even though they are way past the age of consent.

People above 60 are not supposed to have sex in India. I say this with a straight face. Parents in bed doing anything beyond talking is not allowed.

Here in A Love Song, Faye is alone camping in the Colorado wilderness, captured by Mexican cinematographer Alfonso Herrera Salcedo in all its tranquility and splendour. There are long stretches of pregnant silences in the film: Faye is alone for a major part of the film. Before Lito arrives, she has a couple of very revealing encounters, one with a family of local American Indians of all men, and one little girl who amusingly, talks on the men’s behalf, and also Faye meets a two Black women who are lesbian lovers and are not sure whether they want to be together for a lifetime.

Then the man Faye has been waiting for—technically for some weeks but actually much much longer—arrives. Their encounter is clearly a shared event they have waited for most of their lives. There is not much to say. Faye is not much of a talker. The shared silences are exquisitely eloquent. A Love Song is one of those rare romances that do not fear silences.

A still from A Love Song

What would the love in Franco Zeffirelli’s Romeo & Juliet be without Nina Rota’s music? What would A Love Song be with any kind of background music? There is a silence at the soul of this masterpiece which remains inviolable, non-negotiable to the end. For most of this all-too-brief romantic treasure Dale Dickey’s Faye is shown waiting. She scans the horizon with her still-bright eyes, hopes that the car in the distance will stop at her trailer which is home for her.

Dale Dickey is so comfortable in her solitary environment, it feels like she has lived there all her life. The actress, who is 61, actually looks a lot older in A Love Song. The wizened face and the eyes of one who has seen so much life that she doesn’t need to see anything more, haunted me way past the film. It’s the eyes of one who knows life is all about hoping, waiting. This is a deceptively calm placid film. Its surface silences secrete a universe of turmoil. Just like all great cinema is supposed to.

Dale Dickey

Gaspar Noe’s French melancholic meditative masterpiece Vortex is the kind of cinema that one can neither embrace nor reject. It merits our deepest respect and attention and yet its theme and treatment of old age and mortality is depressing and sickening, though not in an undesirable way. This is an autumn sonata on autumnal solitude that Ingmar Bergman could have made were he not so fixated on romancing existentialism.

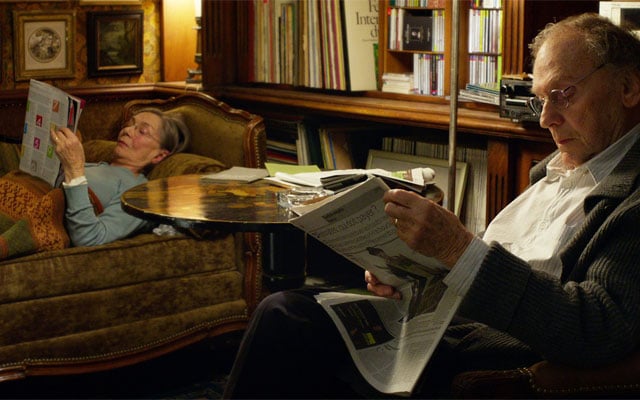

Vortex

There is nothing even remotely romantic about Vortex. The old couple in the film, played with excruciating believability by two veteran actors I don’t recall seeing before, Dario Agenta and Françoise Lebrun, go about the business of ….well, of being old, and whatever it entails, with no dramatic troughs to make themselves interesting to the audience. Come to think of it, I have not seen a more audience-unfriendly film in my life.

It’s not that writer-director Gaspar Noe has no respect for his audiences’ sensitivities. It is the other more urgent perspective that emerges from the debris of approaching death, which concerns Noe more. There is none of the glorious romanticism of that other French masterpiece Amor on wintry introspection, that made the film so achingly enticing.

In Vortex, most of the lengthy two-hour-plus screen time is taken up by the the fading couple, one of them walking from room to room aimlessly looking for something, anything, to occupy the sinking mind; the other making notes to write a book on dreams in cinema that he knows he would never be able to make.

Noe splits the screen all across the storytelling into two so that we see the old woman and the old man in the same house living two separate lives, almost two independent states of being disconnected from the world outside.

