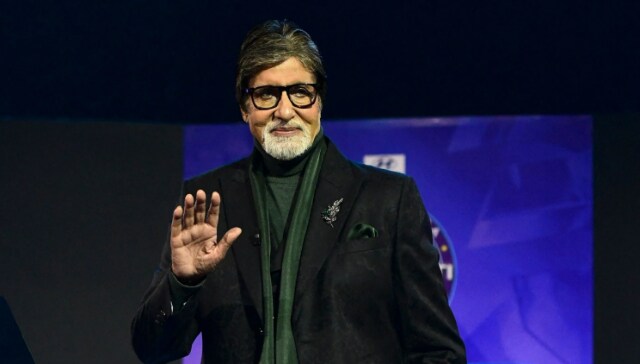

Amitabh Bachchan is no more an actor. He is a metaphor for performing skills. It’s like Varun Dhawan telling Varun Dhawan, ‘Tu apne aapko Amitabh Bachchan samjhta hai kya?’ Or when your Dad pulls out his best angry shot at you and you say, ‘Dad, don’t do a Bachchan on me’. Or when you are pulled up for breaking a queue and you quip, ‘Main jahan pe khada hota hoon line wahin se shuroo hoti hai.’

Choosing his best is not about zeroing on his most obvious hits, as PVR’s Bachchan Back To Beginning festival to commemorate his 80th birthday on October 11 has done. The selected films are Don, Chupke Chupke, Satte Pe Satta, Amar Akbar Anthony, Deewaar, Mili, Namak Halal, Kaala Patthar, Abhimaan, Kaalia, and Kabhi Kabhie.

That’s it. Why are Chupke Chupke, Kaalia and Kala Patthar even in the list? Two of these are not even good films, and they certainly don’t feature AB at his simmering best. As for Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Chupke Chupke, the film belonged to Dharmendra, Sharmila Tagore and Om Prakash. Mukherjee himself told me that Amitabh Bachchan and Jaya Bhaduri agreed to do small parts out of their love and respect for their ‘Hrishi Kaku’.

Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s vintage Bachchan vehicles were Abhimaan, Mili (both included in the PVR packaged), Anand, Namak Haraam (not Namal Halaal, which is a three-hour nautanki-showreel for the super-performer) and most importantly Bemisal.

I consider Hrishikesh Mukherjee’s Bemisal to be Mr Bachchan’s best performance to date. Released in 1982, and based on a Samresh Basu novel Bemisal is the story of curiously cynical do-gooder. Bachchan plays Sudhir, a delinquent orphan taken in by a kind government officer (Om Shivpuri) who brings up Sudhir and his own biological son Prashant (Vinod Mehra) as equals. Later, much later, on his deathbed after a sudden heart attack, he tells his Bahu Kavita (Raakhee), “My son is weak. But whenever you’re in a crisis you can blindly depend on Sudhir.”

Prophetic words, those. As the exceptionally eventful plot moves forward we see how slyly and noiselessly Sudhir keeps stepping in to bail out his benefactor’s son. But here’s what makes Bemisal a unique and refreshing tale of sacrifice and self-annihilation. The sacrifices made by Sudhir are never apparent until much later when the passage of time shows the true enormity of how much Sudhir gives away to the friend whose father gave him back a childhood that would have otherwise been squandered on the streets.

There is a message on adoption in Bemisal. Om Shivpuri says, “I was advised, ‘Get a dog. Never bring a street-child home.’ I didn’t listen to anyone. It was the best decision of my life.”As played by Bachchan Sudhir emerges as a smirking enigma. Not just misunderstood by those who love him, but he also quite enjoys being perceived as being quite the opposite of what he really is. The role of the closet martyr is done by Bachchan with exceeding intelligence and sensitivity. We are never allowed to feel sorry for this noble sacrificing soul. Bachchan never glorifies his character’s generosity of spirit. He bleeds internally. He cries silent tears. He gives and he gives. Because that’s the only way he lives.

