Trombone Shorty performs at the Electric Forest Music Festival. June 2013 in Rothbury, Michigan

Since the age of 4, Troy Andrews, better known in his guise as Trombone Shorty, has been playing the trombone at home in the city of New Orleans.

Since the early 90s, he’s performed annually at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival, often as a guest each year during renowned main stage closing sets by The Neville Brothers, taking over as closing act himself since 2013.

As the birthplace of jazz, New Orleans’ musical history is unparalleled. But it suffered a major blow on April 1, 2020 when teacher and legendary jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, father of musicians Branford and Wynton, passed away due to complications from COVID-19.

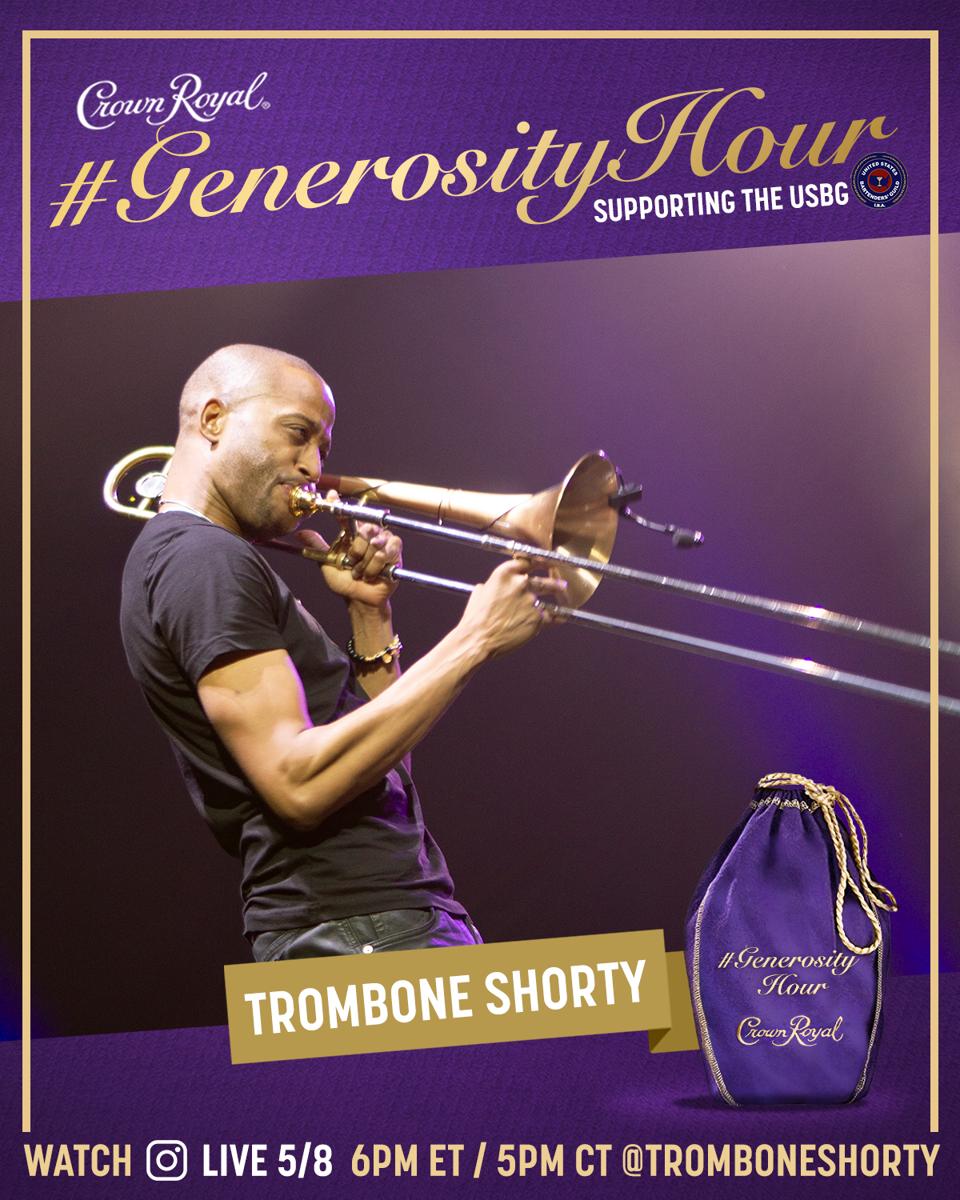

Later today, Andrews will raise a whisky toast to start the weekend, partnering with Crown Royal to perform at 6 PM EST during the weekly #GenerosityHour happy hour, streaming via Instagram Live at @TromboneShorty.