Most films about wintry desolation show the old couple huddling together in a loving embrace waiting for the end to strike them. Vortex shows how disconnected two dying souls no matter how close, become separated by their individual illnesses, phobias and dementia.

Strangely the entire film is shot in a split screen, with the old man, relatively in better health, occupying one-half of the screen, and the frail old woman, suffering from terrifying dementia, occupying the other. The writer-director, in an interview, explained the reason for the split screen: “Two separate screens telling the interlinked lives of these two members of a normal couple who live under the same roof but are disconnected by some mental disease.”

I hear you. But I am not convinced that the split screen is the best method to describe quarantined desolation. The format becomes especially awkward when the couple’s son (Alex Lutz) shows up in the untidy house with his own little son and serious marital problems. The screen becomes divided not only by its format but also in the individual clingy love the two old people feel for their son.

This is not shared love. It is scared love. Throughout the lengthy atrophied journey of two lost souls sharing the same roof, I felt a sense of growing gnawing feeling of dread and doom. Vortex is not meant to make us feel good about life. But then again, it is not aimed at making us feel miserable about old age either.

Somewhere, deep down in its profound rumination on life death and, whatever lies in-between, Vortex finds the core of immortality. All our adult lives we dread death.When it is finally coming we are just not looking at the approaching end. Vortex gives us a view of what lies underneath the dynamics of death.

A still from Vortex

Michael Lembeck’s Queen Bees is also a meditation on mortality, albeit one that is severely deprived of subtlety and stymied by stock situations and characters. Though the cast is impressive it isn’t a pleasant experience to see the great Ellen Burstyn (remember her magnificent Oscar-winning performance in Alice Doesn’t Live Here Any More?) and the one-time sex symbol Anne Margaret playing octogenarians. It took me a while to recognize the slouching old man who plays Burstyn’s love interest. It was none other than James Caan, his last film before death, the rebellious Corleone son in The Godfather, a faint replica of his fiery self.

Queen Bees film

To see this once young and charismatic cast reduced to a wintry wispy shadow of the past is heartbreaking, much more than the film which tries to be a cheerful treatise on the old and ends up looking like an evening for the old where the veteran cast tries to have fun with numbers. Burstyn is Helen who lives all alone and can’t get along with her daughter Laura (Elizabeth Mitchell). The daughter admittedly comes across as a bit of a party pooper, much to Helen’s (and ours) annoyance. Helen must be moved to an old folks’ home when her own residence needs repairs. She would rather stay with strangers than with her own child. (I can see many parents empathizing with that). The rest of the film is an over-cute under-cooked autumnal poolside party with wheelchairs replacing pool chairs.

A unique French film Amour, featuring two 80-plus actors in the lead is a masterpiece in every sense. Austrian director Michael Haneke’s Amour is the story of Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva). Married for 50 years their comfortable life of secluded serenity in a cozy apartment in Paris is torn apart when Anne suffers a paralytic stroke. The film graphically portrays Anne’s rapid utterly dismaying descent into completely physical degeneration rendering her almost to a vegetable state, and Georges’ relentless and unwavering efforts to look after the woman whom he has loved unflinchingly for a 50 years.

A still from Amour

It’s arguably the most heartbreaking love story ever filmed because it ends with Georges snuffing Anne’s life out, putting her out of her wretchedly undignified state of helplessness. Director Haneke uses the screen space to create an idyllic life stripped cruelly of its magical quality by ill health. The camera lingers with unflinching cruelty on each moment of Anne’s pain and misery as Georges attempts to come to terms with a life of bleak companionship with a woman who can no longer share his life.

A sequence like the one where Georges picks up Anne from the bed and puts on the wheelchair is shot in one excruciating take. The camera remains frozen in its track, and the task of putting his loved one in a sitting position becomes almost an Olympian feat.

By the time this deeply mournful film reaches its devastating dead-end we know every corner of Georges and Anne’s well-appointed apartment in Paris, as well as we know every nook of their heart. The film leaves us Indian moviegoers with many urgent questions. As a nation that owes opulent allegiance to traditional values of compassion, loyalty, unstinted devotion and honesty in marriage why don’t we make films like Amour?

Subhash K Jha is a Patna-based film critic who has been writing about Bollywood for long enough to know the industry inside out. He tweets at @SubhashK_Jha.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.