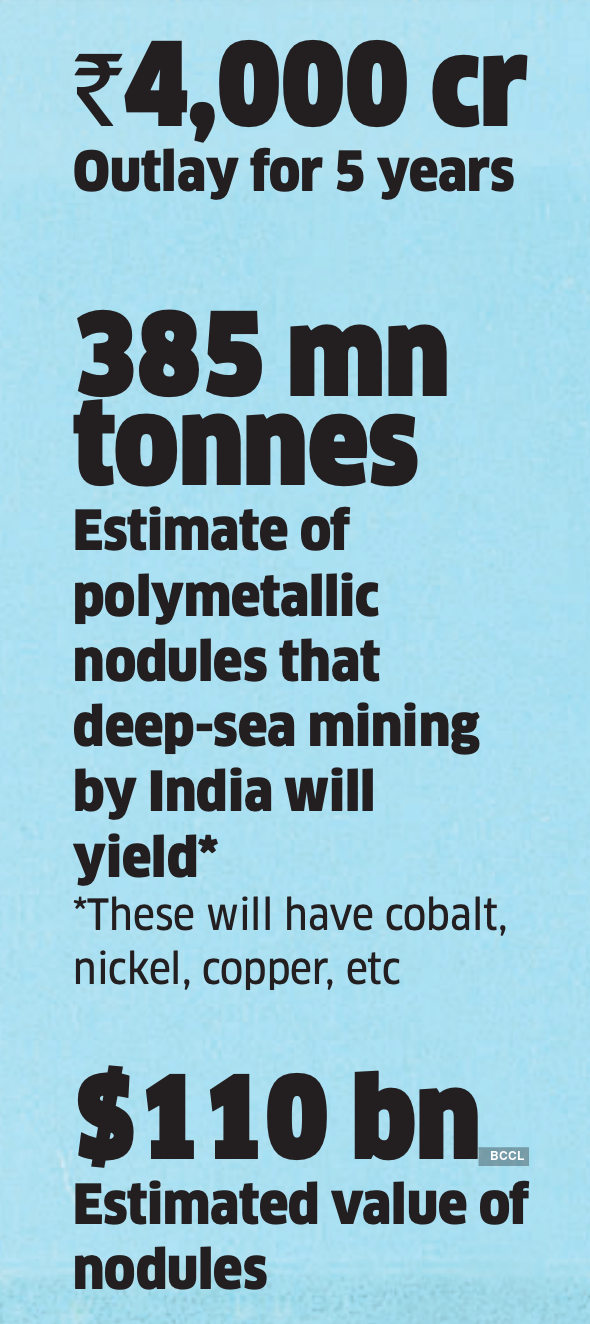

The development and launch of Matsya 6000 is part of India’s ambitious Deep Ocean Mission, for which Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has announced Rs 4,000 crore, to be spent over five years, in Budget 2021-22. While plans for the mission have been discussed over the last few years and work has begun, this is the first time there is a dedicated budget for it. “It’s been in the works for two-three years but this has now become a huge project in mission mode. The ocean has a lot of resources, both living and non-living, which we really need to map and exploit — for minerals, for energy, for drinking water,” says Madhavan Nair Rajeevan, secretary of the Ministry of Earth Sciences, which will be spearheading the mission.

The imperative to double down on deep sea exploration and research also stems from the fact that countries that are developing the technology for going 6,000 m down to exploit deep-sea minerals (currently not allowed commercially) will not part with their expertise because of its strategic importance. “Minerals mean money, so ocean technology is not easily shared.

Unless we do it ourselves, we cannot perfect this technology,” says Rajeevan. Even in manned submersibles, only five countries have been successful. Last November, China shared footage of its manned submersible, Striver, which descended over 10,000 m to the bottom of the Mariana Trench with three researchers. India’s manned submersible is being developed by the National Institute of Ocean Technology (NIOT), Chennai, with ISRO working on the “crew module”. It is expected to be ready by 2024. “We are halfway through and might venture into a 500 m depth next year,” says GA Ramadass, director, NIOT.

The submersible is one of the many projects of the Deep Ocean Mission, which involves institutes like NIOT, CSIR, ISRO and DRDO. Its other projects include developing deep-sea technologies and systems, deep-ocean exploration and setting up a research facility in Goa for marine biology and engineering. “It is an ambitious programme to develop deep-sea mining systems as it will have to bear the high pressure at depths of 4,000-6,000 m, where the resources are located. These mining systems are not available anywhere in the world,” says MP Wakdikar, senior scientist and adviser, Earth Sciences Ministry.

India has a 15-year contract with the International Seabed Authority (ISA), a UN backed body in charge of regulations for ocean floors, to explore 75,000 sq km in the Indian Ocean for manganese nodules, or polymetallic nodules, as they are known. These potatoshaped nodules, found on the seabed, are rich in copper, nickel, cobalt and manganese — metals which have a host of applications in devices, from batteries to mobile phones. An estimate by India from the surface pegs the quantity of these nodules at 385 million tonnes, with the processed minerals valued at $110 billion. The country also has a 15-year contract for the exploration of hydrothermal sulphides across 10,000 sq km southeast of Madagascar. “Hydrothermal sulphides are like underwater volcanos, in which heavy minerals are deposited, including rare earth elements like gold and platinum,” says Wakdikar.

Mission Mode

Deep Ocean Mission includes:

– Developing systems for deepsea mining, launching a manned submersible

– Deep-ocean exploration, including purchase of a vessel for this

-Deep-ocean biodiversity studies, bio prospecting

– Establishing a research facility in Goa for marine biology and engineering

– Undertaking climate change surveys of seas around India

-Making ocean thermal energy conservation efficacious*

– *Generates power from the difference in temperatures on the surface of the sea and its depths

While the surveys of polymetallic nodules have been complete to a large extent and the development of technology for exploratory mining has begun, surveys of hydrothermal sulphides are still at an exploratory stage, says Ramadass. Under the Deep Ocean Mission, there are plans to acquire a dedicated vessel for this exploration, which could cost around Rs 900 crore, depending on the equipment. There are about 30 private and government contracts with the ISA for deep-sea exploration but mining is not allowed because the international code for it has yet to be announced. The plan to allow deep-sea mining has also come under criticism from environmental organisations that fear it might cause irreparable damage to the flora and fauna on ocean floor. Ramadass says they will have to prove that even exploratory mining won’t harm the environment.

Mission Mode

The Deep Ocean Mission will also be examining the effect of climate change and warming on regional sea levels and assessing what impact that would have on coastal regions, which will be led by the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services. “It’s important that we do these climate change assessments now. Otherwise, we will not understand the local impact,” says director Srinivasa Kumar. Another project involves finding out if a pioneering effort by NIOT in setting up eco-friendly desalination plants in Lakshadweep — powered by using the difference in temperatures between the surface of the ocean and its depths — can be replicated in a coastal city like Chennai. “The plants use very little power and cause no pollution. But the challenge is that to reach 1,000 m depth from Chennai, you need to go very far from the coast, unlike on islands,” says Ramadass. Despite the daunting prospects, scientists working on the mission feel that India, surrounded by ocean on three sides, needs to develop technologies to explore it. “It’s tough. But unless we jump into the pool, how will we learn swimming? Similarly, unless we start going down (into the ocean), we can’t learn all these things,” says Rajeevan.