From a secure room about 1,200 kilometers (745 miles) from the epicenter, Xi expressed his condolences to those who have died in the outbreak. He urged greater public communication, as around the world concerns mounted about the potential threat posed by the new disease.

That same day, Chinese authorities reported 2,478 new confirmed cases — raising the total global number to more than 40,000, with fewer than 400 cases occurring outside of mainland China. Yet CNN can now reveal how official documents circulated internally show that this was only part of the picture.

In a report marked “internal document, please keep confidential,” local health authorities in the province of Hubei, where the virus was first detected, list a total of 5,918 newly detected cases on February 10, more than double the official public number of confirmed cases, breaking down the total into a variety of subcategories. This larger figure was never fully revealed at that time, as China’s accounting system seemed, in the tumult of the early weeks of the pandemic, to downplay the severity of the outbreak.

The previously undisclosed figure is among a string of revelations contained within 117 pages of leaked documents from the Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, shared with and verified by CNN.

Taken together, the documents amount to the most significant leak from inside China since the beginning of the pandemic and provide the first clear window into what local authorities knew internally and when.

The Chinese government has steadfastly rejected accusations made by the United States and other Western governments that it deliberately concealed information relating to the virus, maintaining that it has been upfront since the beginning of the outbreak. However, though the documents provide no evidence of a deliberate attempt to obfuscate findings, they do reveal numerous inconsistencies in what authorities believed to be happening and what was revealed to the public.

The documents, which cover an incomplete period between October 2019 and April this year, reveal what appears to be an inflexible health care system constrained by top-down bureaucracy and rigid procedures that were ill-equipped to deal with the emerging crisis. At several critical moments in the early phase of the pandemic, the documents show evidence of clear missteps and point to a pattern of institutional failings.

One of the more striking data points concerns the slowness with which local Covid-19 patients were diagnosed. Even as authorities in Hubei presented their handling of the initial outbreak to the public as efficient and transparent, the documents show that local health officials were reliant on flawed testing and reporting mechanisms. A report in the documents from early March says the average time between the onset of symptoms to confirmed diagnosis was 23.3 days, which experts have told CNN would have significantly hampered steps to both monitor and combat the disease.

China has staunchly defended its handling of the outbreak. At a news conference on June 7, China’s State Council released a White Paper saying the Chinese government had always published information related to the epidemic in a “timely, open and transparent fashion.”

“While making an all-out effort to contain the virus, China has also acted with a keen sense of responsibility to humanity, its people, posterity, and the international community. It has provided information on Covid-19 in a thoroughly professional and efficient way. It has released authoritative and detailed information as early as possible on a regular basis, thus effectively responding to public concern and building public consensus,” says the White Paper.

CNN has reached out to China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and National Health Commission, as well as Hubei’s Health Commission, which oversees the provincial CDC, for comment on the findings disclosed in the documents, but received no response.

Health experts said the documents laid bare why what China knew in the early months mattered.

“It was clear they did make mistakes — and not just mistakes that happen when you’re dealing with a novel virus — also bureaucratic and politically-motivated errors in how they handled it,” said Yanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, who has written extensively on public health in China. “These had global consequences. You can never guarantee 100% transparency. It’s not just about any intentional cover-up, you are also constrained with by technology and other issues with a novel virus. But even if they had been 100% transparent, that would not stop the Trump administration downplaying the seriousness of it. It would probably not have stopped this developing into a pandemic.”

Tuesday, December 1, marks one year since the first known patient showed symptoms of the disease in the Hubei provincial capital of Wuhan, according to a key study in the Lancet medical journal.

At the same time that the virus is believed to have first emerged, the documents show another health crisis was unfolding: Hubei was dealing with a significant influenza outbreak. It caused cases to rise to 20 times the level recorded the previous year, the documents show, placing enormous levels of additional stress on an already stretched health care system.

The influenza “epidemic,” as officials noted in the document, was not only present in Wuhan in December, but was greatest in the neighboring cities of Yichang and Xianning. It remains unclear what impact or connection the influenza spike had on the Covid-19 outbreak. And while there is no suggestion in the documents the two parallel crises are linked, information regarding the magnitude of Hubei’s influenza spike has still yet to be made public.

The leaked revelations come as pressure builds from the US and the European Union on China to fully cooperate with a World Health Organization inquiry into the origins of the virus that has since spread to every corner of the globe, infecting more than 60 million people and killing 1.46 million.

