Jonathan Amos,Science correspondent, @BBCAmos

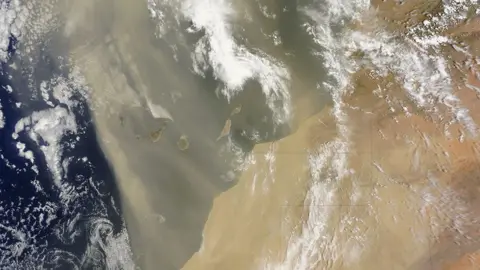

Esa

EsaA sophisticated joint European-Japanese satellite has launched to measure how clouds influence the climate.

Some low-level clouds are known to cool the planet, others at high altitude will act as a blanket.

The Earthcare mission will use a laser and a radar to probe the atmosphere to see precisely where the balance lies.

It’s one of the great uncertainties in the computer models used to forecast how the climate will respond to increasing levels of greenhouse gases.

“Many of our models suggest cloud cover will go down in the future and that means that clouds will reflect less sunlight back to space, more will be absorbed at the surface and that will act as an amplifier to the warming we would get from carbon dioxide,” Dr Robin Hogan, from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, told BBC News.

The 2.3-tonne satellite was sent up from California on a SpaceX rocket.

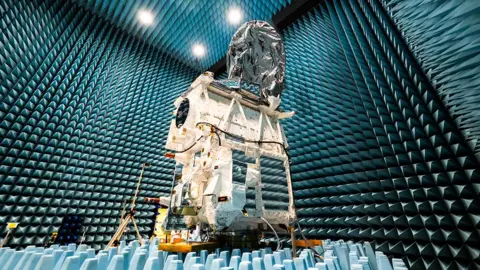

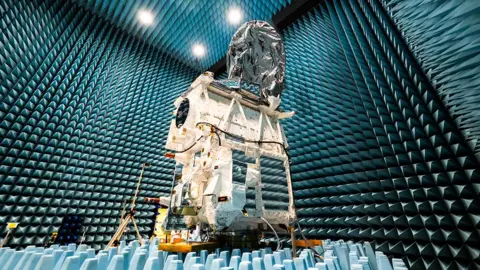

The project is led by the European Space Agency (Esa), which has described it as the organisation’s most complex Earth observation venture to date.

Certainly, the technical challenge in getting the instruments to work as intended has been immense. It’s taken fully 20 years to go from mission approval to launch.

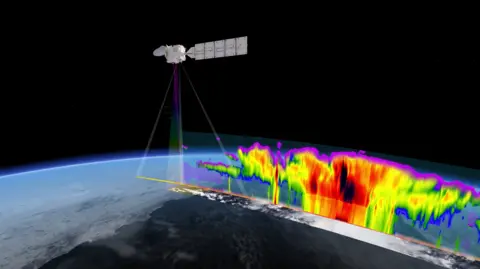

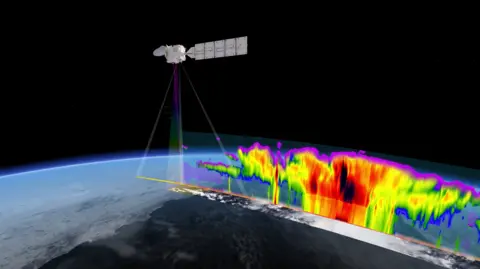

Earthcare will circle the Earth at a height of about 400km (250 miles).

It’s actually got four instruments in total that will work in unison to get at the information sought by climate scientists.

The simplest is an imager – a camera that will take pictures of the scene passing below the spacecraft to give context to the measurements made by the other three instruments.

Earthcare’s European ultraviolet laser will see the thin, high clouds and the tops of clouds lower down. It will also detect the small particles and droplets (aerosols) in the atmosphere that influence the formation and behaviour of clouds.

The Japanese radar will look into the clouds, to determine how much water they are carrying and how that’s precipitating as rain, hail and snow.

And a radiometer will sense how much of the energy falling on to Earth from the Sun is being reflected or radiated back into space.

“The balance between this outgoing total amount of radiation and the amount coming in from the Sun is what fundamentally drives our climate,” said Dr Helen Brindley from the UK’s National Centre for Earth Observation.

“If we change that balance, for example by increasing greenhouse gas concentrations, we reduce the amount of outgoing energy compared to what’s coming in and we heat the climate.”

As well as the long-term climate perspective, Earthcare’s data will be used in the here and now to improve weather forecasts. For example, how a storm develops will be influenced by the initial state of its clouds as they were observed by the satellite days earlier.

The original science concept for Earthcare was put forward by Prof Anthony Illingworth, from Reading University, and colleagues in 1993.

He said it was a dream come true to see the satellite finally fly: “It’s been a long and challenging journey with an amazing team of dedicated scientists and engineers from the UK and abroad. Together, we’ve created something truly remarkable that will change the way we understand our planet.”

One of the key technical struggles was the space laser, or lidar.

Developer Airbus-France had a torrid time arriving at a design that would reliably work in the vacuum of space. A fundamental re-configuration of the instrument was needed, which not only resulted in delay but added significantly to the eventual cost of the mission, which today is valued at some €850m (£725m).

“These aren’t missions that you put up to be cheap and quick, to solve small problems; this is complex. The reason Earthcare has taken so long is because we want the gold standard,” said Dr Beth Greenaway, the head of Earth observation at the UK Space Agency.

Earthcare won’t have long to gather its data. Flying at 400km means it will feel the drag of the residual atmosphere at that altitude. This will work to pull the satellite down.

“It’s got fuel for three years with the reserve of another year. It’s basically lifetime-limited by its low orbit and the drag there,” said Esa’s Dr Michael Eisinger.

The industrial development of Earthcare was led by Airbus-Germany, with the basic chassis, or structure, of the spacecraft built in the UK. Britain also supplied the radiometer, from Thales Alenia Space UK, and the imager, from Surrey Satellite Technology Ltd. GMV-UK has prepared the ground systems that will process all the data.

The Japanese space agency (Jaxa), because of its strong interest in the mission, will follow its usual practice of giving the spacecraft a nickname – “Hakuryu” or “White Dragon”.

In Japanese mythology, dragons are ancient and divine creatures that govern water and fly in the sky. This year, 2024, also happens to be the Japanese Year of the Dragon, known as “tatsu-doshi”.

There’s a connection in the appearance of the satellite, too, which is covered in white insulation and has a long, trailing solar panel, resembling a tail.

“Earthcare, like a dragon rising into space, will become an entity that envisions the future for us,” said Jaxa project manager Eiichi Tomita.