Getty Images

Getty ImagesResearchers have made a scientific discovery that in time could be used to slow the signs of ageing.

A team has discovered how the human body creates skin from a stem cell, and even reproduced small amounts of skin in a lab.

The research is part of a study to understand how every part of the human body is created, one cell at a time.

As well as combatting ageing, the findings could also be used to produce artificial skin for transplantation and prevent scarring.

The Human Cell Atlas project is one of the most ambitious research programmes in biology. It is international but centred at the Wellcome Sanger Institute in Cambridge.

One of the project’s leaders, Prof Muzlifah Haniffa, said it would help scientists treat diseases more effectively, but also find new ways of keeping us healthier for longer, and perhaps even keep us younger-looking.

“If we can manipulate the skin and prevent ageing we will have fewer wrinkles,” said Prof Haniffa of the Wellcome Sanger Institute.

“If we can understand how cells change from their initial development to ageing in adulthood you can then try and say, ‘How do I rejuvenate organs, make the heart younger, how do I make the skin younger?’”

That vision is some way off but researchers are making progress, most recently in their understanding of how skin cells develop in the foetus during the early development stage of human life.

When an egg is first fertilised human cells are all the same. But after three weeks, specific genes inside these so-called “stem cells” switch on, passing along instructions on how to specialise and clump together to form the various bits of the body.

Researchers have identified which genes are turned on at what times and in which locations to form the body’s largest organ, skin.

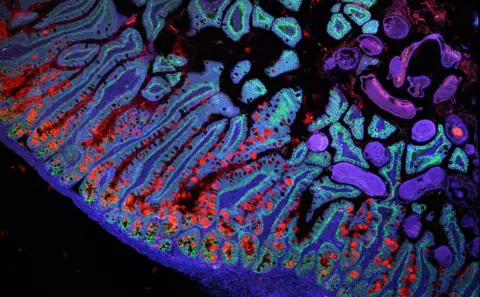

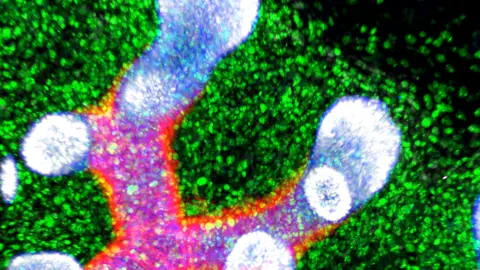

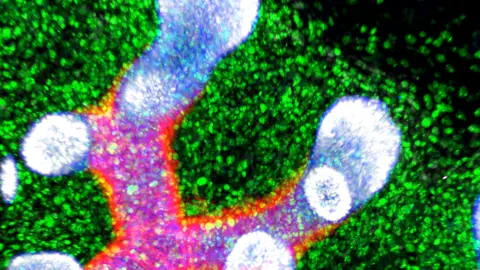

Under the microscope and treated with chemicals they look like tiny fairy lights.

Genes that turn orange form the skin’s surface. Others in yellow determine its colour and there are many others which form the other structures that grow hair, enable us to sweat and protect us from the outside world.

The researchers have essentially obtained the instruction set to create human skin and published them in the journal Nature. Being able to read these instructions opens up exciting possibilities.

Scientists already know, for example, that foetal skin heals with no scarring.

The new instruction set contains details of how this happens, and one research area could be to see if this could be replicated in adult skin, possibly for use in surgical procedures.

In one major development, scientists discovered that immune cells played a critical role in the formation of blood vessels in the skin, and then were able to mimic the relevant instructions in a lab.

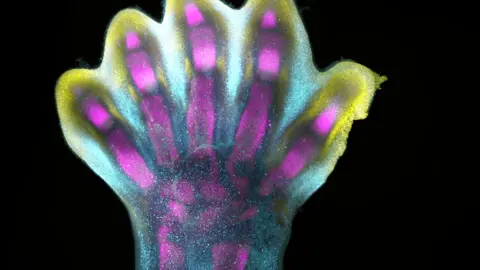

They used chemicals to turn genes on and off at the right time and in the right places to grow skin artificially from stem cells.

So far, they have grown tiny blobs of skin, out of which have sprouted little hairs.

According to Prof Haniffa, the eventual aim is to perfect the technique.

“If you know how to build human skin, we can use that for burns patients and that can be a way of transplanting tissue,” she said.

“Another example is that if you can build hair follicles, we can actually create hair growth for bald people.”

The skin in the dish can also be used to understand how inherited skin diseases develop and test out potential new treatments.

Instructions for turning genes on and off are sent all across the developing embryo and continue after birth into adulthood to develop all our different organs and tissues.

The Human Cell Atlas project has analysed 100 million cells from different parts of the body in the eight years it has been in operation. It has produced draft atlases of the brain and lung and researchers are working on the kidney, liver and heart.

The next phase is to put the individual atlases together, according to Prof Sarah Teichmann of Cambridge University, who is one of the scientists who founded and leads the Human Cell Atlas Consortium.

“It is incredibly exciting because it is giving us new insights into physiology, anatomy, a new understanding of humans,” she told BBC news.

“It will lead to a rewriting of the textbooks in terms of ourselves and our tissues and organs and how they function.”

Genetic instructions for how other parts of the body grow will be published in the coming weeks and months – until eventually we have a more complete picture of how humans are built.