The lure of lithium, the metal dubbed white petroleum, has proved irresistible for Gina Rinehart, Australia’s richest person and one of the world’s richest women.

But her entry into one of the commodities being driven higher by strong demand for the batteries used to power electric vehicles (EVs) is far from conventional.

While there are plenty of opportunities closer to her home town of Perth on Australia’s west coast, Rinehart has bought into a German lithium project that has already attracted her son, John Hancock.

Gina Rinehart at Roy Hill’s berths in Port Hedland.

Courtesy of Hancock Prospecting

The presence of mother and son on the share register of Australian listed Vulcan Energy is unusual as the two have had a difficult relationship thanks to a dispute over the terms of a family trust which became a factor in John changing his surname to that of his grandfather, the late Lang Hancock.

Rinehart’s fortune, estimated by Forbes at $17.2 billion, is based on the mining of iron ore in Western Australia.

The size of her stake in Vulcan has not been revealed but her master company, Hancock Prospecting, is listed as a cornerstone investor in a $92 million ($A120 million) capital raising completed last week. John Hancock revealed his 5.23% holding in Vulcan last month.

“Zero Carbon Lithium”

The appeal of Vulcan, which lists Goldman Sachs has one of its high-powered advisers, is that the lithium it proposes to produce at site near Mannheim in the Rhine Valley will be marketed as the world’s first “zero carbon lithium.”

The claim of being extremely environmentally friendly is based on the production process, which will involve extracting very hot, lithium-rich brine that will be both the source of the lithium and the steam to drive electricity producing turbines to power the operation.

The first stage of the process will use proven geothermal technology to tap into the deep brine. The second stage will see lithium extracted with the used brine re-injected ensuring no wasted water. The final stage will see the production of lithium hydroxide, the chemistry preferred by battery makers.

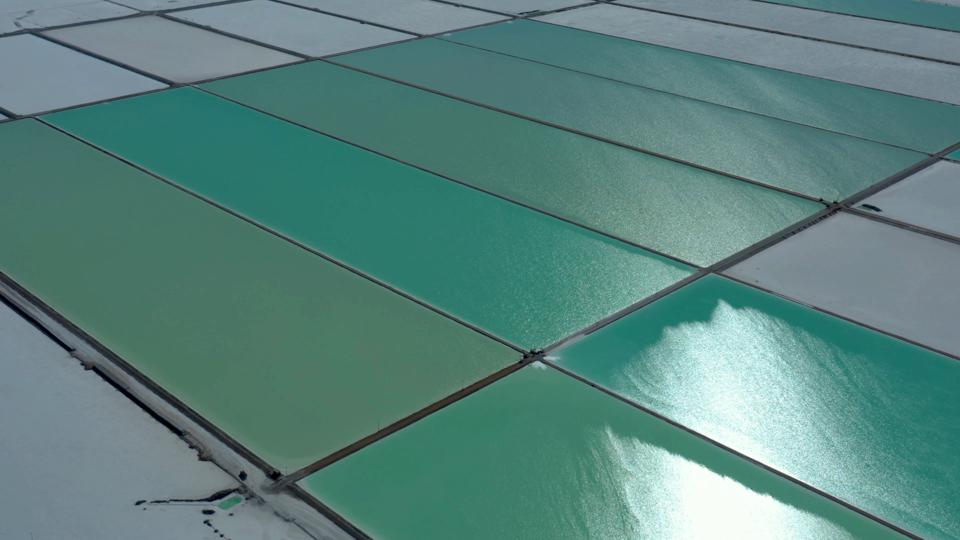

Lithium production in Bolivia, using the sun to evaporate surplus water. Photographer: Pablo … [+]

AFP via Getty Images

Vulcan’s proposed lithium production method is radically different to the evaporative ponds used in Chile and other South American countries to dry salt-rich water, or the hard-rock mining common in Western Australia, home to some of the world’s biggest lithium mines.

But what would have appealed to Rinehart and Hancock is the potential cost advantage of the Vulcan project with the company claiming that its lithium hydroxide will cost $3,142 per ton versus $6,855/t for hard rock lithium and $5872/t for evaporative brine processing.

Nearby Vehicle Makers

Another potential advantage is that the Rhine Valley location is close to some of the world’s biggest vehicle and battery-making factories.

Vulcan’s novel lithium production plan has been launched just as other lithium producers move to restart projects mothballed after the price of lithium crashed three years ago.

Albemarle Corporation, which controls a number of lithium projects in South America and Australia, is in the process of raising $1.3 billion in fresh capital to meet fast-growing demand from battery makers.

Australian hard rock lithium production. Photographer: Carla Gottgens/Bloomberg

© 2017 Bloomberg Finance LP

Over the past two months, the price of lithium has risen by 40% to around $10,000/t when sold as lithium carbonate, the most commonly traded form of the metal, though it is still well short of the boom-time price of $26,000/t reached in the first flush of the battery rush in late 2017.

Vulcan shareholders, including Rinehart and others who participated in the recent capital raising, have made handsome gains.

New shares issued through the capital raising have risen by 38% in less than a week from the issue price of $5 ($6.50) on February 2 to closing trades on the Australian stock market today at $6.90 ($A9).

Three months ago, Vulcan shares were trading at 80 cents ($A1.03).

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/6020f2d822e2828c5d2d90d8/0x0.jpg)