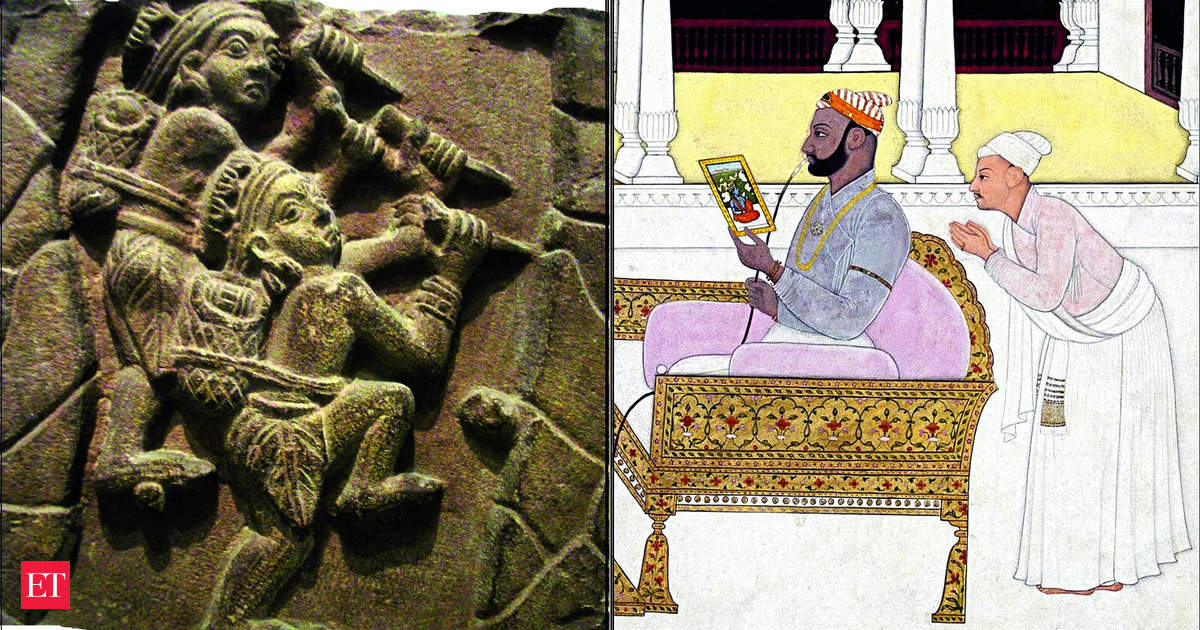

A rocky terrain surrounds them. They appear to be chiselling or excavating a rock-cut cave along a steep cliff-side. Although the identity of these two men, as intended over two millennia ago, remains open to interpretation, it does look as though this exquisite sculpture from 2nd century BCE Bharhut Stupa in Central India images ancient Indian stone-workers. In which case, what we have here is an extremely rare – the very first – self-referential sculpture of ancient Indian artisans at work.

For all our collective national pride in the greatness of Indian art, especially that belonging to a remote and ‘glorious’ past, there has been very little curiosity about its makers. How did ancient and medieval Indian architects, sculptors and painters register their presence? How did they perceive themselves and their contributions as artists? What clues have they left behind to help us in catching a glimpse of their working methods and aspirations? Surprisingly, such questions were sidelined even in Indian art historical scholarship until about five decades ago.

Before the 1970s, the ancient Indian artist was believed to be an anonymous figure – one who did not seek recognition, and who created art that was infused with an ‘other-worldliness’, a quality that transcended the physical sensuality that gives art its very form. From the early 1970s, social histories of art began to gain ground. It was also a time of great ferment in writing about art and its makers.

Among those who played their part in drawing attention to the makers of art, one cannot but recall three grand masters of Indian art history. Contemporaries and friends, each of them had begun working independently, teasing out many hidden details about Indian artists.

Their work challenged the presumed anonymity of artists, interpreted their stylistic affiliations, their association with patrons, and their self-image as artists. Ram Nath Misra, with his formidable grasp of a range of texts on art and craft practices, opened vast resources to help understand the processes of art-making, the role of the artist, their hierarchies, and organisations into clans, families or gharana-traditions in large parts of northern and central India. Shadakshari Settar’s deep excavations of the inscriptions from Karnataka revealed for us not only the earliest available signature of an artisan-scribe named Chapada in Indian history (c. 3rd century BCE), but also much more about the names, signatures and mobility of southern Indian artists. And the impeccable aesthetic sensibilities and poetic vision of BN Goswamy – who passed away just last month — were matched only by his depth of insight and rigours of research that traced families of painters and their patrons as the basis of artistic style. These painters travelled in the hilly tracts and spread their oeuvre in the creation of Pahari miniature paintings.

The artistic vision and stylistic nuances of Nainsukh, an 18th century artist from Guler, whose self-referential portrait we see to the right of our composite image (photo), became known to us in modernity through Goswamy’s art historical labours. As Goswamy explains, it is the only work in which the painter Nainsukh and his patron Balwant Singh are seen examining a painting together: ‘When he paints his own likeness, he does so with no slurring over of a feature… Things are said with moving honesty.’

Sadly, the past four years have seen us lose all the three pioneering art historians who walked the trail of our master artists of yore. But not before they opened up new ways of seeing Indian art through the eyes of its artists.