While many modified their research to suit COVID-19, others started afresh to cater to the more pressing and immediate demand – beating the pandemic.

One year on, their efforts have paid off with Indian scientists at the forefront of the global fight against the disease despite the constraints of limited funding and available resources.

Even before the first case of the novel coronavirus was reported in India, Debojyoti Chakraborty, for instance, had anticipated that scientists had their work cut out and it was only a matter of time before the virus would cut a wide swathe across the country and leave no one unscathed.

In January, Chakraborty and his team at New Delhi’s CSIR-Institute of Genomics and Integrative Biology were working on a prototype for the diagnosis of sickle cell anaemia based on gene-editing technology CRISPR.

“Once the information about the pandemic came to light, we started reorienting our platform for the SARS-CoV-2 virus, gathering all the intelligence and reagents along the way,” Chakraborty told .

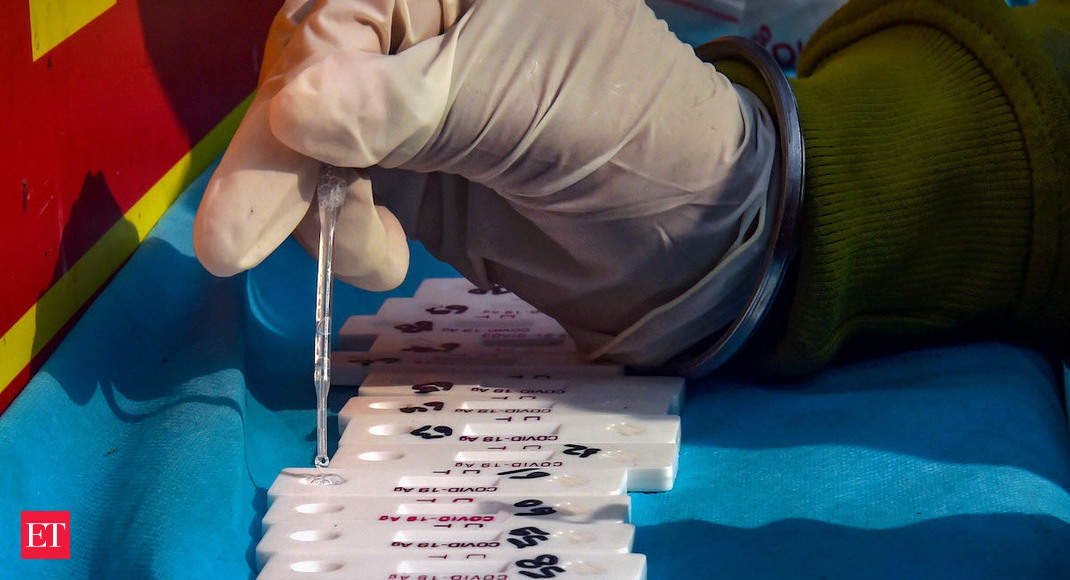

And so in January itself, the team started working on a CRISPR-based COVID-19 test — ‘FELUDA’ is billed as a cheaper, faster and simpler alternative to the standard RT-PCR diagnosis.

Named after Satyajit Ray’s famed detective, the test is priced at an affordable Rs 500 and can deliver a result in 45 minutes. It is able to differentiate SARS-CoV-2 from other coronaviruses even if genetic variations between them are minute.

The FELUDA test is just one of the several accomplishments. From developing computer models to predict the trajectory of the disease and creating diagnostics to designing masks and aiding vaccine research, India’s scientists have made remarkable contributions in multiple fields.

Like Chakraborty, Rajneesh Bhardwaj and Amit Agrawal from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Bombay were busy in their line of research — understanding the physics of evaporation of droplets for applications in spray cooling and inkjet printing and several other topical problems from the domain of thermal and fluid engineering.

However, as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, they turned their attention to applying their knowledge to understanding the evaporation of respiratory droplets on surfaces and the spread of cough clouds — the main cause of airborne transmission of the novel coronavirus.

“We were among the first scientists worldwide to start working on these scientifically and socially relevant problems. For example, the second paper and subsequently three more papers in the special issue on COVID in the prestigious journal Physics of Fluids came from our group,” Bhardwaj told .

“Our plans were to continue in the domain of thermal and fluid engineering. However, the pandemic came as an opportunity in our research plan. We thought of extending and applying our knowledge to several unanswered questions in the context of COVID,” Agrawal added.

The year saw several research groups in India trying to get to the root of COVID-19 by understanding the different aspects of the viral disease, including the way it spreads, the role of masks and developing diagnostic tests.

“The medical community has also reported clinical data and development of vaccines in an unprecedented way,” says Bhardwaj.

A special issue on “Technologies for fighting COVID-19” published in the journal Transactions of Indian National Academy of Engineering summarised these efforts and highlighted 49 accepted papers published by Indian researchers.

“It is a difficult task to develop new technologies within a short span but many of the existing technologies can be deployed with subtle changes to meet the immediate needs challenged by COVID-19,” the authors of the special issue said.

Before the pandemic struck, Murali Dharan Bashyam and his team at the Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics (CDFD), Hyderabad, were on the verge of completing two major projects — one on pancreatic cancer, and the other on colorectal cancer, a result of work done for more than 10 years.

“It was very disconcerting for my group when the lockdown was implemented. However, we realised that we needed to wait. By June 2020, we thought it was our duty to contribute to COVID-19 research,” the scientist told .

After intense discussions between researchers at several national institutions and the Department of Biotechnology, the government identified four major areas of COVID-19 research — viral genomics, diagnostics, therapeutics and vaccine development.

“My group decided to contribute in the area of viral genomics since that was our area of expertise,” Bashyam added.

The team’s work on evolutionary genomics of the viral strains infecting the Telangana state appeared in the preprint repository MedRxiv and is expected to be published in a peer reviewed journal soon.

“In addition, we are one of the three leading groups coordinating a pan-India viral genome sequence consortium,” he said.

The project was undertaken to sequence 1,000 SARS-CoV-2 genomes from samples to understand the evolving behaviour of the coronavirus.

There are several others devoting their knowhow, time and efforts towards understanding COVID-19, which has infected almost 80 million people globally with the US topping the list with 18.7 million cases and India number two with more than 10 million cases.

Gyaneshwar Chaubey deals with the phylogeny, or evolutionary history of various organisms in his routine work. In 2020, the Banaras Hindu University (BHU) zoologist had planned to map the Lakshadweep Islands, several Bangladeshi and many Northeast Indian populations.

“However, COVID-19 changed everything,” the scientist told .

Chaubey shifted his work towards analysing the mutations in the human gene responsible for the expression of the Angiotensin Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2), a protein on the surface of cells which is believed to act as a gateway for the novel coronavirus into the human body.

By October, his team published a paper which described a variation in a genetic mutation among Indians that may be the main reason behind the difference in the death rates due to COVID-19 across various states of the country.

“We were sure that ‘nature’ is so smart that whenever any such event happens, it doesn’t destroy the whole humanity. Because we are so diverse and diversity always provides immunity to some people against diseases,” Chaubey added.

Bashyam noted that Indian scientists have responded very well to the pandemic with cutting edge research in the four areas of research.

“Several national-level collaborations were established and the rapid and specific response from several national laboratories are now bearing fruit. This definitely has been one of the fastest and efficiently managed responses from Indian scientists,” he added.