But, so far, access for international experts to hospital medial records and raw data in Hubei has been limited, with the WHO saying last week they had “reassurances from our Chinese government colleagues that a trip to the field” would be granted as part of their investigation.

The files were presented to CNN by a whistleblower who requested anonymity. They said they worked inside the Chinese healthcare system, and were a patriot motivated to expose a truth that had been censored, and honor colleagues who had also spoken out. It is unclear how the documents were obtained or why specific papers were selected.

The documents have been verified by six independent experts who examined the veracity of their content on behalf of CNN. One expert with close ties to China reported seeing some of the reports during confidential research earlier this year. A European security official with knowledge of Chinese internal documents and procedures also confirmed to CNN that the files were genuine.

Metadata from the files seen by CNN contains the names of serving CDC officials as modifiers and authors. The metadata creation dates align with the content of the documents. Digital forensic analysis was also performed to test their computer code against their purported origins.

Sarah Morris, from the Digital Forensics Unit at Britain’s Cranfield University, said there was no evidence the data had been tampered with or was misleading. She added the older files looked like they had been used repeatedly over a long period of time. “It’s almost like a mini file system,” she said. “So, it’s got lots of room for deleted stuff, for old things. That’s a really good sign [of authenticity].”

World got more optimistic data than reality

The documents show a wide-range of data on two specific days, February 10 and March 7, that is often at odds with what officials said publicly at the time. This discrepancy was likely due to a combination of a highly dysfunctional reporting system and a recurrent instinct to suppress bad news, said analysts. These documents show the full extent of what officials knew, but chose not to spell out to the public.

On February 10, when China reported 2,478 new confirmed cases nationwide, the documents show Hubei actually circulated a different total of 5,918 newly reported cases. The internal number is divided into subcategories, providing an insight into the full scope of Hubei’s diagnosis methodology at the time.

“Confirmed cases” number 2,345, “clinically diagnosed cases” 1,772, and “suspected cases” 1,796.

The strict and limiting criteria led ultimately to misleading figures, said analysts. “A lot of the suspected cases there should have been included with the confirmed cases,” said Huang, from the Council on Foreign Relations, who reviewed the documents and found them to be authentic.

“The numbers they were giving out were conservative, and this reflects how confusing, complex and chaotic the situation was,” he added.

That month, Hubei officials presented a daily number of “confirmed cases,” and then included later in their statements “suspected cases,” without specifying the number of seriously ill patients who had been diagnosed by doctors as being “clinically diagnosed.” Often in nationwide tolls, officials would give the daily new “confirmed” cases, and provide a running tally for the entire pandemic of “suspected cases,” also into which it seems the “clinically diagnosed” were added. This use of a broad “suspected case” tally effectively downplayed the severity of patients who doctors had seen and determined were infected, according to stringent criteria, experts said.

William Schaffner, professor of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University, said the Chinese approach was conservative, and the data “would have been presented in a different way had US epidemiologists been there to assist.”

He said Chinese officials “seemed actually to minimize the impact of the epidemic at any moment in time. To include patients who were suspected of having the infection obviously would have expanded the size of outbreak and would have given, I think, a truer appreciation of the nature of the infection and its size.”

Protocols for coronavirus diagnosis, published by China’s National Health Commission in late January, told doctors to label a case “suspected” if a patient had contact history with known cases, and a fever and pneumonia symptoms, and to elevate the case to “clinically diagnosed” if those symptoms were confirmed by an X-ray or CT scan. A case would only be “confirmed” if polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or genetic sequencing tests came back positive.

Andrew Mertha, director of the China Studies Program at John Hopkins University, said officials might have been motivated to “lowball” numbers to disguise under-funding and preparedness issues in local health care bodies like the provincial CDC.

According to Mertha, the documents, which he reviewed and considered authentic, seemed to be organized so as to allow senior officials to paint whatever picture they wished.

“You are giving them all the options there without putting somebody in an explicitly embarrassing position — giving them both the anvil or the life-raft to then choose from.”

Chinese officials did soon improve the reporting system, placing the “clinically diagnosed” cases into the “confirmed” category by mid-February. Top health and provincial officials in Hubei were also removed from their positions at that time, who would have been ultimately responsible for the reporting. Furthermore, wider and improved testing meant “suspected” cases could be clarified quicker and featured less in reporting. Separately, China’s diagnostic criteria have been criticized by health experts for their continued, public decision to not count asymptomatic cases.

