RCGS

RCGSWreck hunters have found the ship on which the famous polar explorer Ernest Shackleton made his final voyage.

The vessel, called “Quest”, has been located on the seafloor off the coast of Newfoundland, Canada.

Shackleton suffered a fatal heart attack on board on 5 January 1922 while trying to reach the Antarctic.

And although Quest continued in service until it sank in 1962, the earlier link with the explorer gives it great historic significance.

The British-Irish adventurer is celebrated for his exploits in Antarctica at a time when very few people had visited the frozen wilderness.

“His final voyage kind of ended that Heroic Age of Exploration, of polar exploration, certainly in the south,” said renowned shipwreck hunter David Mearns, who directed the successful search operation.

“Afterwards, it was what you would call the scientific age. In the pantheon of polar ships, Quest is definitely an icon,” he told BBC News.

The remains of the ship, a 38m-long schooner-rigged steamship, were discovered at the bottom of the Labrador Sea on Sunday by a team led by The Royal Canadian Geographical Society (RCGS).

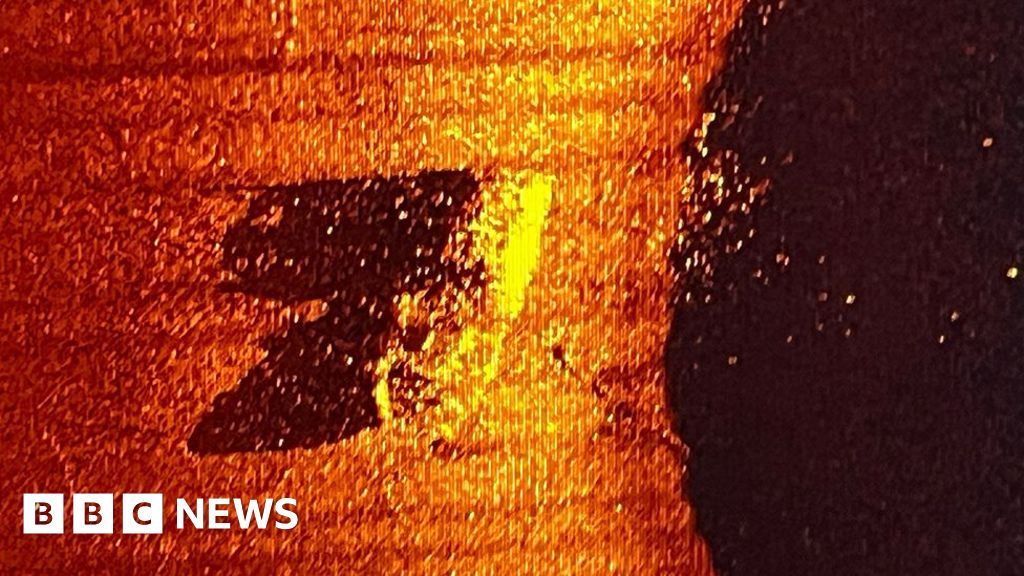

Sonar equipment found it in 390m (1,280ft) of water. The wreck is sitting almost upright on a seafloor that has been scoured at some point in the past by the passing of icebergs.

The main mast is broken and hanging over the port side, but otherwise the ship appears to be broadly intact.

Quest was being used by Norwegian sealers in its last days. Its sinking was caused by thick sea-ice, which pierced the hull and sent it to the deep.

The irony, of course, is this was the exact same damage inflicted on Shackleton’s Endurance – the ship he used on his ill-fated Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914–1917.

Fortunately, the crews of both Endurance, in 1915, and Quest, in 1962, survived.

Indeed, many of the men who escaped the Endurance sinking signed up for Shackleton’s last polar mission in 1921-1922, using Quest.

His original plan had been to explore the Arctic, north of Alaska, but when the Canadian government withdrew financial support, the expedition headed south in Quest to the Antarctic.

The new goal was to map Antarctic islands, collect specimens and look for places to install infrastructure, such as weather stations.

Shackleton never made it, however, struck down by heart failure in the Port of Grytviken on the British Overseas Territory of South Georgia, the last stop before reaching the White Continent. He was just 47 years old.

After his death, Quest was involved in other important expeditions, including the 1930-31 British Arctic Air Route Expedition led by British explorer Gino Watkins, who himself tragically died aged 25 while exploring Greenland.

Quest was also employed in Arctic rescues and served in the Royal Canadian Navy during WWII, before being turned over to the sealers.

The RCGS team members carried out extensive research to find Quest’s last resting place. Information was gathered from ships’ logs, navigation records, photographs, and documents from the inquiry into her loss.

The calculated sinking location in the Labrador Sea was pretty much spot on, although the exact co-ordinates are being held back for the time being.

A second visit to the wreck, possibly later this year, will do a more complete investigation.

“Right now, we don’t intend to touch the wreck. It actually lies in an already protected area for wildlife, so nobody should be touching it,” associate search director Antoine Normandin said. “But we do hope to go back and photograph it with a remotely operated vehicle, to really understand its state.”

Alexandra Shackleton is the explorer’s grand-daughter, and was patron to the RCGS survey.

“I was thrilled, really excited to hear the news; I have relief and happiness and a huge admiration for the members of the team,” she told BBC News.

“For me, this represents the last discovery in the Shackleton story. It completes the circle.”

The explorer continues to spark interest more than a century after his death.

Hundreds of people visit his grave on South Georgia every year to pay their respects to the man known by his crews simply as “The Boss”.

“Shackleton will live forever as one of the greatest explorers of all time, not just because of what he achieved in exploration but for the way he did it, and the way he looked after his men,” said David Mearns.

“His story is timeless and will be told again and again; and I’m just one of many disciples who’ll keep telling it for as long as I can.”

Additional reporting by Rebecca Morelle and Alison Francis