It is now a common observation that the old-school definitions of identities are ceasing to exist in the rapidly paced modern world. The rise of big corporations, concrete jungles, and few elite people not looking for caste, religion, or ethnicity for marital relations are cited as examples.

Most of us would wish the world to be as simple as this.

However, the other side of the coin is that the intensity of debates, discussions, and violence has increased in recent years. One incident, and the other side retaliates with absolute inhuman vengeance, as seen recently in Bahraich.

Sociologists, especially UPSC teachers, might want to ignore these as aberrations, but the consolidation of localised identities—such as those based on caste, linguistic, cultural, regional, and, of course, religious lines—is taking place at an unprecedented pace. We now have WhatsApp groups related to different communities.

Admins in these groups break down complex government decisions or policies and decode whether they will suit that identity or not. If yes, all is well and good. If not, then a course of action, which is majorly disruptive in nature, is taken.

India first saw glimpses of this in the protests against the Supreme Court amending the SC/ST Act. The government bent down and did what these groups demanded. Then came the CAA/NRC-related protests, which went as far as threatening India’s sovereignty.

Similarly, states like Bihar, Maharashtra, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, among others, have been pitching for their own economic and social benefits. States, districts, or particular regions within states taking such activism on their own part broadly come under the category of sub-nationalism.

While these are examples of decentralised democracy, what has changed for the average man? For him, the larger question is whether his community will support him or not when he is targeted because of his own identity. That is the ultimate test of such identities we see in this modern, rational world.

One way to guess the answer is to examine whether those consolidated identities work in the same way as they used to in the past.

To put it simply, if a Bangladeshi asserting his claim on Bengali identity attacks a Bihari, will Biharis run to save him because he is a Bihari? Or, if an ethnic Bengali attacks another Bengali due to religious bigotry, what will the person under attack do? Call his co-religionists or others who also share the Bengali identity?

Let us look at a few recent conflicts on these parameters.

In the Arab world, Israel is fighting with Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Houthis. It is, in essence, an ethnic as well as a religious conflict. However, ethnicity is not being considered much here as a sign of loyalty; religion is.

On the other hand, in Iran’s rivalry with Saudi Arabia and other Arabs, the sectarian conflict in the form of Shia vs Sunni is dominant. One might assume that despite sectarian conflict, the Arab world may side with Iran in exigency due to the same religion. But it is divided here too.

Countries like the UAE and Saudi Arabia may be willing to sacrifice Iran in lieu of economic interests, while Qatar would hesitate to do so. Many believe that Iran’s Persian ethnicity does not let Arabs treat them on the same page.

The mixed nature of these conflicts, at the place where Islam originated, should have meant that those who converted later would take their non-religious identities more seriously. It actually makes more sense for them since, lacking a first-mover advantage, it is much better to find local partners.

That is what secularism has been used for in the Indian subcontinent. The ideal goal written down in the Preamble by Indira Gandhi has been used as a tool for assimilating minority (Muslims mainly) identity into ethnic and sub-nationalistic patterns. At the same time, minority communities are also accorded the privilege to maintain their own religious affiliations, guarded by their own rules and regulations—sometimes going to the extent of not following constitutional guardrails as well.

Seven and a half decades of this experience tell us that wherever minorities are less than 20 per cent, they overtly identify themselves as Bihari, Jharkhandi, Bengali, Tamilian, Dravida, Kannadiga, Marathi, Gujarati, UPite, Malyalis among others. In that way, they tend to develop rapport with the local population (mainly Hindus) and co-exist until they become the majority.