Just as artists have been particularly hard hit by the inability to tour amidst the coronavirus pandemic, so to have bartenders, who were amongst the first workers displaced as shelter-in-place orders went into effect and retail shutdowns began.

Today’s #GenerosityHour benefits bartenders via the USBG Bartender Emergency Assistance Fund and Crown Royal is donating $1 (up to $400,000) for every post containing the hashtag #GenerosityHour.

I spoke with Trombone Shorty about partnering with Crown Royal on today’s #GenerosityHour, the philanthropic efforts of his Trombone Shorty Foundation, the role of non-profit FM radio station WWOZ in bringing the city of New Orleans together during the pandemic and more. A transcript of our phone conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity, follows below…

I’m assuming you are hunkered down in New Orleans…

Trombone Shorty: I am. I’m hunkered down at the house. It’s the longest I’ve been home in about sixteen years.

Well, you’re starting the weekend by raising a glass of whisky with Crown Royal and playing on Instagram Live this afternoon as part of their weekly #GenerosityHour. How did this come together?

TS: Crown Royal reached out to me and, in this particular case, I think that we share the same values: helping and being generous to people. I spend a lot of my time giving back to communities and musicians. So when they presented this idea to help out the bartenders, it just struck home. These are people that do a job promoting and helping them out every day when they’re at work.

I have a lot of friends and family that are bartenders. It was near and dear to my heart and I had to be a part of the #GenerosityHour so we can help that industry out.

Trombone Shorty takes part in Crown Royal’s #GenerosityHour, to benefit the USBG Bartender Emergency … [+]

I was very sorry to read last month of the passing of Ellis Marsalis. I’m assuming as musicians in New Orleans you guys had some level of familiarity with one another. What kind of role did he play as patriarch of that family when it comes to music in New Orleans and did his passing make it even more important for you to get involved with this cause at this moment?

TS: Absolutely. Ellis Marsalis was a great teacher for many generations. I actually was never taught by him but I played shows with him – so I was taught on the stage whenever we would perform together.

There’s a long list of great musicians from, of course, his sons to Harry Connick, Nicholas Payton. Jon Batiste. There’s a bunch of people that went through that school. He was just a staple of our music and, more importantly, an educator that passed along a lot of knowledge up until he passed away.

It’s a great loss but he left so much knowledge that it will be passed on through his students.

Obviously, there’s an inability for artists to tour right now. And I think of all of the people that winds up impacting – whether it’s the bartenders at the venues, the crew members on the road or the artists themselves. In this era where it’s become so difficult for artists to monetize recorded music, just how important has touring become economically for artists as we enter a period where we don’t know when that ability to tour will return?

TS: Normally, I’ll tour and do at least 200 shows a year. I was looking very forward, like my fans and everyone else, to touring and being out there bringing music to people.

I’ve been touring nonstop since at least 2005 – literally nonstop. That’s been at least 90% of the revenue for me. And even if you pay attention to artists that are bigger, because the record industry has changed, you see that bigger artists have to tour year-round too. Because that’s the way to get directly to your audience and make a living. So, it’s very, very crucial to be able to tour. And I don’t know when that’s going to happen again.

It’s crucial for us to tour. That’s the driving point for musicians in this profession right now, be it rappers, instrumentalists or any other type of musician. That’s our main revenue and that’s what keeps us alive.

Trombone Shorty performs at the Electric Forest Music Festival. June 2013 in Rothbury, MI

The honor of closing out the main stage at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival has been bestowed upon you now since 2013. Unfortunately, that won’t be happening this year but what does that opportunity mean to you?

TS: To me, it’s the biggest honor that I can receive. Growing up in New Orleans, I’ve played since either 1990 or 1991.

