The grunt of a bowler’s delivery, the shuffle of the batsman’s feet and the crunch of willow striking leather.

These sounds – which often go unnoticed by cricket fans – are all that are needed for commentator Dean du Plessis to relay what is happening to his audience.

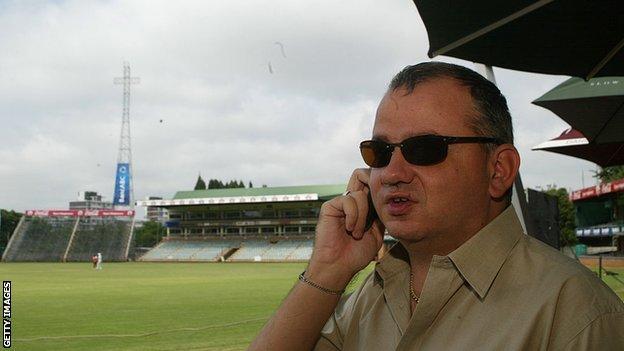

The 44-year-old Zimbabwean, who was born with tumours behind both retinas, is the first visually impaired commentator to cover international cricket.

“Commentating by sound is nothing spectacular,” he modestly says.

“I have a feed from the stump microphone, no other technology, and just listen very, very carefully; as much as sighted people pay close attention to what they’re seeing, that’s what I do.”

Speaking to BBC Sport, Du Plessis explains the origins of his love for cricket, his journey into the commentary box and the techniques he uses when calling the action.

Falling in love through the sound of cricket

Du Plessis is true cricket aficionado, whose commentary is often complemented with the most obscure statistics from years gone by.

But he was not always a fan of the sport.

“My brother Gary was a very, very good cricketer but I didn’t understand the game when I was young,” he says.

“Nobody really took time out to explain cricket to me and I actually hated and loathed that with a passion.”

Born in Harare, Du Plessis later went to study at boarding school in South Africa which is where his attachment to cricket first surfaced.

In 1991, South Africa travelled to India in what was their readmission to international cricket with the country’s apartheid regime coming to an end.

“I was listening to the third match of the series on Radio 2000, South Africa’s equivalent to Test Match Special,” Du Plessis says.

“All I heard was noise, that’s all I can describe, it was just a sound of about 60 or 70,000 Indian fanatics cheering and also continuously letting off fireworks.

“And vaguely through the noise of cheering and fireworks far away, you could hear a commentator trying to tell you what was going on and I didn’t understand what he was saying.

“It was something like ‘in comes Donald to Tendulkar, through square leg, past the umpire, down to backward square leg, the fielder picks up and they run through for a single’.

“I knew little bits about cricket but I didn’t know about backward square leg and things like that.

“But I started to listen and really enjoy it. I don’t know why because I didn’t understand what they were saying, but every time it went for four or a six, I could feel the excitement building.”

Phoning cricket stars and ‘being a pest’

As Du Plessis’ affection for the game grew, he set off on a mission to reach out to his new-found heroes.

While the modern sports fan may direct message Ben Stokes or tag Jofra Archer, Du Plessis would quite simply search for Zimbabwe cricketers in the local telephone directory.

“I would then have their number and phone using a call box from school, hoping my money wouldn’t run out and just wanting to talk cricket with these players,” he says.

“I was a real pest and the main poor victim was bowler Eddo Brandes, he was a chicken farmer and sometimes I would call him after I had finished school at 8pm and he had to literally be up with the chickens at three or four o’clock in the morning.

“He’d be a bit grumpy at first but once he was up and awake he was very, very willing to chat. I also used to phone Alastair Campbell who was very kind to me as were both the Flower brothers, Grant and Andy.”

But it was former Zimbabwe batsman David Houghton – now head coach at Derbyshire – who Du Plessis really struck up a friendship with.

“Dave was just a fountain of information, but what I really appreciate was he didn’t just answer my questions but he would ask all about me too,” adds Du Plessis.

“Once my money was about to run out and he asked for my number to call me back, and we spoke for a good 20 minutes.”

From fan to commentator

Having finished his studies, Du Plessis returned to Zimbabwe with a network of superstar cricket friends.

“It was the cricketers – the Flower brothers, Houghton, Campbell, Brandes – that made me feel very, very welcome and would invite me to come watch them play,” he says.

Du Plessis soon became a regular at national grounds and, having been given the freedom to walk around the media centres, was rubbing shoulders with broadcasters and cricket press.

During an international triangular series between Zimbabwe, India and West Indies in 2001, he was invited to join journalist Neil Manthorp, who was on old school friend, and former India batsman Ravi Shastri for a 15 minute chat on the Cricinfo website’s online radio broadcast.

Du Plessis’ knowledge and enthusiasm impressed both the broadcast team and those back at headquarters.

“It was meant to just be a short conversation on my enjoyment of cricket but Neil received an email from the office halfway through,” he says.

“The producers wanted to keep me on for the full 30 minutes and make sure I was a part of the rest of the series.

“And that’s pretty much how my commentary started. I then got my first television gig two years.”

How does he do it?

Du Plessis is often asked how he manages to identify what is happening on the field.

“Well, I don’t have any extra technology or extra stump mic or anybody telling me what’s going on,” he answers.

“I can tell you who the different bowlers are by the way they approach the crease.

“With Stuart Broad, for example, there’s a bit of a dragging sound as the ball is delivered he gives an explosive grunt as he gets to the wicket.

“Some approach the crease very quietly, like Freddie Flintoff who hardly made a sound, whereas Shane Warne, as a leg-spinner, had a huge grunt.”

Du Plessis can also determine which batter is on strike through the sound of their voice, and the direction in which the ball is hit by the noise it makes off the bat.

“In terms of batting you just listen very carefully to how the batters communicate with each other,” he says.

“When Andrew Strauss and Marcus Trescothick used to bat together, Trescothick would always just say “run” when he hit the ball whereas Strauss would say “Yeah come on, come on, come on”.

“And when the ball is hit through the off side, it has a very sharp, crack sound, as opposed to the ball being played through the leg side.

“I can also tell when sweep shots are being played because you can hear the bat hitting the ground with a scraping sound.”

‘I think I have found my niche’

A lifetime of listening to cricket coupled with the ability to recognise people by sound, touch and smell has enabled to Du Plessis to forge a successful career as a broadcaster.

A presenter of his own cricket podcast, he says his commentary work may need to take a back seat due to health reasons.

“I think I will have to do less of the commentary and that’s mainly due to the fact that I’ve lost quite a bit of my hearing, especially in my left ear,” he explains.

“Apparently that’s a common thing with blind people because we use our ears so enthusiastically.

“But I think I have found my niche in hosting, presenting and doing podcasts. I would love to progress my broadcasting career and perhaps emigrate from Zimbabwe, ideally to a cricket-playing nation.”