In a scene from Raj Khosla’s Ek Musafir Ek Hasina (1962), Ajay played by the charming Joy Mukherjee sings the soulful “Bohat Shukriya…” on the harmonium. Ajay has lost his memory after being hit on the head by Kabaali invaders in the Kashmir region of 1947, but he can somehow instantly play the Harmonium if it is dropped in his lap. Holed up in a shanty somewhere in the hills alongside Asha (Sadhana)- a runaway bride who has just escaped a toxic marriage – Joy saunters through a story where he falls in love, before being resurrected in a previous life. Hindi cinema has often used Amnesia as a trope to affirm its ideas of fullness. Where while love is the source of life, memory must be the genesis of meaning. It’s why we yearn, exact revenge and find in our past reasons to long for a future. The present, you could argue is just a tool.

In Asit Sen’s Khamoshi (1969), Radha played by a haunting Waheeda Rehman brings an amnesiac Dev (a small cameo for Dharmendra) back to his senses and falls in love with him in the process. Radha’s care is declared an instinctive cure and the subject of research at a hospital where mental patients come and go. Its view of mental health withstanding, Khamoshi is a stunningly poignant film anchored by the incredibly restrained performance of Rehman. Here memory isn’t just a trope that helps the narrative yield to twists and knots but is the burden that the protagonist must bear as the noise – as opposed to the silence – that only she can hear. It’s a terribly affecting performance, and a film that though hammy in its use of medical jargon, uses memory as both the fabric and the knife. We are what we are how we remember each other, the film says.

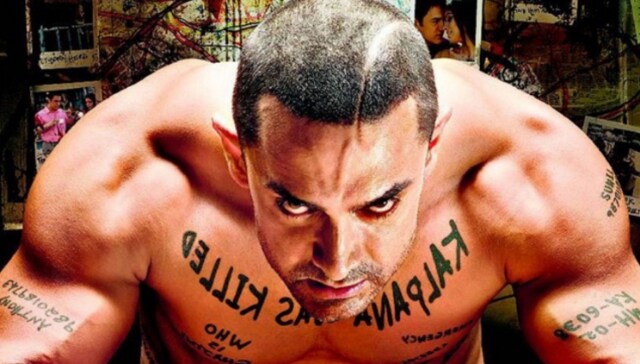

Memory is a conduit for life. It’s how we remember people, that we in response treat them, pursue friendships, relationships and construct plans, however, elaborate, with them as a part. Memory is what gives life structure, any sense of meaning really because come to think of it, our senses are calibrated to only interpret the present. At least in its material form. But it is really memory that tells us who we are and what people are to us in the context of our being. The trope of losing your memory has since the heyday of its discovery been applied with regular use. In Andaz Apna Apna, for example a protagonist pretends to have lost his memory to get close to a love interest. In Aamir Khan’s Ghajini, memory is essentially the cause of entropy, a restlessness born out of the desperation to make sense of things. In Sanjay Leela Bhansali’s Black, it is employed as the chink in the armour of a symmetric, coming-of-age story. In Henna (1991) amnesia sets you free, opens you up to the possibilities of other cultures and politics.

Mark Twain once wrote that “A clear conscience is the sure sign of a bad memory.” It’s the past that generates guilt, relief, a sense of rootedness, a vague idea of the self and perhaps is our only way to self-identify in a world that is casually graduating towards a fluid sense of morality. Memory becomes History when threaded through the needle of academic rigour and politically committed to the significance of our present day lives. From nationalities to ritualistic heritage, without being attested by heritage of some sort, you could argue, we’d all be refugees of a life without a story.

Everything we believe, question and imagine is a function of how we remember. But memory, as Khamoshi’s sobering portrayal of transactional love illustrates, gives meaning to our emotion. Our pain might only be pain if someone remembers causing it. Our love might only be love if someone has the memory of having felt it, even in moments when they cannot. Tragically, we are all amnesiacs to an extent, for life’s chaos blurs whatever maps we have created for the convenience of finding the familiar. We often forget out of convenience rather than the malignant intention to erase. And while the two are dissimilar they have equally treacherous outcomes.

Not all tropes are massacred equally and the loss of memory, or amnesia as it is medically termed, has luckily survived the Bollywood writer’s penchant for treating pivots as arm-length sidebars to hang their stories on. In fact, bar a few exceptions, amnesia manifests in our stories to surreal effect, communicating both the tragedy of erasure and the validation of remembrance. We are, as long as we are remembered. It’s how we pursue life, not as a city to travel through but as a town that reflects on its inward looking windows an image of how you looked in the past. It’s what gives everything, even the things we don’t do, meaning. It’s why, in most of our stories, the memory eventually returns. For a boat at sea, forgotten by those onshore, has sunk already.

Manik Sharma writes on art and culture, cinema, books, and everything in between.

Read all the Latest News, Trending News, Cricket News, Bollywood News, India News and Entertainment News here. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.