Miniso is the purveyor of inexpensive but sleekly designed household goods, such as $2 mascara and $6 headphones.

Courtesy of Miniso

In the pre-Covid era, Ye Guofu, the founder of Chinese affordable lifestyle retailer Miniso, would spend months overseas scouting out potential new markets. While the pandemic has temporarily paused his trips abroad, it hasn’t thwarted his plans for international expansion. “Our company is still thinking of ways to grow,” the 44-year-old says in an in-person interview at the firm’s headquarters in Guangzhou, one of his first with a major international media outlet. “I am confident of Miniso’s long-term prospects.”

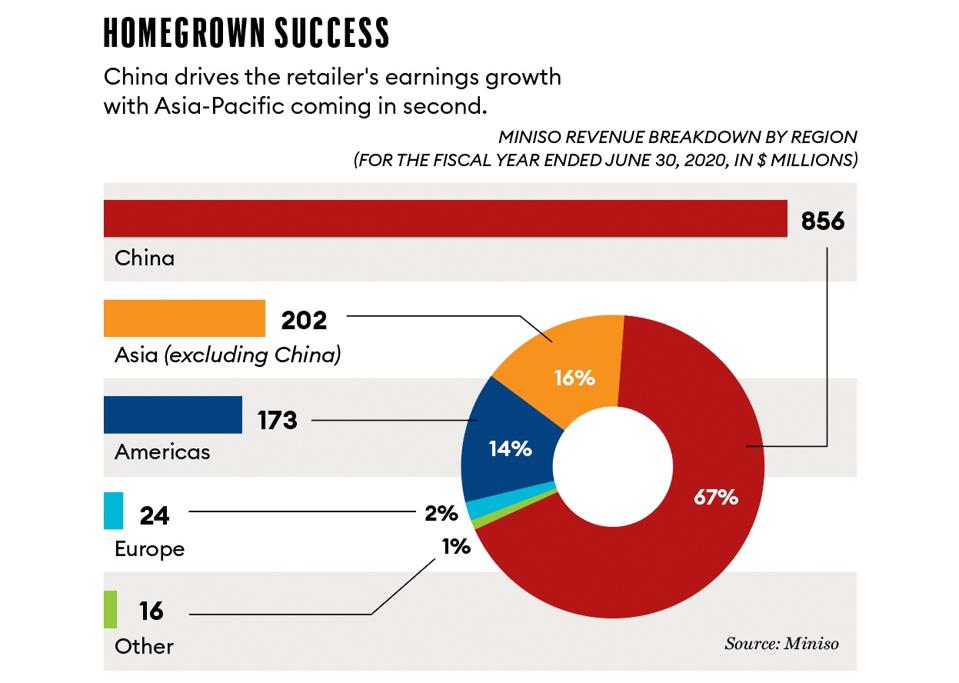

The buildout of Ye’s New York-listed chain continues apace. Despite the pandemic pummeling bricks-and-mortar retailers last year, the purveyor of inexpensive but sleekly designed household goods, such as $2 mascara and $6 headphones, opened more than 400 stores in the 12 months to September, including its first in Northern Europe. Of Miniso’s 4,330 outlets worldwide, about 60% are in China and the rest scattered across 80 countries and territories. All stores share the brand’s hallmark design of clean lines and neatly arrayed merchandise, with a striking similarity to Japanese retail titans Muji and Uniqlo.

Ye, whose $6.6 billion fortune is based on his Miniso stake, is preparing to open more stores abroad this year. While temporary store closures and reduced opening hours weighed on income last year—third-quarter sales fell by 30% year-on-year to $305 million—the entrepreneur is confident that demand for his low-cost products is resilient. Amid the global economic downturn, newly budget-conscious consumers are on the hunt for quality but affordable goods, while the vaccine rollout and easing stay-at-home restrictions will bring shoppers back to stores, he believes.

Ye says this has already happened in China, where both sales and foot traffic at Miniso stores have nearly recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Nationwide, retail sales grew 5% in the fourth quarter from a year ago, according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. For the next quarter, the firm is projecting revenues of around 2.3 billion yuan ($355 million).

For his fast growth in China, Ye Guofu earned the nickname kai dian kuang mo, or the store-opening maniac.

Courtesy of Miniso

He is similarly optimistic about international markets. With retail vacancies up and rents down, Ye says it’s a good time for the firm and its franchisees to secure new leases, with the opportunity to grow outweighing potential risks. His company has been working with its local partners to identify new locations and size up the pandemic’s impact on the appetite for its merchandise while navigating government restrictions. It’s the new normal for the firm. In December, Miniso opened its first store in Iceland after a six-month evaluation. “Iceland didn’t have a business like ours before,” says Ye, who adds he’s been satisfied with sales so far.

Jason Yu, a Shanghai-based managing director of consultancy Kantar Worldpanel, says Miniso has unique opportunities ahead. “Many companies have become risk-averse and wouldn’t dare to expand now,” he says. “It can be a good time to get prime commercial properties, and Miniso’s pricing strategy also makes it popular to consumers whose income has been affected.” Investors are optimistic, too. Miniso raised $608 million in a U.S. public offering in October, giving the company a current market value of about $10 billion.