When I was just a small kid, I played in the parade segment of it with my family band. When I was about 12, Cyril Neville of The Neville Brothers would bring me up every year to play a song or two with The Neville Brothers. And it was always a dream for me to either join The Neville Brothers band or be in a position to close out the Jazz Fest – not necessarily take over their spot but just to be able to close it out.

That’s a major milestone for me in my career. Because, to me, as a musician growing up here, that’s about the biggest stage we can possibly be on. Not only do I get to play in front of all of the people that have watched me grow up playing music in the city, but also all of the people that fly in from all over the world to see me perform in my hometown. There’s a collective of people from all over the world.

Just to see some of my family members in the crowd or some superfans that I see when we play in say New York – to have all of those people come into our gumbo pot of New Orleans and for me to be able to perform in front of them? That’s the biggest honor for me.

And to be able take over for The Neville Brothers, who raised me musically… Cyril Neville, I used to practically live at his house. To be able to do that is just unimaginable and unbelievable – even the feeling I get just talking about it.

Last year, I had the honor of having some of the Nevilles play on the stage with me – as I did with them for so many years. That was another milestone just to bring them on stage with me and perform in front of the city.

I read that you were recently listening to a rebroadcast of The Neville Brothers’ 1994 performance at Jazz Fest on WWOZ. What’s it like being able to revisit that and what role does WWOZ play in New Orleans in terms of bringing people together at a time like this?

TS: For me, it wasn’t revisiting it – because I didn’t know who they were in 1994. So it was a discovery for me. It was my first time ever hearing that set. WWOZ put together the cues as they would do when Jazz Fest was actually taking place.

I used to be able to just go into WWOZ with my band and just play. We wouldn’t know who was on the air or who was the DJ on during that time. We’d just set up our instruments and say, “Hey, we’re here to play. We’re not really promoting anything, we don’t have a CD that we’re trying to sell or anything. We just happened to be in the neighborhood.” It’s just a family community atmosphere over there.

And it plays a big role in our city. Because a lot of local musicians, that’s probably the only place that they ever got their music heard on the airwaves. So, it’s very important that we support that and continue to keep them alive. Because that’s a platform that a lot of people can have their music played even if they don’t get a chance to be played on other radio stations around the world.

And being able to revisit that Neville Brothers set, I was very excited to hear it and I instantly turned into a student. I’m trying to reach out to WWOZ and the Jazz Fest archives to see if I can get that actual recording – because there’s some things that I want to borrow from that show and implement into mine.

NEW ORLEANS, LOUISIANA – MAY 05: Trombone Shorty of Trombone Shorty & Orleans Avenue (L) and Cyril … [+]

There’s a few living room performance videos on your Facebook page and there’s the Crown Royal #GenerosityHour appearance coming up later today at 6 PM EST on Instagram Live. In terms of continuing to bring music to people, how important is that connection right now?

TS: I think it’s very important that we bring music to people any type of way we can. Because music can take us into a different head space and bring us to happy times – fond moments that we remember in life.

For me to be able to reach a percentage of my audience online and just give them a little something, it’s very important. I think a lot of people need it and they’re looking forward to it – just as I look forward to other musicians singing online. Any type of way we can bring smiles to people’s faces, that’s what we’re here to do.

I just want to encourage people to comment with the hashtag #GenerosityHour. Because the more hashtags that we get like that, the more we can help out the bartending community.

Also, with my Trombone Shorty Foundation, after this event, we’ll be planning to help out the local musicians in some way. So with the #GenerosityHour and my Foundation, we all share the same vision and the same industry of people that keep it alive.

I’m just honored to partner with these guys to make that happen for people that we might not necessarily think about. When we hear that a bar is closing, we think of the building – and maybe people think about the bartenders. But these are people that are the heart and soul of these buildings that we play in and I think it’s only right that we help them out as much as we can – as they do for musicians.

We’re all in this together. If we never understood that before, this situation has put that into perspective for us. We need to do the best we can to help each other.

/https://specials-images.forbesimg.com/imageserve/5eb486df02fb3a000628fbaa/0x0.jpg)