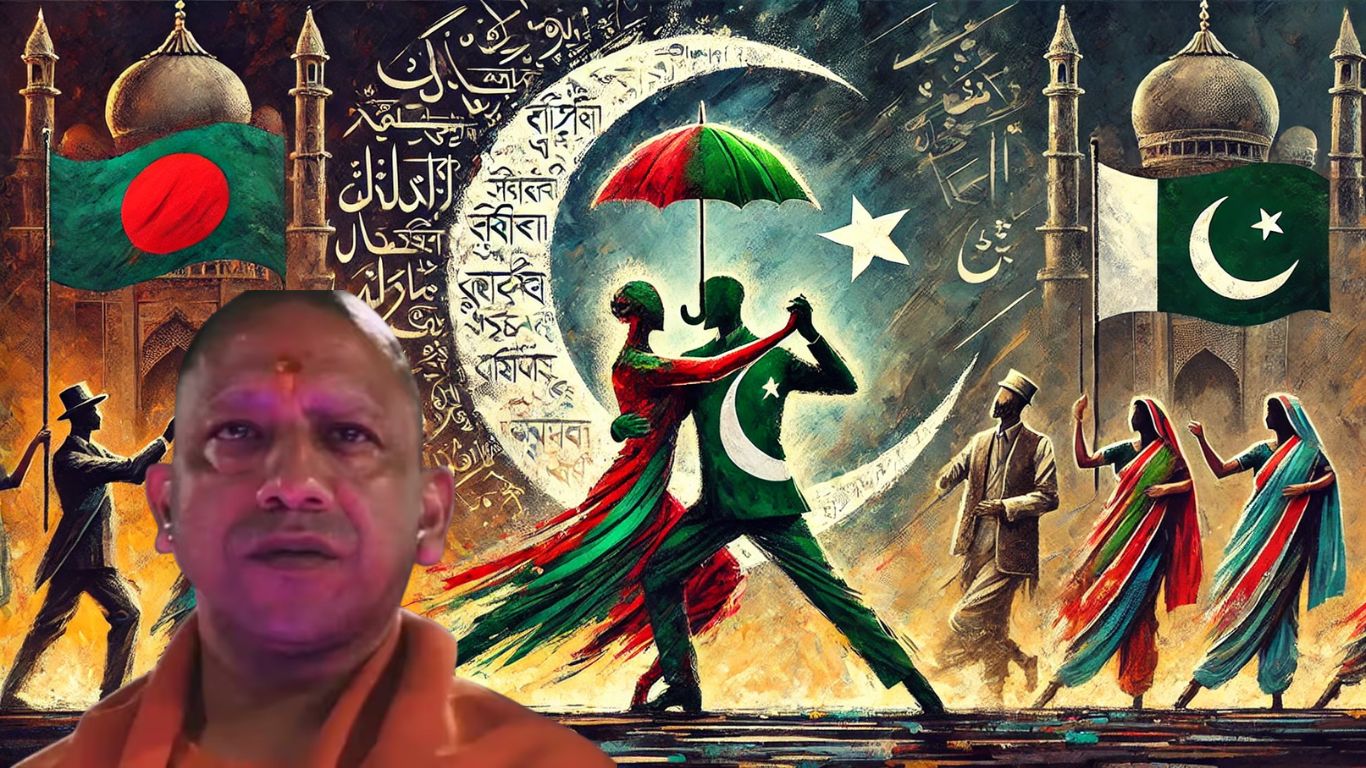

Sure, language may well be the umbilical cord that connects people, culture perhaps another but, whether you like it or not, ultimately it boils down to religion – example being Bangladesh where, common language, culture, icons have not managed to save the Hindus: @jsaideepak pic.twitter.com/2aMAV8um1N

— Anand Ranganathan (@ARanganathan72) December 13, 2024

At the same time, they also run their own society with personal laws. Contrarily, Hindus who have coexisted with them for a long time tend to secularise their traditions, morals, and laws. These include people from Moradabad, Kashmir, West Bengal, and also Bangladesh.

The consequences, however, have not been positive for them. In Kerala, the Malyali identity has not proven to be an effective binding force, and the state became notorious for sending the most recruits to the dreaded ISIS.

Similarly, in Karnataka, language-based galvanisation could not supersede religious affiliations, and until a few years ago, the state topped South India in communal violence.

Even at the peak of the coronavirus pandemic, NCRB data says that the number of religious riots increased by 100 per cent in 2020. At all these places, state-sponsored assimilation had been going on for decades, but nothing worked.

However, the ultimate eye-opener for any youth who did not witness the genocidal campaign against Kashmiri Pandits (where Kashmiriyat failed and religious persecution won) is the ongoing anti-Hindu pogrom in Bangladesh. Until a few months ago, Sheikh Hasina had kept the whole of Bangladesh united under the flag of Bengali identity.

The mirage collapsed quickly, and the whole world is witness to what Bengali Muslims are doing to Bengali Hindus, whom they must have referred to as brothers during good days.

Rationalists and seculars believe that the onset of rational thinking will erode religious identities and replace them with something smaller and better. Global patterns show that rationalism is used as a shield by perpetrators of religious persecution.

Indians would like to forget the tiny segments of their fragmented identities — ethnicity, regional, culture or linguistic – and unify under one big religious belt, or else our disturbed neighbourhood awaits us.