Death tolls listed in the documents reveal the starkest discrepancies. On March 7, the total death toll in Hubei since the beginning of the outbreak stood at 2,986, but in the internal report it is listed as 3,456, including 2,675 confirmed deaths, 647 “clinically diagnosed” deaths, and 126 “suspected” case deaths.

Dali Yang, who has extensively studied the outbreak’s origins, said that in February numbers “still mattered because of global perceptions.”

“They were still hoping it was like 2003, and like Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) would be eventually contained, and everything can go back to normal,” added Yang, who is a professor of political science at the University of Chicago. He pointed to the February 7 call between presidents Trump and Xi. “I think that’s also the (wishful) impression that Trump got — that this is going to disappear.”

The documents, however, are by no means clear cut. On two occasions, the public death numbers are narrowly over reported, with the internal figures indicating single-digit discrepancies of five and one, respectively.

On other occasions, the data provides glimpses of new information but without vital context. Even though China has never revealed the total number of Covid-19 cases in 2019, a graph in one document appears to suggest a much higher number had been detected. In the bottom left hand column of the graph marked 2019 the number of “confirmed cases” and “clinically diagnosed” cases appears to reach around 200 altogether. The documents do not elaborate further. To date, the clearest indication of how many cases were detected in 2019 is the 44 “cases of pneumonia of unknown etiology (unknown cause)” that Chinese authorities reported to the WHO for the period of the pandemic up to January 3, 2020.

Long wait time for tests

Testing was inaccurate from the start, the documents said, and led to a reporting system with weeks long delays in diagnosing new cases. Experts said that meant most of the daily figures that informed the government response risked being inaccurate or dated.

On January 10, one of the documents reveals how during an audit of testing facilities, officials reported that the SARS testing kits that were being used to diagnose the new virus were ineffective, regularly giving false negatives. It also indicated that poor levels of personal protective equipment meant that virus samples had to be made inactive before testing.

The high false-negative rate exposed a series of problems China would take weeks to rectify. According to reports in Chinese state media in early February, Hubei health experts had expressed frustration with the accuracy of nucleic acid tests. Nucleic acid tests work by detecting the virus’ genetic code, and were thought to be more effective at detecting the infection, particularly in the early stages.

However, the tests carried out at that time resulted in only a 30% to 50% positive rate, among already confirmed cases, according to officials quoted in state media. In order to avoid “false negative” results, health officials began to test suspected cases repeatedly.

By early February, laboratories in Hubei had capacity to test more than 10,000 people a day, according to state media reports. To cope with the high volume, officials decided to begin incorporating other clinical diagnosis methods, such as CT scans. This led to the creation of category referred to internally as “clinically diagnosed cases.” It was not until mid-February that the clinically diagnosed cases were added to the confirmed case numbers.

Other, yet graver issues noted in the documents were raised by health experts.

In the first months of the outbreak, the average time required to process a case — from the patient experiencing symptoms (onset) to being confirmed diagnosed was 23.3 days.

The persistent delay would likely have made it much harder to direct public health interventions, said Dr. Amesh Adalja, at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

“You’re looking at data that’s three weeks old and trying to make a decision for today,” he said.

The report notes that, by March 7, the system had much improved, with over 80% of the new confirmed cases diagnosed that day being recorded in the system that same day.

Multiple experts described the time lag as extraordinary, even when factoring in the initial difficulties faced by authorities.

“That adds another layer of understanding as to why some of the numbers that came out from the higher levels of government probably were off,” said Schaffner from Vanderbilt University. “In the United States, Britain, France and Germany, there’s always a lag. You don’t know instantaneously. But 23 days is a long time.”

Early warning system hampered

A lack of preparedness is reflected throughout the documents, sections of which are highly critical in their internal assessment of the government’s support for the Center for Disease Control and Prevention operations in Hubei.

The report characterizes the Hubei CDC as underfunded, lacking the right testing equipment, and with unmotivated staff who were often felt ignored in China’s vast bureaucracy.

The documents include an internal audit, which forensic analysis shows was written in October 2019, before the pandemic began.

More than a month before the first cases are believed to have emerged, the review continues to urge the health authorities to “rigorously find the weak link in the work of disease control, actively analyze and make up for the shortcomings.”

The CDC internal report complains over an absence of operational funding from the Hubei provincial government and notes the staffing budget is 29% short of its annual target.