Most unique is the relationship that forms between Sudhir and his friend Prashant’s wife Kavita played by Raakhee Gulzar. He calls her ‘Sakhi’ throughout the film and flirts outrageously with her in front of her husband and even her father-in-law. He tells her his deepest secrets including those about his secret flings.Finally, when he goes to jail and, in the film’s most memorable sequence, she comes to visit him in his favourite white saree with a red border, Sudhir lets Kavita, and us, have a peep into that fortified heart of his.

And how could any Bachchan festival be complete without Shakti (1982)? Although Sholay continues to be Ramesh Sippy’s signature work it is to many of his admirers an inferior work to Shakti which he made seven years after Sholay became a landmark and benchmark for successive generations of Indian filmmakers. But sorry, Shakti, it is that does it for me. And it’s not just about the historic union of the mighty Dilip Kumar with his greatest successor Amitabh Bachchan. It’s a lot more.

The sheer velocity of the screenplay, the structuring of the father-son conflict, the deeply contoured sketching and execution of the characters as they hurl towards an amazing nemesis, simply make Shakti the most powerful script that the awesome twosome Salim-Javed ever wrote. This is a far superior screenplay to the duo’s other celebrated Bachchan films including Zanjeer and Deewaar. This was one of Dilip Kumar’s last really great performances. Like the rest of the humanity from the entertainment industry, the Big B and director Ramesh Sippy were in awe of the mighty Dilip Kumar. But they never allowed their reverence to come in the way of keeping the plot and characterizations balanced. The father-son conflict never gets tilted.

And Saudagar(1973)! This is the most morally bankrupt character Mr B has ever played. Moti is a man so lowdown and dirty he marries a graceful widow (the mythic Nutan) uses her for business purposes and then dumps her to marry his shallow sexed-up sweetheart (Padma Khanna). Playing a toddy extractor, the Big B actually got into a dhoti and climbed the palm tree. I’ve never seen his transformation into a character being so complete in any other film. Directed by Sudhendu Roy, Saudagar deserves to be rediscovered. It is a certifiable classic.

Finally the last great performance from Mr Bachchan in Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black. It’s impossible to imagine any actor playing Debraj, the tutor of manic proportions raging into the darkness like a Shakespearean tragic hero.To say this was Bachchan’s finest in years ever isn’t enough. For, what he has done with his character in Black is to endow Indian cinema with a flavour of flamboyant excellence, unparalleled by anything we’ve seen any actor from any part of the world do or say…I say ‘say’ because the way Bachchan has used that well-known baritone has to be heard to be believed. Dropping his voice to a whisper he raises it again to challenge destiny, and toast immortality.

Black unleashes a fury of never-felt emotions. Master-creator that he is, Bhansali peels away layers and layers of passion and pain in Debraj’s character. We can’t turn away. Bhansali doesn’t give us that choice. It takes a while to come to terms with the awesome and overpowering emotions of Bhansali’s world. What is this twilight zone of resplendent suffering where every hurt is felt like a whiplash? Indeed the quality of cinematography by Ravi Chandran and the background music by Monty is so steeped in the ethos of anxious yearnings, we feel the characters’ hearts are forever on the verge of bursting open. As Debraj makes Michelle ‘see’ into the light through her blindness, he goes blind and finally loses his mind. In the best most heart-wrenching moments of the film, Michelle rattles the chains that are put on her guru to prevent him from causing himself bodily harm.

That frenzied chain rattling becomes symbolic of everything that Bhansali’s incredibly grand cinema attempts to do. The darkest most inexpressible thoughts acquire shape in Bhansali’s tortured and yet incredibly beautiful realm of self-expression.

It is time for Mr Bachchan to break those chains and work again with a director like Bhansali who is not just a fanboy but also a genius of a storyteller and knows how to harness that part of the Bachchan persona that is yet to emerge.

Oh yes, there is more in there.

Subhash K Jha is a Patna-based film critic who has been writing about Bollywood for long enough to know the industry inside out. He tweets at @SubhashK_Jha.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.