NOC

NOCBattling choppy waves and high winds, three engineers pulled ashore a yellow submarine in Scotland this week.

With sheets of water pouring from its body, the UK’s most famous robot – Boaty McBoatface – was winched up after 55 days at sea.

“It’s a bit slimy, and ocean smells have seeped in. There’s a few things growing on it,” says Rob Templeton, now dismantling the 3.6m robot in Leverburgh, on the Isle of Harris.

Boaty has completed a more-than-2,000km scientific odyssey from Iceland that could change what we know about the pace of climate change.

It was hunting for marine snow – “poo, basically” in the words of one researcher. This refers to tiny particles that sink to the ocean floor, storing huge amounts of carbon.

The deep ocean, referred to as the “twilight zone”, is enormously mysterious. Acting as the eyes and ears of the scientists, Boaty went there on the longest journey yet for its class of submarine. BBC News had exclusive access to the expedition.

The public originally picked the name Boaty McBoatface for a polar ship in 2016. That didn’t happen, but instead the name was quietly given to a fleet of six identical robots at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton.

This latest epic trip from Iceland was a major engineering test. “Boaty has absolutely passed. It’s a massive relief,” says Rob.

It has been an around-the-clock operation, with the engineers sending text messages to the robot via satellite. “We tell it dive here, travel there, turn on that sensor,” he says.

It is exciting technology but the science that Boaty was doing could be part of a game-changer in how scientists understand climate change.

They want to understand something called the biological carbon pump – a constant and huge movement of carbon inside the oceans.

Tiny plants that absorb carbon grow near the ocean’s surface. Animals, often microscopic, eat the plants and then poo. Those particles – the marine snow – sink to the ocean floor. That keeps the carbon locked in and reduces the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, one of the drivers of human-induced climate change.

But that carbon pump is still largely a mystery to scientists. And they are deeply concerned the warming of our oceans caused by climate change is disrupting that cycle.

Packed with sensors and instruments in its belly, Boaty turned into a mobile lab to help the scientists.

Cruising at 1.1metres per second and diving thousands of metres, Boaty had more than 20 sensors monitoring biological and chemical conditions like nutrients, oxygen levels, photosynthesis and temperature.

It is all for a major research project called BioCarbon, run by the National Oceanography Centre, University of Southampton and Heriot-Watt in Edinburgh.

I spoke to two of the scientists, Dr Stephanie Henson and Dr Mark Moore, when they were at sea in Iceland in June on the project’s first cruise.

Skies were clear and the water glistened, making conditions perfect for dropping instruments hundreds of metres down and hauling up traps filled with sediment or microscopic marine life.

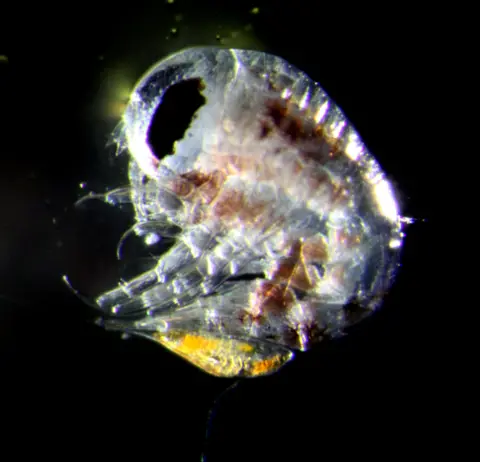

“We are measuring what’s been happening in the upper ocean with the phytoplankton, the plants that grow there. We are looking at the little zooplankton, the animals that eat them. And we’ve been measuring the fecal pellets, the poo that the animals produce,” Stephanie explained.

“Our climate would be significantly warmer if the carbon pump wasn’t there,” Stephanie said.

Without it, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels would be about 50% higher, she says.

But current climate modelling does not get the carbon pump right, she says.

“We want to know how strong it is, what changes its strength. Does it change from season to season, and year to year?” she says.

The waters off Iceland attract huge amounts of plant and marine life in spring, making it ideal for scientists to test how life interacts with carbon dioxide, explains Mark.

There are tentative signs from the research that the carbon pump might be slowing down, the scientists explain. The team recorded much smaller “blooms” of the tiny plants and animals that feed on them than they expected in spring.

“If that trend were to continue in future years it would mean the biological (carbon) pump could be weakening which could result in more carbon dioxide being left in the atmosphere,” Stephanie said.

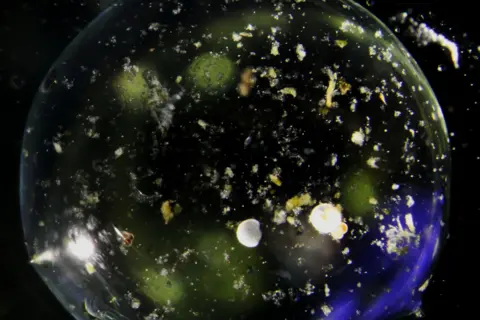

In the months to come, they will be processing their results – they have already shared some initial images of the amazingly tiny life seen under the microscope.

They hope their work will feed into the huge climate models that predict how and when global temperature will rise, and which places will be most affected.

Dr Adrian Martin, who is running the BioCarbon project, explains the research aims to better understand how the oceans are storing carbon because of a controversial field of study called geoengineering.

Some scientists and entrepreneurs believe we can artificially change the ocean, for example by altering its chemistry, in the hope it would absorb more carbon. But these are still very experimental and have lots of critics. Opponents worry geoengineering will do unexpected harm or not address climate change quickly enough.

“If you’re going to make interventions that could be global disturbances of the ocean ecosystem, you need to understand the consequences. Without that, you are not informed to make that decision,” he says.

With the first phase of the research over, Boaty is on its way home to Southampton.

In a few weeks the scientists will go back to Iceland – to compare life there in spring to the autumn.

Their discoveries could mean we better understand how our warming planet will change and find solutions to limit the damage.

Additional reporting by Gwyndaf Hughes and Tony Jolliffe