After the outbreak, Chinese officials swiftly moved to assess the problems. Yet more than four months after the virus was first identified, major issues continued to hamper disease control efforts in key areas, the documents show.

The report also highlights the CDC’s peripheral role in investigating the initial outbreak, noting that staff were constrained by official processes and their expertise not fully utilized. Rather than taking a lead, the report suggests CDC staff were resigned to “passively” completing the task issued by superiors.

Officials were also faced with a lumbering and unresponsive IT network, known as the China Infectious Disease Direct Reporting System, according to state media, installed at cost of $167 million after the 2003 SARS outbreak.

Theoretically, the system was supposed to enable regional hospitals and CDCs to directly report infectious diseases to a centrally managed system. This would then allow the data to be shared instantly with CDCs and relevant health departments nationwide. In reality, it was slow to log into, one audit said, and many other bureaucratic procedural restrictions hampered rapid data recording and gathering.

According to Huang, from the Council on Foreign Relations, the report belies China’s claim to have massively invested in disease control and prevention after the 2003 SARS outbreak.

“If you look at the local level, the picture is not as rosy as the government had claimed,” he said.

Large outbreak of flu in Hubei

The documents also reveal a previously undisclosed a 20-fold spike in influenza cases recorded in one week in early December in Hubei province.

The spike, which occurred in the week beginning December 2, saw cases rise by approximately 2,059% compared to the same week the year before, according to the internal data.

Notably, the outbreak that week is not felt most severely in Wuhan — the epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak — but in the nearby cities of Yichang, with 6,135 cases, and Xianning, with 2,148 cases. Wuhan was the third worst hit with 2,032 new cases that week.

Public data shows a nationwide spike in influenza in December. Experts, however, note the rise in influenza cases, while not unique to Hubei, would have complicated the task of officials on the lookout for new dangerous viruses.

Though the magnitude of the Hubei flu spike has not been previously reported, it is difficult to draw any hard conclusions, especially in regard to the potential prevalence of previously undetected Covid-19.

The documents show that testing carried out on the influenza patients return a high number of unknown results. However, experts cautioned that this did not necessarily indicate that the unknown test results were in fact undetected coronavirus cases.

“They’re only testing for what they know — this [coronavirus] is an unknown unknown,” said Adalja, the JHU academic, adding that such a scenario that was not uncommon, globally.

“We’re just not that great at diagnosing them. We look for the usual suspects. We’re always looking for the horses, but never the zebras.”

The Wuhan CDC later conducted retrospective research into influenza cases dated as early as October 2019 in two Wuhan hospitals, in an attempt to look for traces of coronavirus. But, according to a study published in the journal Nature, they were unable to detect samples of the virus dating back earlier than January 2020. Similar studies have yet to be carried out in other Hubei cities.

Separately, the flu spike could have helped to unintentionally accelerate the coronavirus’ early spread, said Huang.

“Those people were seeking care in hospitals, increasing the chances of COVID infection there,” he said.

The influenza data also points to the influenza outbreak being worst in Yichang. While the influenza spike and the emergence of Covid-19 are not linked in the documents or by other evidence, data pinpointing a flu-like outbreak in multiple cities in Hubei will likely be of interest to those researching the origins of the disease.

The Chinese government has previously pointed to the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan as the likely initial epicenter of the outbreak in mid-December, where meat of exotic wild animals was sold. Yet that claim has been at least partially challenged by a Lancet study of the first December patients, which determined one third of the 41 infected that month had no direct connection to that market.

Yichang, 320 kilometers (198 miles) west of Wuhan, was hit hardest by the influenza outbreak — almost three times as many as Wuhan in the same week beginning December 2.

Mertha, the China expert from JHU, said the spike in Yichang, while not connected to Covid-19 in the documents, could nonetheless open up new theories about where the virus began.

“The order of magnitude of change means there has to be something going on,” he said.

An unfolding crisis

China’s leaders were the first to confront the virus, implementing a raft of draconian restrictions beginning in late January intended to curb the spread of the outbreak. Using sophisticated surveillance tools, government officials enforced strict lockdowns across the country, largely restricting more than 700 million people to their homes, while sealing national borders and carrying out widespread testing and contract tracing.

According to a study published in the journal Science in May, the stringent measures adopted during those first 50 days of the pandemic likely helped break the localized chain of transmission.

Today, China is close to zero local cases and although small-scale outbreaks continue to flare, the virus is mostly contained.