Ye says he is particularly bullish on long-term growth in the U.S., India, Indonesia as well as in Latin America, where the firm already has a large customer base. “In the future, probably more than half of our stores will be located abroad,” he says, but declines to give an exact timeline. “Progress depends on the pandemic, but it won’t take us very long.”

Of its stores globally, Miniso only directly operates 120. Instead, the company employs what Ye calls an asset-light model, where its franchisees are responsible for leasing properties. This, he says, has allowed the company to expand quickly since its launch seven years ago. Miniso, for its part, trains staff, supervises sales strategies and provides the products. The partners’ cut is between 33% and 38% of revenues generated on a daily basis, according to Vincent Huang, vice president in charge of global operations.

To help its partners navigate challenges, Ye says Miniso is much more involved than other chain businesses, where, for example, a franchisee simply sources the goods and sells them under the owner’s brand. “Our franchisees prepare the money [to launch a store], but the right of management and operation still lies with us,” he explains. Partners typically recover initial costs such as personnel and real estate in about 12 to 15 months, according to company documents.

Miniso’s biggest near-term challenge remains the fallout from the pandemic, which could continue to hurt sales. But Ye sees a global recovery on the horizon, and he’s pushing ahead with expansion plans which include launching in Portugal in January. “I think I am aggressive,” says Ye. For his fast growth in China, Ye earned the nickname kai dian kuang mo, or the store-opening maniac. “But behind this aggressiveness is confidence in my business,” he says.

The youngest son of peasant farmers in landlocked Hubei Province, Ye grew up curious about the world beyond China. “My father used to buy calendars from the local farmer’s market, and I got to see photos of big cities like Beijing, Los Angeles and New York,” he says. “So I thought, ‘When I grew up, I would venture out of the mountains and check out what it’s like out there.’”

After graduating with an economic management degree from Zhongnan University of Economics and Law, Ye moved to the coastal province of Guangdong when he was 21 to find a job. After a three-month search, he was hired as a salesman at a local steel-pipe factory.

Ye later sold pottery with a friend, but they fell out over how to manage the fledgling business. He then tried selling cosmetics and accessories. This led him to start a discount store called Aiyaya, where everything was priced under 10 yuan. Ye reinvested his profits and grew the business. But then came a trend of “consumption upgrade,” he says, and the market for cheap, disposable goods began to shrink in favor of more quality products.

His inspiration for Miniso came during a 2013 trip to Japan, where he observed Muji and Uniqlo’s popularity with browsing shoppers: Their designs were attractive, and the goods affordable. “So I thought, ‘Why not bring the format back [to China]?’”

To imbue a feel of Japan into his own stores back home, Ye enlisted Japanese freelance product designer Miyake Junya, who has since become Miniso’s chief designer. With his help, Ye opened the first Miniso store in Guangzhou in late 2013. The Aiyaya stores were gradually shut down and Ye focused entirely on his new brand.

The aim from the start was to build a global business. “The standard of living in Guangzhou isn’t that different from Singapore or Malaysia,” he says. “I feel [that] if I can do it in Guangzhou, I also have a chance abroad.” In the following years, Miniso signed on franchisees to push the company’s reach, some of whom were introduced through trade organizations in Guangzhou. In 2014, Miniso launched stores in Japan, Singapore and Malaysia, and then expanded worldwide.

Of Miniso’s 4,330 outlets worldwide, about 60% are in China and the rest scattered across 80 countries and territories. All stores share the brand’s hallmark design of clean lines and neatly arrayed merchandise, with a striking similarity to Japanese retail titans Muji and Uniqlo.

Courtesy of Miniso

Pedro Yip, a Hong Kong-based partner at consultancy Oliver Wyman, says next up for Miniso is to localize its offerings. “They are still at the initial phase of globalization,” he says. “One future challenge is to tailor products for each market. For now, what they sell abroad isn’t that different from what they sell in China.”

The entrepreneur remains attentive to Miniso’s product designs; his team comes up with about 100 new products to sell every week, which he personally approves. He also has a hand in designing store merchandise, including the water bottle that sits on his office desk, which he says has thicker walls than other water bottles to keep water cooler.

He closely follows the latest buying trends, too. After the blind box toys craze hit China—collectable figurines that are sold in opaque packaging—Ye spent a year recruiting artists and preparing for his own toy store. In December, Miniso launched Toptoy, which sells collectible cartoon figurines in Guangzhou. It is the company’s first toy store, and Ye hopes to expand the concept overseas.

Ye calls the concept a “revolution of traditional toys.” He notes: “Both China and abroad are seeing explosive growth of new forms of consumption, and we are actively preparing for it.” The company will also continue to expand its online presence both at home and abroad. In China, it has stores on Alibaba’s Tmall site, while globally it sells its merchandise through Amazon, Lazada and Shopee. The pandemic is speeding up its shift to digital sales, which contributed 5% of sales in the third quarter, up from less than 2% a year earlier.

Wu Jincao, an analyst at Suzhou-based Soochow Securities, says the company may face increasing competition from the likes of Walmart and Uniqlo globally, because they also target frugal shoppers looking for value. Ye brushes the competition aside. “I don’t see any obvious competitor for now,” he says. “We are smaller than Walmart and we target younger consumers. We are really a new type of business.”

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/603ca5ce10f839adc27f0428/0x0.jpg)