“Hey mommy, when are we going to go after this seat?” she asked Mace, who had just won reelection to the state House.

The only non-incumbent woman elected to the Senate is a Republican: former Rep. Cynthia Lummis of Wyoming.

But the majority of the 24 non-incumbent women joining Congress in January are White, including 13 Republicans and five Democrats. At least 91 White women will serve in the 117th Congress, up from 79 this year.

The success of GOP women in the House

That means the number of Republican women in the House will at least double. (Currently there are only 13 women in the House GOP conference, and two of them did not run for reelection.) Democrats are adding nine new women, which balances out those they lost to defeat and retirement, increasing their numbers to 89 for now.

“Republican women are still going to be extremely underrepresented,” said Kelly Dittmar, director of research at the Center for American Women and Politics. “This year they were really making up for losses,” she added, noting that this time two years ago, there were 23 GOP women.

Whereas Democratic women have long been boosted by the pro-abortion rights group EMILY’s List, which stands for “Early Money is Like Yeast,” Republicans have lacked comparable infrastructure to invest in female candidates. There’s also been an ideological opposition to playing in primaries, especially in any way that would invoke identity politics.

“Women around the country have watched other women before them be successful and realize, ‘Hey, I can do it,'” said Iowa GOP Rep.-elect Ashley Hinson, who last week defeated Democratic Rep. Abby Finkenauer, one of the women who flipped a district in 2018.

“It was the perfect storm. We had competitive seats that were winnable and we had incredible women in those districts with prior legislative experience and who knew how to put a campaign together,” said Julie Conway, the executive director of VIEW (or Value in Electing Women) PAC, which has helped elect GOP women to Congress since 1997.

Just as Democratic women were in 2018, Republican women this year were well-positioned to take advantage of a favorable environment. “The only way that could have happened was if it was a better-than-expected year for Republicans, right, and I think it was,” Dittmar said of the gains GOP women were able to make.

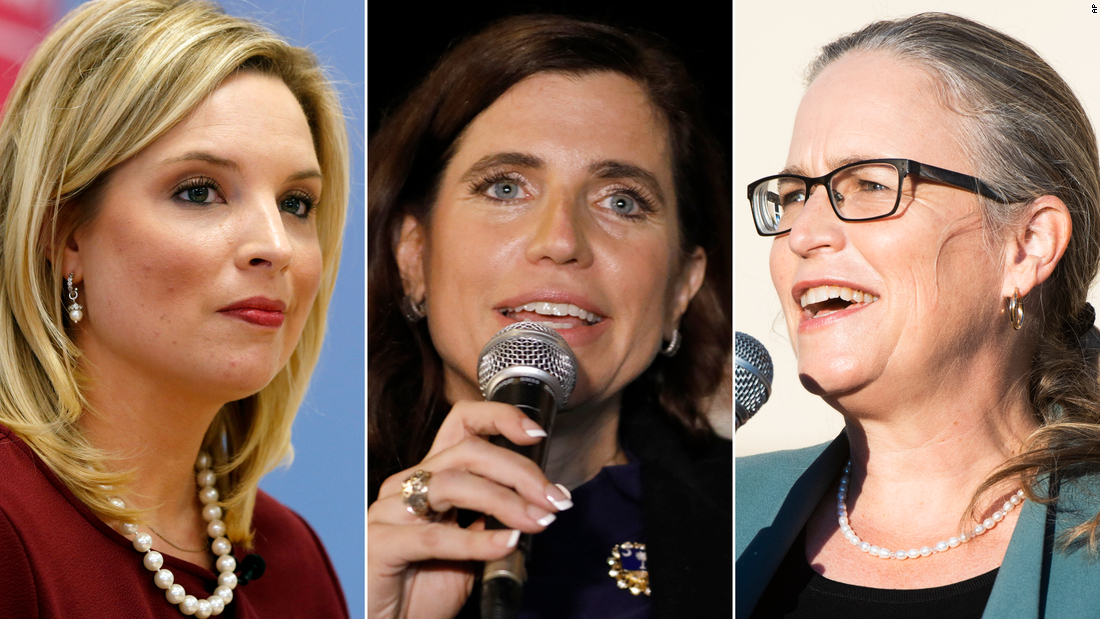

“Being the first Republican woman elected to Congress in the state of South Carolina is deeply humbling,” Mace said. “It reminds me that Democratic women do not hold a monopoly on breaking glass ceilings.”

New voices in Congress

Even with women in Congress breaking records, they will likely represent just over a quarter of the legislative branch. Obstacles remain — both to women running and winning.

Women candidates often receive questions their male colleagues do not — like who’s going to take care of their kids. For Hinson, out door knocking in her Iowa district, that was a moment to reflect on why she was running in the first place. “The lady at the door, she thought I should be at home with my children. And I basically said, ‘Well, I’m setting a good example for them.'”

The elected women agree the perspectives they bring to Congress are wanted — and needed.

“They picked me this time, they know that I’m a mom, I drive a minivan, you know, we have a regular life here in Iowa,” said Hinson, a state representative and former journalist who thinks her communication skills will help her in Congress.

A professor and former budget director for the Georgia state Senate, Bourdeaux first ran two years ago, coming up 433 votes short in a recount against the GOP incumbent who decided not to run again in 2020. “Many people here didn’t even know that there were Democrats in their neighborhood,” she said of the groundwork that that initial race laid.

“A lot of women were very much galvanized by Donald Trump, and their concerns over the direction of the country, and the loss of really basic rights — reproductive rights — that all of a sudden was on the ballot in a way that it was not before. So being a woman, I think, was helpful in speaking to those issues,” Bourdeaux said.

Mace, the South Carolina Republican, finds herself at the opposite end of the political spectrum, but she too feels strongly about bringing her perspective to the House.

“Freshman year at the Citadel was a lot like running for Congress,” she said, noting the challenges and the significance of both achievements — and the way gender impacted her experience.

“I mean, you can be tough, but you can’t be a B-I-T-C-H, right? There’s a boundary there as a female candidate that you can only be so tough before you cross that line and people start judging you in a different way.”

“The ability to stand up against members of your own party, even when it’s leadership, especially now more than ever is more important to voters,” Mace said.

Looking ahead

Many of the Republican women who won this year were in competitive districts. Republicans have flipped eight Democrat-held seats, according to CNN projections so far, and women have delivered all but one of those wins. That means they’re likely to face difficult reelections in the future, possibly against Democratic women.

That worries Conway of VIEW PAC, who fears that Democratic and Republican women will continue knocking each other out in the most competitive seats every two years. “The whole idea of having ‘girl seats’ does not get us any closer to parity,” she said.

A record 643 women ran for Congress in 2020 — 583 for the House and 60 for the Senate. That’s double the number of women who ran in 2016, though it has not yet translated to twice as many seats.

That is in part because as more women run for office, they are also more often running against each other, both in primaries and general elections. In 2016, women ran against each other in 17 House and Senate general election races, according to data from the Center for American Women and Politics. In 2020, that grew to 51 races with women challenging each other.

The answer? Encouraging even more women to run.

But helping each other may not always come naturally, some said. “Women are far worse on other women than they are on their male colleagues,” said Mace, reflecting on her experience at the Citadel, in business and in politics. “Women don’t like to see other women be successful.”

“I do feel like it’s gotten better over the years, but I see it more often than not, and it’s true on both sides of the aisle. That’s why I’m always encouraging women to run.”