In February, however, it was a different story. As case numbers soared nationwide, government officials were facing a potential crisis of legitimacy, with public opinion fast turning against the ruling Communist Party over its perceived mishandling of the deadly new disease.

During the last 30 years, analysts say, many in China have appeared willing to relinquish political freedoms in return for increased material wealth, social stability and greater opportunities.

The virus fundamentally threatened that social contract — putting hundreds of millions at risk while damaging an economy already weakened by an ongoing US-China trade war. In late January, Xi, China’s most powerful leader in decades, publicly ordered “all-out efforts” to contain the virus’ spread.

At the time, China was celebrating the Lunar New Year holiday, its most important annual holiday. The notion of an impending pandemic seemed to many like an abstract distraction, as people returned home to spend time with their families.

Xi’s highly public intervention, which came just days after Wuhan was placed under lockdown, carried with it a clear message: Failure is not an option.

Throughout this period, the gulf between public statements by Chinese officials and the internally distributed data is at times blunt. The leaked documents show the daily confirmed death toll in Hubei rose to 196 on February 17. That same day, Hubei publicly reported just 93 virus deaths.

Another report also records the deaths of six health care workers from Covid-19 by February 10. Their deaths were not public at the time, and were highly sensitive, given the volume of sympathy over-worked health care staff, on the frontline of the pandemic, were getting on social media at the time.

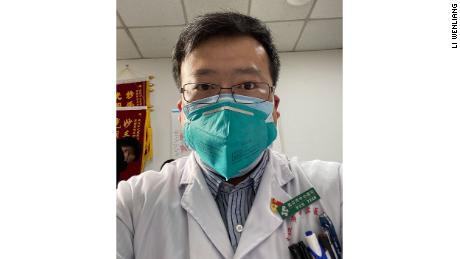

As the virus spread, local officials were accused of downplaying the outbreak and its risk to the public. In late December, a young doctor named Li Wenliang in one of Wuhan’s main hospitals, was among other medical workers summoned by local authorities and later received formal “reprimand” from the police for attempting to raise the alarm about a potential “SARS-like” virus. State media reported their punishment and warned public against rumour mongering.

Li, 34, later contracted the disease. His condition quickly worsened and in the early morning of February 7 he died, resulting in almost unprecedented levels of anger and outrage across mainland China’s heavily censored internet.

It is not clear to what extent the central government was aware of the actions taking place in Hubei at that time, or how much information was being shared and with whom. The documents offer no indication that authorities in Beijing were directing the local decision-making process.

However, Mertha, the JHU academic, said the mismatch between the higher internal and lower public figures on the February death toll “appeared to be a deception, for unsurprising reasons.”

“China had an image to protect internationally, and lower-ranking officials had a clear incentive to under-report — or to show their superiors that they were under-reporting — to outside eyes,” he said.

Conversely, however, the leaked documents also provide something of a defense of China’s overall handling of the virus. The reports show that in the early stages of the pandemic, China faced the same problems of accounting, testing, and diagnosis that still haunt many Western democracies even now — issues compounded by Hubei encountering an entirely new virus.

Similarly, no mention is made by officials of a so-called laboratory leak, or that the virus was man-made, as some critics, including top US officials, have claimed without evidence. There is one mention of sub-par facilities at a bacterial and toxic species preservation center, though the point is not elaborated on, nor is its significance made clear.

China and its healthcare workers were under immense strain as the outbreak took hold, said Yang, from the Council of Foreign Relations.

“They had a massive run on the medical system. They were overwhelmed. There was truly despair among medical professionals by the end of January, because they were extremely overworked and they were also enormously discouraged by the high number of deaths that were occurring with a disease they had not treated previously,” he added.

Hubei, which lags far behind Beijing, Shanghai and other major Chinese administrative divisions in terms of GDP per capita, was the first region to confront a virus that would go on to confound many of the world’s most powerful countries.

Schaffner, from Vanderbilt University, said many of the comments in the documents might have been made in the US, “where, over the past 15 to 20 years, at particularly the state and the local level, public health funding has become constrained.”

The documents show health care officials had no comprehension as to the magnitude of the impending disaster.

Nowhere in the files is it indicated that officials believed the virus would become a global pandemic.

Tuesday marks exactly 12 months since the first patient in Wuhan started showing symptoms, according to the Lancet study. The death toll and number of people infected by the virus, now known to the world as Covid-19 and impacting the lives across the planet, continues to grow, day on day.